Humans are great at telling stories. We use them to teach our children, to learn about ourselves, and to plan paths to the future. Speculative fiction, imagining worlds that are not our own, is a great tool for considering the societal consequences of things that haven’t happened yet, sometimes on a grand scale.

Designers also think about possibilities and potentials: What can be created to solve this particular challenge, or to meet this particular need? Often, the process of answering these questions involves building prototypes to test an idea. Once you get your hands on something and start using it, you reveal flaws and potentials that might not be apparent otherwise.

But in a world of fast-moving technological innovation, sometimes we don’t think enough about what the future looks like until it’s already partly here. Are we ready to decide who is responsible if a self-driving car kills a pedestrian? Or whether machine-learning algorithms can be discriminatory? If we start having these challenging discussions only when huge amounts of money and effort have been sunk into creating working prototypes, it may already be too late.

A group of design researchers is taking a new tack, combining storytelling and prototyping. They’ve created a new field of design known as speculative design, or design fiction. The term “design fiction” was coined by Bruce Sterling in his 2005 book Shaping Things. Sterling is well-known both as a designer and as an author of critically acclaimed science fiction.

However, beginning around 2009, it was work by Julian Bleecker that popularized the term — and started a research movement that’s becoming more and more prominent. Design fiction describes the practice of creating prototypes that are never meant to become real, objects “from another world.” These prototypes aren’t attempts to predict how things will be but to start a discussion based on what might be.

Design fictions are now widely used in research, by commercial organizations, and by artists who want to ask provocative questions. The Disobedient Wearables from Design Friction ask questions about data privacy and social marginalization. At Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum, a range of food-based fictions are on display until the end of September, including a cow bioengineered to provide more of the tastiest cuts of beef, and algae that integrate with the human body to let us survive on sunlight.

Some of these fictions can be pretty convincing. In 2015, a group of researchers from Lancaster University wrote an academic paper entitled “Game of Drones,” discussing a new set of regulations introduced by the European Commission that covered the use of unmanned aerial vehicles. The researchers described a system allowing members of the public to be “drone enforcers,” and provided a video demonstration of the concept.

The Drone Enforcement System turned civic law enforcement into a game, in which users could remotely pilot a drone to do things like looking for people parking where they’re not supposed to. The conclusion of the paper explained the fictional nature of the research, but some people were still fooled into thinking it was real — not only conference attendees who saw the work presented but also some of the editors tasked with reviewing the paper for publication.

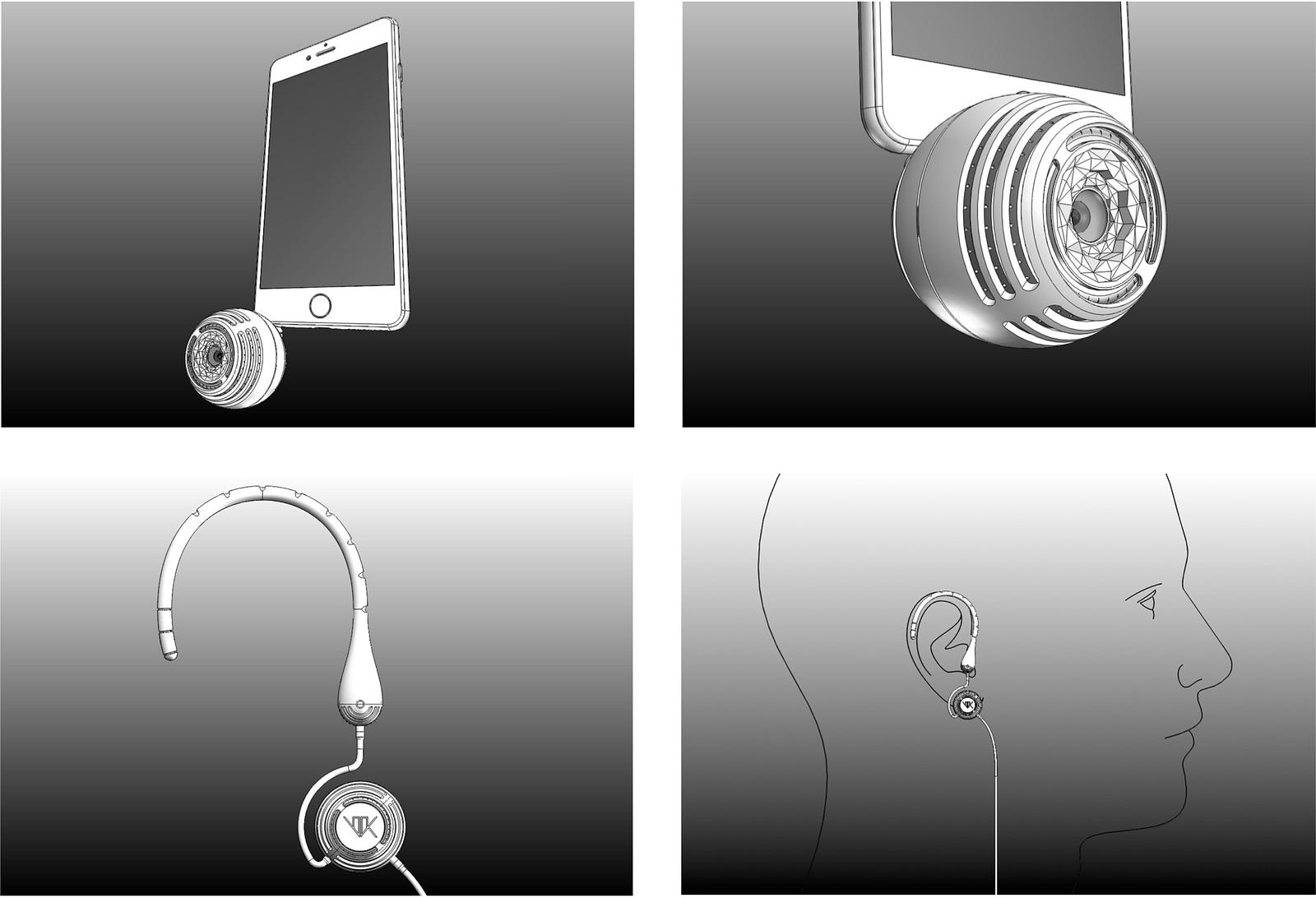

The same team also produced a “Voight-Kampff” machine, inspired by the “humanity test” of the same name from Blade Runner. In the film, a series of empathy-based questions provoked biological responses which could be used to tell if an individual was a human or an android. In the new design fiction version, the device attaches to your phone and measures reactions like heart rate and pupil dilation to tell you whether your date really finds you attractive. The team considered setting up a fake Kickstarter page, but decided that this would be too close to intentional deception. Despite this, they were contacted by a documentary filmmaker asking to cover the story and its progress.

The context can be important, too. In May 2018, The Verge uncovered a video shared internally at Google in 2016. The Selfish Ledger showcases how huge collections of our data might be used to guide people to fulfill particular life goals, either ones chosen by themselves or those reflecting “Google’s values as an organization.” Ultimately, the video suggests, it might be possible to sequence behavior as we do the human genome, providing a tool to predict or even manipulate people’s lives. When asked about the video, a Google spokesperson admitted that it was disturbing — but said that it was meant to be. The video was a design fiction created to provoke discussion within the company, and was never intended to represent real projects.

Most design fictions aren’t meant to deceive, just to provoke discussion. At the University of Aberdeen, where I serve as a research fellow, we’re using design fiction as a tool for academics to think about the implications of technology, and to bring some of these questions to the people it will most directly impact.

The TrustLens project is working with people in the Tillydrone area of Aberdeen. Tillydrone scores high on Scotland’s “Index of Multiple Deprivation,” and residents face many social and economic challenges. Increasingly, public bodies such as local councils are being sold on the idea that technology might improve urban spaces. The possibilities include connected sensor devices, which make up the so-called “Internet of Things.”

We designed a series of plausible uses for the IoT, such as smart litter bins that alert the council when they need emptying and call the fire department if smoke is detected. These concepts were turned into design-fiction objects: council information leaflets, bin ID cards for residents, and articles from local newspapers.

We then explored the consequences in a discussion with local residents. What information should the public get about these kinds of public space sensors, and when? How should data be managed to protect people’s privacy? Do we get any choice in whether our public spaces are tracked and monitored?

By creating touchable, relatable objects, we can not only tell stories but put ourselves in the story. Design fiction isn’t trying to give us a road map to the future, but it does let us make a decision: If a story like this were to become a reality, would it be a utopia or a nightmare? Would the genre be fantasy or horror? Once we know that, we have extra ammunition to make sure we get to the future we really want and need.

This story by Naomi Jacobs originally appeared on How We Get To Next, a non-profit project interested in exploring the intersections between science, technology and culture, and how those things are changing the future. Follow them on Twitter, Facebook, and subscribe to their newsletter.

TNW Conference 2019 is coming! Check out our glorious new location, inspiring line-up of speakers and activities, and how to be a part of this annual tech bonanza by clicking here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.