Build a service, grow it, and worry about where the money’s coming from later. That seems to be the general monetization mantra of the internet age, with the likes of Twitter and Facebook initially focusing on building their userbase before they paid too much attention to how they’re going to make cash via advertising.

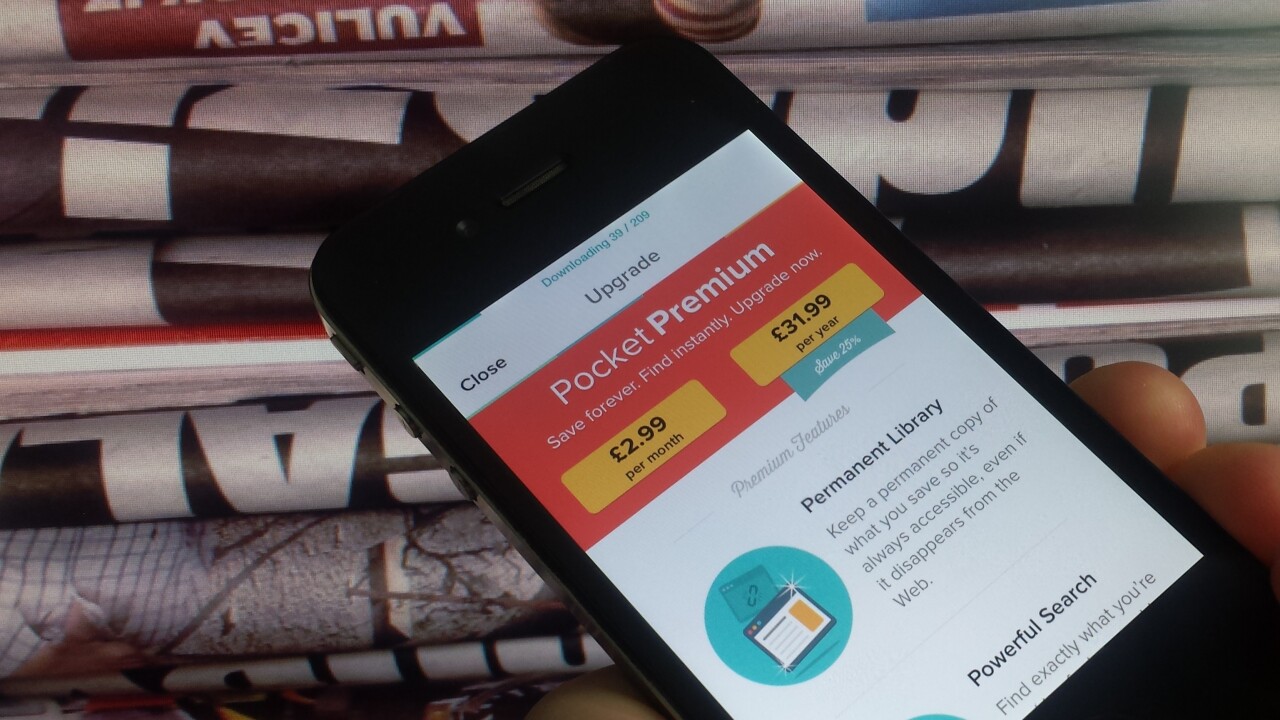

And just last week, Pocket introduced a new Premium subscription to its read-it-later service more than five years after launch, which the company said serves as its “first source of revenue”.

But how willing will people be to commit cash on a regular basis to access a few more features?

Freemium flaw

With so many people now expecting things for free, companies can have a torrid time finding ways to garner revenue without affecting the core experience. Freemium has really come to the fore in the digital age, whereby a core service is offered gratis, and value-added features are served up at a price. The system not only allows consumers to ‘suck-it-and-see’ before committing hard cash to the cause, but they can continue to enjoy a reduced-feature version for free, perhaps supported by adverts too.

However, when offering freemium, it’s important not to start chipping away at the basic free service to make the paid service more appealing. Spotify, arguably one of the internet’s biggest ‘freemium’ success stories, has tried this in the past.

Back in April 2011, before it had even launched in the US, we reported that Spotify was introducing more restrictions to its free Spotify Open service that would come into force once a user was registered for six months. The changes meant the free music playback was halved to ten hours each month, and some tracks could only be played a handful of times. These limits remained in place in many countries up until December last year, when Spotify finally removed all listening restrictions, saying: “More access means more engagement”. In other words, the longer someone has access to the full (ad-supported) service, the more likely they will be to pay to remove ads and gain access to the premium features.

But convincing lots of people to pay money for a non-physical service or product, irrespective of its inherent value, is still a hard thing to do. It’s something that many companies dedicate much time and resources to, from Dropbox and Evernote, through to Spotify and beyond – hugely popular services, with more-than-adequate free tiers.

Premium Pocket

Pocket is one of my favorite online services, and it was interesting to observe its attempts to monetize with a subscription model.

Thankfully, Pocket didn’t touch the existing free version at all, something that would no doubt have caused uproar amongst its 12 million-strong army of users. Instead, it introduced a handful of optional add-ons, including a ‘Permanent Library’, a feature that stores a copy of all the articles and Web pages you save permanently. There’s also a new search facility that lets you sift through your archives by text, topics, tags, authors and more, while suggested tags should help cut the time it takes to file an article in a specific category.

But for $4.99 a month, or $44.99 a year, will Pocket users really be willing to make a permanent financial commitment to the cause for these extra features? It’s not that the figure being asked for is a silly amount of money in itself, it’s just that considering the myriad of other monthly outgoings people have these days, from mobile phone contracts to digital newspapers and movie-streaming services, subscription fatigue is a real thing.

Bang for your buck

Let’s look at how much bang you get for your buck elsewhere. With Spotify, which costs double that of Pocket (per month), you get unlimited access to an arsenal of more than 20 million songs, ad-free, on just about any platform. Then there’s Netflix, where you can stream Breaking Bad and a ton of other awesome TV shows (and a few movies), which costs $7.99 a month for most people, though this recently increased by a dollar for new users.

Earlier this year Dollarbird, one of my favorite personal finance-trackers, launched for Android alongside a new Premium subscription model as it sought to monetize. It follows a pretty much identical model to that of Pocket in terms of pricing, and Dollarbird’s Premium features are significant enough to merit paying for in some capacity. But again, its downfall will likely be its subscription model.

Encouraging people to subscribe, and retaining them, is a tough task. Even for the the very best of online services. I’m just not convinced that subscriptions are the way to go for the vast majority of online firms – there has to be something truly exceptional on offer for it to work.

“It’s actually one of the hardest things in a freemium business (getting people to pay) – you’ve basically conditioned people to think that your product is free,” explained Sujay Jaswa, VP of Sales and Business development at Dropbox, at the FT’s Digital Media event in London earlier this year.

“I think the number one thing you have to do is create a value differentiation – people have to feel like they’re getting more in exchange for paying,” he continued. “If they feel like they’re really just paying for something that’s the free product, and they’re not really sure what they’re getting, or getting something that they don’t value, that’s where the problem kicks in. You really have to figure out where the value is for the customer, well beyond what their expectations have been determined by the free product.”

The extent of this problem will of course vary from product to product. For Dropbox, it has around 200 million users globally and what’s thought to be around a four percent paid-subscription base (an unconfirmed figure). Spotify has 40 million active users, 25 percent of which pays.

While there’s still scope for Pocket to pull some genuinely awesome Premium features out of the bag in the future, I think it would have to be something truly special for this to be a viable plan in the long term. A better idea would have been to charge a one-off Premium upgrade, which I’m convinced many people would pay, irrespective of the perceived value of the new features. Granted, in Pocket’s case it might not open the floodgates to revenue, but people are happy to support services that they use. Subscriptions, however, could prove a step too far.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.