Quasars are found throughout the Universe, but quasar pairs are rare.

“We estimate that in the distant universe, for every 1,000 quasars, there is one double quasar. So finding these double quasars is like finding a needle in a haystack,” Dr. Yue Shen of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, explains.

These newly-recognized pairs are the oldest of the 100 or so quasar pairs currently known to astronomers.

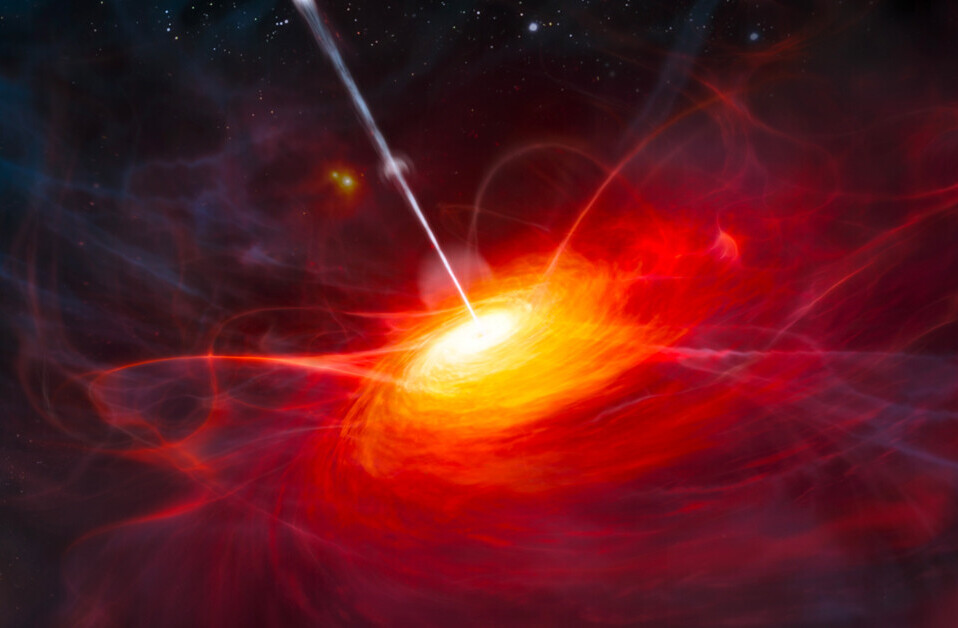

The quasar pairs examined in this study are seen as they were the distant past, less than four billion years after the Big Bang. As the quasars drifted toward each other, energy would have raced from the bodies, radiating into space. Eventually, the quasars would have merged into single black holes of enormous size.

Analysis of the study was published in Nature Astronomy.

Two quasar pairs seen in the early Universe are the oldest, most-distant bodies objects of their kind yet seen in the Cosmos.

Quasars are extremely energetic galaxies, powered by highly-active supermassive black holes near their centers. Matter falling into the behemoth void in the galactic core radiates vast amounts of energy out to space, forming a quasar. While this process is active, these supermassive black holes can outshine entire galaxies.

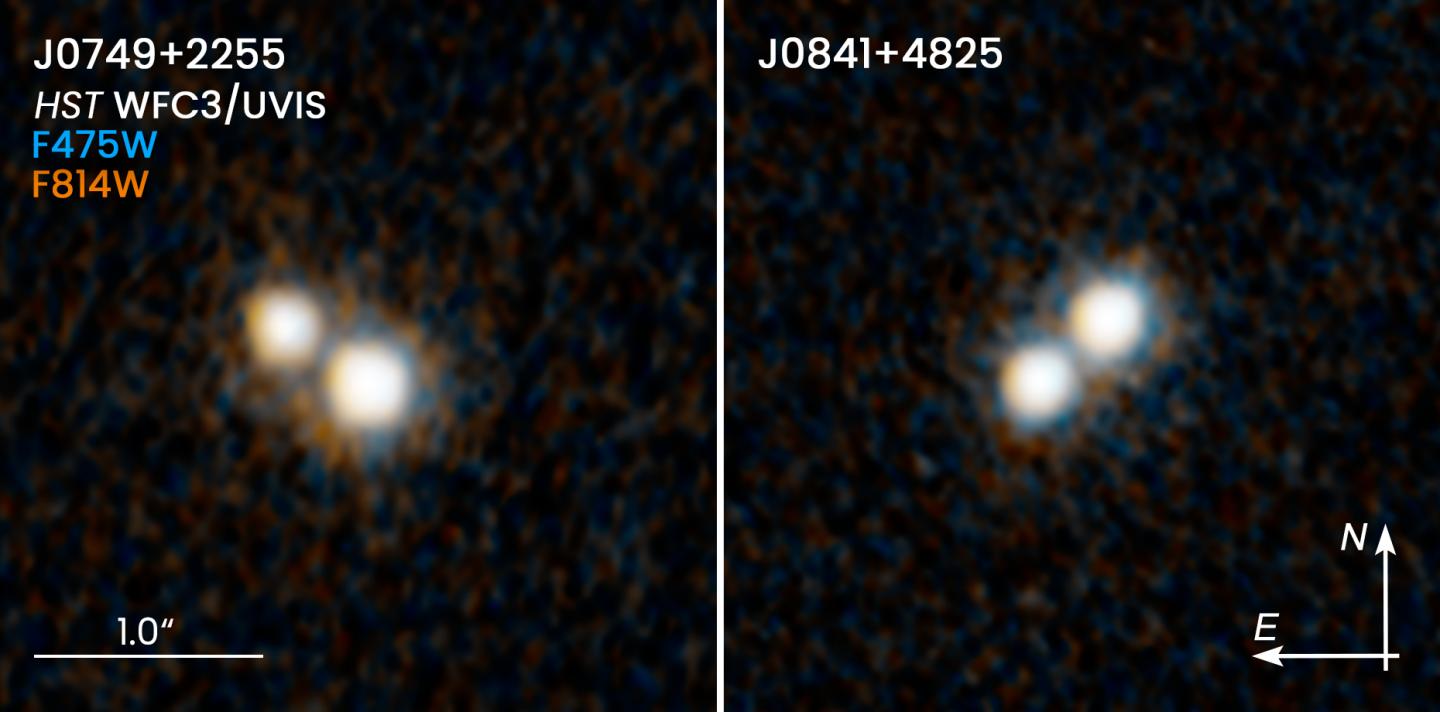

The quasars in each pair examined in this new study are just 10,000 light years from each other. This may sound like quite a distance, but this is just one-tenth the distance from one side of our galaxy to the other. This proximity suggests the quasars are found within merging galaxies.

“This truly is the first sample of dual quasars at the peak epoch of galaxy formation that we can use to probe ideas about how supermassive black holes come together to eventually form a binary,” explained Dr. Nadia Zakamska of Johns Hopkins University.

Paring down the pairs

Finding these quasars was the result of collecting data from several telescopes on and above the Earth, including observations from the Gemini Observatory.

One of the quasar pairs are seen as they existed 10 billion years before our time. Quasars are not exceptionally rare, but finding these objects in pairs remains a rarity.

Studying the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a 3D map of the Cosmos, astronomers selected 15 quasars for closer examination. These candidates were then matched with data from the Gaia spacecraft, narrowing the search to four potential quasar pairs. The Hubble Space Telescope was then able to resolve two of the pairs, showing separations between the pairs of enigmatic objects.

Using the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, researchers broke light from the quasars into component colors, allowing measurements of the movements of the bodies. This examination also provided proof of their positions, as well as information regarding their chemical compositions.

“Quasars make a profound impact on galaxy formation in the universe. Finding dual quasars at this early epoch is important because we can now test our long-standing ideas of how black holes and their host galaxies evolve together,” Zakamska said.

Although researchers believe these quasar pairs are in the positions they calculated, there remains a small chance that these pairs of images may be double images of lone quasars. This could occur due to gravitational lensing — the warping of light caused by a massive galaxy in-between an astronomical target and the Earth. However, researchers were unable to find any object in their view capable of causing this effect.

A long time ago, in galaxies far, far away…

Billions of years from now, our own Milky Way will, itself, become a highly-luminescent quasar. Every galaxy, including the Milky Way and our neighbor Andromeda, contains a supermassive black hole at their center. Currently, both of these are “sleeping giants,” only consuming small amounts of matter.

However, our neighboring galaxy and the Milky Way are approaching each other, and will one day collide. As the galaxies draw closer, the supermassive black holes at the cores of each galaxy will awaken. When this happens, highly-energetic radiation will bathe each galaxy, potentially killing off life on any worlds unfortunate enough to be too close to the galactic centers.

“Twinkle, twinkle, quasi-star, biggest puzzle from afar

How unlike the other ones, brighter than a billion suns

Twinkle, twinkle, quasi-star, how I wonder what you are” — George Gamow

Quasars are found throughout the Universe, but quasar pairs are rare.

“We estimate that in the distant universe, for every 1,000 quasars, there is one double quasar. So finding these double quasars is like finding a needle in a haystack,” Dr. Yue Shen of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, explains.

These newly-recognized pairs are the oldest of the 100 or so quasar pairs currently known to astronomers.

The quasar pairs examined in this study are seen as they were the distant past, less than four billion years after the Big Bang. As the quasars drifted toward each other, energy would have raced from the bodies, radiating into space. Eventually, the quasars would have merged into single black holes of enormous size.

Analysis of the study was published in Nature Astronomy.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.