Terms and Conditions May Apply, Cullen Hoback’s documentary on data privacy, is screening in LA this week and is rolling out to select theaters around the US over the next few weeks. It’s an illuminating film, and certainly a timely one, given the recent revelations from Edward Snowden about the National Security Agency’s surveillance program.

For those of us with active presences online, this is definitely a must-see. Here’s an exclusive clip from the film:

Once you’ve seen the film, if you’re interested in joining the call for better digital privacy, you can also check out trackoff.us, an activist project for the film created in partnership with Demand Progress.

Terms and Conditions May Apply is in limited theaters now and will be distributed digitally in the fall. You can visit the film’s site to find screenings in your area, or request a local screening through Tugg.

I sat down for a chat with Hoback to hear what he learned while working on the project and how can respond to these threats to our privacy.

TNW: When did you start making the film?

Cullen Hoback: About 2 1/2 years ago. I started by asking a very different question. I wanted to know how technology was changing us. The deeper I dug into that, the less I felt that it was technology itself that was actually what was changing us and it was something that was behind that technology. Every form of digital communication that we have now and most digital aspects of our lives have these long forms of service agreements attached with them, so we have a contract now with so much of what we do. Buried within that contract was the answer to my question, which is virtually the attempted death of privacy.

You’ve probably found that most people just click yes or agree. Were you the kind of person that did that when you first started? Have you changed?

Well, terms and conditions are designed not to be read. They’re designed to be invisible, and they’re designed to be unapproachable.

I’ve read my share of terms and conditions now. I don’t read them any more because I have a pretty good sense of what’s inside of them. In most cases they have access to control all data that goes across the website and the biggest problem that you find in most terms and conditions is they have the right to change it at any time. It almost doesn’t matter because they can change it in the future and in many cases they don’t even have to tell you.

Let’s do a bit of naming and shaming. What were some companies you found had the worst terms and conditions?

LinkedIn’s is abysmal. It’s the most over-reaching, ridiculous and shouldn’t be allowed to exist contract out there that I found.

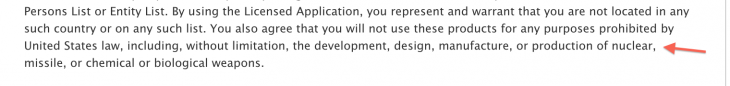

Apple’s is also ridiculous, but in a completely different way. They’re not interested in taking stuff from you, they’re more interested in protecting themselves. Apple’s goes to the point of saying that you’re not allowed to use their technology for nuclear warfare. That’s how far they go.

Most companies in Silicon Valley pay lip service to privacy. Anonymity isn’t profitable, and privacy isn’t necessarily profitable as far as they’re concerned.

Are there any good actors in the system? What are the companies you feel like are being up front and consumer friendly?

Twitter and Reddit are the two gold standards. At least in terms of how they’ve handled user privacy.

Reddit did a really good job in their current rewrite of their terms and conditions, making them much more approachable. Twitter’s terms of service aren’t necessarily that excellent, but they have stood up for users’ rights in a way that not a lot of other companies have. They also weren’t a part of [NSA surveillance program] PRISM.

Speaking of PRISM, when you were filming and researching this project how did the NSA stuff come up?

The film totally moves into the NSA, it’s a major part of the film. The thing about Edward Snowden is everybody’s saying it’s a revelation, but the reality is that there have been plenty of whistleblowers in the past. He just did a better job of it because he got the documents, and documents are hard to argue with, although they’re trying.

I see terms and conditions as a window into all of these problems. If you look inside of them, you can find government surveillance in there, you can find that they use these technologies to prevent things from happening, and you can find the more egregious data grabs in there as well.

I argue this in the film: ‘Web 2.0’ was really born out of 9/11. Suddenly for the first time, companies were required to retain data in a new and profoundly different way. As a byproduct of that, suddenly the companies could go, “Well, we have to hold on to all of this user data. If you have a problem with it, talk to the government.”

Not that it was directly responsible, but it certainly opened up the door for new products that had massive data retention like Gmail and Myspace.

Recently, Instagram took a lot of flack for trying to change its terms of service. What was your take on that whole fiasco?

What was fascinating was it was the first time that people really caught on because they could understand the weight of what was going on there.

Why would Instagram suddenly go out of its way to change the terms of service so that they can sell users’ photos? Well, they’re trying to turn their company to a point of profitability, but it goes to show you that your relationship with any of these online services that claim to be free is entirely based on trust. Your data is very sensitive, and your photos can be very private. The idea that you don’t own that really frightened people and alarmed them.

And I think Instagram went about it in a pretty dodgy way.

So what’s the solution? Do we just get off the cloud? Do we run from these services or is there a way to preserve our privacy and continue to take advantage of these technologies without running afoul of all these unfortunate side effects?

I think there are ways to use these types of technologies. I do think they need to be rethought and reconsidered with privacy at the forefront. The bigger solution is the idea of having access to our data and control over our data. So it’s the idea that data isn’t actually owned by the company, it’s owned by the user. So you could take that data somewhere else if you wanted to, you could delete it.

Data is ultimately a reflection of who we are. It’s us in ones and zeroes. That needs to be just as protected as the physical versions of us.

Do you live your life differently now?

Not profoundly differently because in order to be a modern member of society, you have to use these technologies. So I employ some data protection tools, I use Ghostery, Disconnect and Firefox in private mode. Sometimes I use Tor, but even if you use Tor, that just makes you more of a target for the government because they think you’re doing things you shouldn’t be because you’re encrypting your data.

What has the response to your film been?

People are scared and angry when they’re done watching the film. They want to do something. That want to learn how to protect themselves and they want to know how to fix it. That’s why we’ve been working with [civil liberty advocate] Demand Progress, and we’ve developed a website called trackoff.us. We’re starting by petitioning congressmen to see the film, but it’s going to evolve into a platform for broader activism surrounding these issues.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered in the process of making the film?

For me, I still think the idea that these terms of service agreements show that the government is using these technologies to prevent crime from happening, that is the scariest aspect. But, the broader, more frightening problem is the idea of retrospective surveillance and that if all of this information, all of this web traffic, all of our conversations are being stored, you can go back and turn anyone into a criminal.

One recent theme is that for a company that sells advertising, such as Google and Facebook, the users stop being their customers. What kind of impact does that have on the way these services are developed and the way they treat privacy and user data?

If you’re a company and your client is another company, you’re going to base your decisions on how to make the most money and how to serve that company. If your product is these people, you need to keep the people happy enough, content enough, but you’re not going to necessarily put the rights of these people first unless the CEOs behind these companies have a clear ethical philosophy in how they approach it. I think Twitter is the example right now. I think Apple used to be.

That’s why it’s so hard to trust any company with your data when it’s permanent, when they own it. You never know what’s going to happen to that company in the future. they may go public and their motives change, they may sell the company like what happened with Instagram.

If you understand the nature of the trade, you may rethink the trade. I don’t think a lot of people when they started using Gmail, or any of these services, really understood what they were giving up, what the potential cost is of this trade. Your data is worth what, $500 a year to Google? That’s a lot of money. If you had to make the choice of “Am I going to pay Google $500 or am I going to pay with my data?”, at least you’d understand how much your data is worth.

I don’t think it’s fair to call these services free.

Do you think services like Snapchat are a counter to the scary permanence of data that someone like Google or Facebook has made?

I think that Snapchat and services like it definitely represent a desire. That desire is being able to do things that we don’t have to have attached to us in perpetuity, forever. Being able to act ridiculous, send someone a picture that is racy, do these things without there being ramifications.

So, I definitely think that’s a part of it, but can the NSA see those things along the way? Sure. It’s not necessarily full privacy, but it definitely speaks to the desire. We need things that can expire.

It’s fascinating showing the film because I have all these people coming up to me with all these new stories. There was someone who was saying he specifically writes the code that handles user data and the privacy around that and he said they had to completely rewrite the code for Germany. It hadn’t even crossed my mind that you could write it regionally, restructure the code and actually build user privacy in. They’re doing it, they’re following their specifications, which means that laws that protect our privacy can work and they can be employed on a state by state if not on a national level.

But what it means is it’s possible to build privacy into these systems. I doubt he was working for Google. He was probably working for some smaller company that couldn’t afford the fines.

We’ve been seeing an increasing number of films [such as Henry Alex Rubin’s Disconnect] that have been dealing with this subject, asking questions like: What is technology doing to us, how does it affect society, does it make us more alienated?

Yeah, those were the questions that I started with. It’s almost this idea that if we just keep using more technology, we’ll dig ourselves out of the technology hole. Somehow if we just have enough technology, it’ll finally connect us in the way that we’ve always wanted to be connected. What’s crazy is that the more we do this, the more it’s just the technology talking to itself and not us communicating with each other. It’s certainly making us less human and more cyborg.

How do you feel about Google Glass? That seems like the next level of privacy, or lack thereof.

I don’t think they did any research on me, but I got a pair from them, just to test them and see. They do scare me and I wanted to see if my fears are validated and they are. If you have it in real-time it’s uploading to their cloud and the potential to access that camera, what that camera can do with apps in the future, is very frightening.

I know they’ve said that it’s not going to be integrated with facial recognition software, but of course that’s going to happen.

My favorite example is say you have an app that helps you with pickup lines. And all the data that it knows about the person who’s over there, well maybe it’ll feed you a pickup line that it thinks has a 98 percent chance of working. It’s not even you thinking anymore of that relationship with another person, that’s what I mean about the technology talking with itself.

That reminds me of Sight, this futuristic short film about augmented reality contact lenses where a guy uses a wingman app to pick up a woman on a date and then hacks her lenses.

That’s definitely where the technology is headed. Right now you have these big clunky things and we’re all, “It’s kind of inconvenient to put these things on my face every day. And man, I have to talk to it? What if I could just think to it? That would be so much more efficient and convenient.”

Then suddenly it’s in your eye, then suddenly it’s in your body.

As a huge fan of science fiction, I understand the excitement there, but there are also fears too.

That’s the hard part too, is you’re like these things are cool, you want to try them. There’s a shiny new button factor to them. That’s what motivates us sometimes to keep moving forward with these things.

I don’t know if augmented reality is making us any happier. Nor do I think Google Glass is going to make us any happier. There have been plenty of studies and statistics that show that Facebook just makes people unhappier.

One thing I will say, the cellphone enables us to be anywhere. Specifically, being able to have access to email and the Internet from anywhere, that’s a really valuable proposition. It allows me to live the kind of life that I do. In that sense, it has certainly made my life better. I don’t have to sit in an office all the time.

In the film, I detail some of these surveillance vendors, the companies that are out there that heavily solicit the government on purchasing their latest cellphone data extraction kit, an easy way to gain rogue access to your target’s Facebook or Gmail accounts. This guy from Cellebrite says to me, “It’s no different than manufacturing a Glock or a Beretta. We’re just making the device.”

There’s this notion that the companies have no responsibility in what they’re developing, but someone has to have responsibility, right?

Everything is brand new and it’s happening at such an insanely fast pace, how do you keep up with it? Ultimately, I think we just have to step back and say, “Should the Constitution apply online?” If the answer is “Yes”, that solves a lot of problems because it forces companies to have to rethink the way they design these technologies. We just have to require it, otherwise it’s just going to be status quo and they’ll just keep making money off of our data and privacy will not exist.

If you want to hear more of Hoback’s thoughts on terms of service and online privacy, you can request a screening, catch it in theaters or wait for the online release in September.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.