It’s the perennial problem faced by companies across the media spectrum, from music-streaming platforms to eons-old newspapers. How do you make money in an age where so many people have become accustomed to consuming content for free?

Advertising is the obvious conduit to monetizing digital content, but a more ideal situation is to have people willing to put their hands in their own pockets to pay for services. Yes, we’re talking about subscriptions, folks.

At the FT’s Digital Media 2014 event in London this week, this dilemma made it to the top of the agenda for a panel that included heads from Deezer and Dropbox, and author Nicholas Lovell.

Deezer has five million paying subscribers out of 12 million monthly users, and Mark Foster, MD for the company’s UK & Ireland business, noted that the reason for charging a subscription is two-fold – “to combat piracy and generate and retain value in the chain,” he says. The non-payers, of course, pay through lending their ears to adverts.

For Dropbox, with more than 200 million users globally and what’s thought to be around a 4% paid-subscription base (an unconfirmed figure), VP of Sales and Business development, Sujay Jaswa, says that they had a choice of building a business model that “took a lot of users and interfered with their user experience (e.g. advertising), or allowing them to pay for it via a subscription.” Dropbox, as you no doubt know, adopts a freemium model that serves up an ad-free basic version with limited storage, or more storage for a monthly fee.

But we’re not here to discuss the individual models of Dropbox and Deezer. More, what makes subscription work in today’s digital world, and are certain businesses better suited to adopting subscriptions over ads?

Non-friction subscription

“It depends on the scale on with which you want to operate,” says Jaswa. “Any time you add subscriptions, you create friction. So if you’re Facebook, there’s probably 100 million people who would pay something to use it. And yet their goal is to connect billions of people, so they know that a subscription model would create too much friction to build that network, hence they don’t move in that direction.”

So for subscriptions to work, you basically have to be comfortable with the notion that you won’t nab everyone on the Web as a paying customer. That much is obvious and makes sense. But for the people a company do want to lure on board as a subscriber, we’re seeing a myriad of techniques come to the fore designed to make the transition from freeloader a little soother.

“You really have to be confident that you’re delivering value to the customer,” says Jaswa. “Because if you expect someone to give you money, that level of friction is something that people have to overcome. And I don’t think you can build a subscription business without actually knowing that the value proposition is strong.”

Converting non-payers

Nicholas Lovell, author of The Curve, a book about how to make money when more people expect content for free, is very much against the subscription monetization model.

“I think both the ad-funded model and the subscription model are predicated on a pre-digital age, where it’s not possible to know your customers,” he says. “My background is in the games sector, and the games sector has absolutely figured out how to make money by giving stuff away for free.”

If the rise of mobile gaming has demonstrated anything, there is a bucketload of cash to be made by getting people addicted to free games, and then encourage them to pay for micro-transactions in-app. Just this week, King floated on the New York Stock Exchange, a move that was largely made possible due to the soaring success of its free-to-download Candy Crush Saga game.

Outside the gaming realm, however, one of the hardest things about getting people to pay is, well, getting them to pay. Encouraging someone to download an app, that is free to use and functional, is easy enough if they have an interest in the service. But getting them to subsequently commit cash to the proposition is another thing altogether.

Yes, when something is free, it’s hard to get people to pay. Within the newspaper industry, everything was free for a while online but now we’re seeing more publications erect paywalls – metered or otherwise – as they realize that their content is valuable. Reversing the reader mindset to agree with this assertion isn’t easy.

“It’s actually one of the hardest things in a freemium business – you’ve basically conditioned people to think that your product is free,” says Jaswa.

“I think the number one thing you have to do is create a value differentiation – people have to feel like they’re getting more in exchange for paying,” he continues. “If they feel like they’re really just paying for something that’s the free product, and they’re not really sure what they’re getting, or getting something that they don’t value, that’s where the problem kicks in. You really have to figure out where the value is for the customer, well beyond what their expectations have been determined by the free product.”

Lovell, on the other hand, believes subscriptions are doomed.

“In the long term, I don’t think people will pay for content, and I think the threat is competition, not piracy,” says Lovell. “It’s your competitors figuring out all the same high quality stuff you’re trying to sell and the things people will pay for…it’s how something makes them feel, in a social context.”

This is an interesting point by Lovell. He argues that people will happily pay for the idea behind something, rather than the product itself. And he uses an unlikely hip hop artist to illustrate this point.

“My favorite example is Mos Def who couldn’t sell his albums, ‘coz nobody would buy albums,” says Lovell. “But he sold a t-shirt for forty dollars which said ‘I paid for the Mos Def album’, then he gave you a copy of the album for free. What people were paying for, was the ‘I support this thing’.”

Today, this idea is very much alive across the myriad of crowdfunding projects that are realized because of the collective desire of the online masses.

“With Kickstarter, more often than not people are paying because they want a thing to exist, not because they want a thing,” adds Lovell. “And that distinction is very, very important.”

Early adopters, hipsters, or someone simply wishing to buy into a value system – this ethos could be one way for media companies to reel in the moneyed masses. But it certainly won’t work all the time. Plus, there’s that little issue of subscription fatigue to worry about.

Bundles and subscription fatigue

While some folks may be suffering from crowdfunding fatigue, others may be suffering from subscription fatigue. With phone bills, cable bills, home phone bills and all the rest, could we be reaching saturation point for the number of individual expenses that are debited from our bank accounts each month?

One of the responses from the communications industry, of course, has been to bundle what once may have been individual entities, into a single simple payment. So rather than having to remember $15, $12, and $27 leaves your account for Internet, telephone and TV each month, you just know that $54 is the figure that comes out. It’s exactly the same thing, but it just causes less anxiety.

But with subscriptions becoming more of a ‘thing’ across the media spectrum, including newspapers, magazines, movies and music, there’s going to be a heck of a lot of $10 and $20 debits to track each month.

“Sony gave a great talk a few years ago when they launched the PlayStation Plus Network, and said their research suggests that most of us have a working memory of between five and nine things,” says Lovell. “And we have that same thing for subscriptions – if we have to run through a list of subscriptions in our head, and a new one pops in that we hadn’t remembered, we go ‘Oh my god, I have too many….’.”

Indeed, Lovell says that for most people, the magic number is ‘seven’.

“The good news, is that the combination of bundling means we have fewer [to remember], and secondly we don’t count utilities (e.g. electricity), water, home phone, and increasingly we don’t count our television, mobile phone and Internet – because those are just must-haves, they’re not optional any more,” he continues. “This means that more slots have freed up. But we do count our gym, and we do count our music subscriptions, and we do count our Xbox Live subscription.”

Bundling is very much one way of getting over this sticker shock, and it’s something we’re starting to see more of. In November last year, Deezer started using Boku’s payment platform so users could elect to pay for their music directly through their mobile phone bills. Spotify too has previously announced a slew of partnerships with mobile networks and broadband providers, not only to help spread the good word via marketing, but also to ease the pain of yet another subscription.

Additionally, such partnerships can also exempt specific services (e.g. Spotify or Deezer) from any data caps associated with their mobile phone plan, which may encourage would-be subscribers to take the plunge.

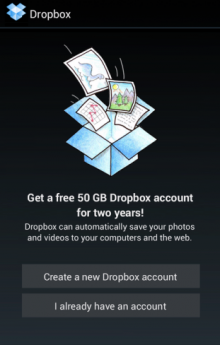

Dropbox too has been putting pen to paper with partnerships of its own, becoming a common sight on Samsung phones to help circumvent the competition problem. As the default storage option, users can back up their photos automatically to the cloud on a ‘free for two years’ plan, after which they realize the value of the service and don’t mind paying for the higher storage. In theory, at least.

Dropbox too has been putting pen to paper with partnerships of its own, becoming a common sight on Samsung phones to help circumvent the competition problem. As the default storage option, users can back up their photos automatically to the cloud on a ‘free for two years’ plan, after which they realize the value of the service and don’t mind paying for the higher storage. In theory, at least.

“It’s all about perspective, right?,” says Jaswa. “Paying a dollar for an app feels ludicrous, why am I paying for this app? But then if you’re buying a $30,000 car, paying another $2,000 for leather seats sounds totally reasonable. And so the thing that bundling does, is that it gives you perspective on what something costs. So for us, there may be friction in Dropbox costing $10 a month, but if you attach it to a $200-a-month bill, for example, it sounds like a deal. I’m a huge believer that bundling will work for subscription businesses.”

Deezer’s Mark Foster agrees.

“It gets us to scale, it gets the concept into the mass market, and also reinforces the concept of value,” he says. “It’s not ‘free’, but it is included and people by and large realize that content producers deserve to be paid for their work. So however you bring that to market, in a consumer friendly way, if you’re preserving that concept of value, I think it’s really important.”

Don’t diminish the free service

However a company decides to monetize, be it through advertising, subscriptions, micro-transactions or a combination, it’s important that they don’t try and force users into paying money by diminishing the free element of the service. Way back in 2011, we reported that Spotify was introducing restrictions to its free Spotify Open service that would come into force once a user was registered for six months. The changes essentially meant the free music playback was halved to ten hours each month, and some tracks could only be played a handful of times.

This move was only made in some countries, however, and late last year Spotify reversed this decision and made the ad-supported service completely unlimited again. “More access means more engagement,” explained Spotify’s Miles Lennon at the time. In other words, the longer someone has access to the full (ad-supported) service, the more likely they will be to pay to remove the ads and get offline access through the premium service.

Also, by reducing a free service, consumer confidence in a brand can be weakened, viewing the ‘free’ element of a freemium service as nothing more than a souped-up, short-term special promotion.

Image Credits

Image 1 – Shutterstock | Image 2 – Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.