This is the fifth in our Future Of series, where we analyze and dissect one facet of life that’s been impacted by digital technology. Today, we look at radio.

“[Radio] is the original form of ‘social media’ in that it allows you to connect with other people and ideas in your community or beyond, for free; this is what makes radio unique and the reason behind its longevity. Terrestrial radio is growing as well as the Internet and online radio – the entire pie is getting bigger.”

– TuneIn CEO John Donham

A recent report by Nielsen found that traditional broadcast radio is still the preeminent means of consuming radio in the US. According to its research, almost two-thirds (63%) of music fans say that (traditional) radio is their chief means of discovering new music. Of course, that’s not to say alternative means of consuming radio aren’t rising in demand too – it just means that your trusty ol’ FM/MW wireless remains a force to be reckoned with. For now, at least.

“The accessibility of music has seen tremendous expansion and diversification,” explains David Bakula, SVP Client Development, Nielsen. “While younger listeners opt for technologically advanced methods, traditional methods of discovery like radio and word-of-mouth continue to be strong drivers. With so many ways to purchase, consume and discover great new music, it’s no wonder that the consumer continues to access and enjoy music in greater numbers.”

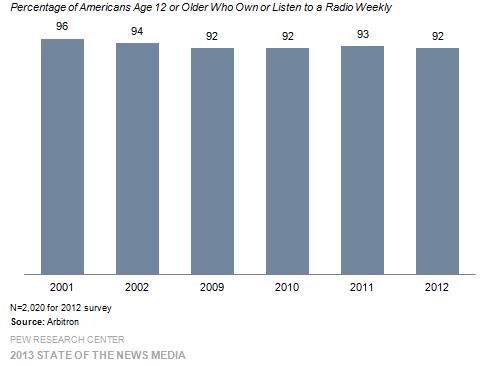

More broadly speaking, the percentage of people in the US who listen to AM/FM radio each week remained pretty much the same in the ten year period leading to 2012. According to data from the Pew Research Center, 92% of Americans aged twelve and older listened to broadcast radio at least once a week, a mere 2% down from 2002.

Indeed, only a third (33.4%) of all radio sets sold in the twelve months ending June 2013 included a DAB tuner, though this was up from 28.7% in the previous year. And over the same 12-month period, around a third (33.9%) of all radio listening hours was through digital radio, which includes DAB, digital TV, the Web and mobile apps. This represented an 11.2% increase on the same period in 2010, and a 4.4% increase on 2012.

So DAB radio is increasing its market share in the UK, but it’s still outnumbered by FM – a broadcasting technology that came to the fore in the 1930s – by a mark of 3-to-1. But why hasn’t DAB caught on as quickly as it could’ve done? Roy Martin, founder and editor at UK publication Radio Today, tells us it just comes down to the proposition on the table:

“Traditional FM radio offers reliable sound and has decades of historic listening behind it. Unlike television going digital, which offered dozens more channels, HDTV and interactive services. Radio on digital isn’t offering enough extras to make people switch.

It’s also worth looking at cars – a bastion of radio-listening for decades. According to Ofcom, almost two-thirds (61.7%) of new automobiles still aren’t fitted with DAB radios as standard.

While the UK’s televisual switchover from analog to digital is all but complete, radio’s future is still uncertain. The country’s Digital Radio Action Plan stipulates that any forced switch to digital broadcasting will only happen when the market’s ready for it – when more than half of all radio listening takes place via digital, when DAB coverage is on a par with FM nationally, and local DAB coverage hits 90% of the UK’s population.

So radio can perhaps be filed somewhere alongside vinyl records and movie theaters. It’s been threatened by new and emerging technologies since, well, forever, but it seems somewhat resilient to change. But things are changing…just that little bit more slowly than some may have anticipated.

From the dots-and-dashes of wireless telegraphy in the late 19th century, through the first public broadcasts of the early 20th century and on to the algorithm-driven, personalized music stations we see strewn across the Web today, ‘radio’ as a concept has evolved for sure. But what does the future hold for the age-old medium?

We took a look at the current state of play to see what’s out there, and touched base with some of those working at the xxxx. But first, what is radio?

Defining radio in the digital age

Radio isn’t what it once was. That 30-year-old battery-powered work-of-art that sits on your bathroom window sill may be what you immediately think of in terms of ‘radio’, but it’s now so much more than that. The lines where radio and music-listening meet have blurred, making it difficult to distinguish what’s what.

In the analog days or yore, it was easier to differentiate ‘radio’, from someone listening to music, say, on their record player. Now, with Spotify, Pandora, podcasting and all the rest, the waters have muddied.

At a Music 4.5 event in London recently, a number of key movers and shakers from across the industry gathered to discuss whether we were moving towards the death of music radio. Mark Mulligan, and analyst from Midia Consulting, attempted to define what radio actually means in 2013. “If all radio is, is an antenna broadcasting content, then how is that different – other than the delivery technology – to something that’s streamed to your computer?,” he asked. He gave a handful of broad categories encapsulating what could be construed as radio today:

Traditional and DAB

For all intents and purposes, we can actually just lump digital radio (e.g. DAB) and traditional (terrestrial) radio together into one category. Sure, the quality may be better on digital, but they’re both essentially the same medium – dedicated devices for listening to broadcast radio.

Interactive Radio

Then there’s interactive radio on your PC, smartphone or tablet, which lets you open a specific app and gives you more control over the radio station in question, but it’s essentially still ‘radio’, insofar as it adheres to a linear broadcast schedule. There is often the added bonus of being able to access catch-up content too.

Podcasting

Popularized by the advent of the iPod era, podcasts typically offer episodic shows, similar to how radio shows have been broadcast for decades. However, when you downloaded them all in one fell swoop to a portable media player, you can listen to them in any order and they become part of your broader music and audiobook collection. The lines are blurring indeed.

Subscription services

Much like radio, Spotify, Deezer, Rdio et al are all about access over ownership. But here, you must pay anything up to $9.99 a month to access the full array of features, such as mobile and offline access.

You have an unlimited amount of music at your disposal, which you can hand-pick from and create playlists, or tap radio-like features that play music randomly. They may even learn what you like over time and improve accordingly.

Web and mobile streaming services

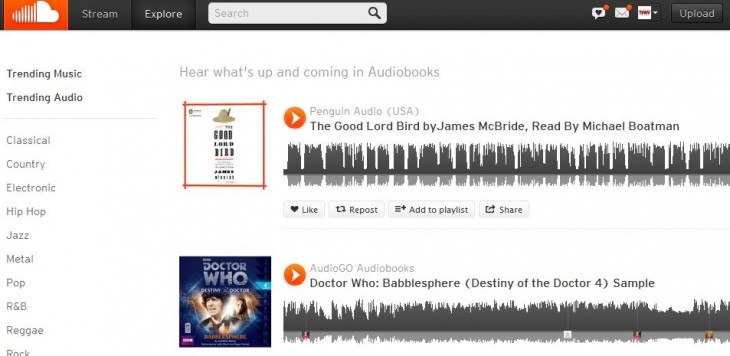

The likes of SoundCloud behave a little like a subscription service, but it includes other kinds of audio too…including podcasts. Also, it may run contrary to your intuition, but sites such as YouTube, Vimeo, Vevo and all the rest encroach on radio territory too. YouTube may be a video site, but it can also be used as a radio-like platform, letting you subscribe to other users and queue up audio to listen to in bed.

Does it really matter what’s called ‘radio’ though? Mulligan reckons not – he says it doesn’t matter if its digital or anaglogue, on-demand or scheduled. “It’s really just about whether they’re competing for the same consumer hours (as traditional radio), and whether they’ve contributed to its growth.”

Notable players

There are a myriad of mobile apps designed to help you find new music, but who are the real big dogs from the radio space? Here’s a quick snapshot of some of the key players, the ones who have been shaking things up, and who could give us some idea as to what the future holds for radio.

Spotify

This could perhaps be Deezer or Rdio or others. But Spotify is the cool kid in town and, with more than $500m funding under its belt ($250m just recently), it will only go from strength to strength.

Sure, Spotify is perhaps more synonymous with music-streaming than radio per se, but as we’ve noted already the lines between the two are blurring. Spotify Radio, for example, lets you pick a genre of music and it will play tunes accordingly. You tell it what you like and, over time, it learns and improves.

Last.fm

Launched initially way back in 2002, Last.fm is actually something of a veteran of the online radio space. Similar to Spotify Radio, Last.fm builds a profile of users’ tastes by tracking details of the songs they listen to – both from Internet radio stations and a user’s own music collection.

Last.fm is a stalwart of online radio, though it’s not clear what the future may hold for it with so many other plays in the space. Pandora offers something similar, but is only available in the US, Australia and New Zealand, while iHeartRadio does something similar for the US market only, offering customized stations from actual broadcast networks.

Sirius XM Radio

Sirius XM Radio is one of the most well-known satellite radio services, serving up dozens of channels of music, sports, talk, comedy, news, traffic, and more. It’s available in North America only.

Given the subscription services uses satellite to broadcast, it covers a much broader area and is particularly useful for those who drive a lot in remote areas – no 3G, MW or FM signals required. To help it compete with Spotify, Pandora and the likes, it also offers an Internet radio service with mobile apps too. But Sirius is all about the satellites, really.

SoundCloud

SoundCloud is an online audio platform that lets anyone record, upload and share their own music and podcasts. Indeed, it’s used differently by different people – on the one hand, it’s great for networking and discovering new DJs, but it’s equally good for unearthing some great talk-based programming, including audiobooks. It has gone some way towards democratizing the broadcasting industry…anyone can be a DJ with SoundCloud.

Audioboo

Launched in March 2009, Audioboo allows users to record a near-unlimited quota of audio snippets, which they can share with friends or broadcast to the world. They can also add images, titles and tags and upload it to Audioboo.fm, complete with biographical and geographical information on where and when it was recorded. It turns out Stephen Fry is a huge fan of the service too.

TuneIn

TuneIn is a massively popular cross-platform service that lets you search and listen to thousands of radio stations, covering every genre of music, on-demand shows, podcasts, concerts and interviews. It’s essentially a radio search engine and audio-player rolled into one. Stitcher Radio is similar, except it focuses more on talk-based programming.

The Echo Nest

The Echo Nest isn’t an online radio service as such. In fact, you possibly have never heard of it. But its data arms many of the major online players to build smarter music apps. It also recently launched its new Music Audience Understanding service, which lets streaming services and ad networks draw on rich data about the kinds of people who listen to specific tracks. Why? For smarter adverts, of course.

Apple

It would be a folly to ignore Apple’s efforts in this space. Sure, iTunes itself pretty much kickstarted the podcasting revolution, but the recently-launched iTunes Radio could prove to be a major contender once it shakes off its US-only credentials (hopefully not much longer to wait).

It offers a number of featured stations centered around genres, eras and celebrity-curated playlists. But you can also create your own stations from single songs, artists or genres. Yes, it may be a little like Pandora or Last.fm, but iTunes Radio has the might of Apple behind it.

BBC

The BBC’s wealth of innovations may largely be focused on UK shores, but it’s an organization worth observing for its R&D in the digital sphere. It’s dabbling in perceptive media for TV, and then there’s the BBC Audio Research Parnership, which has brought together a slew of top audio experts for a five-year research collaboration.

Last year, it also spun out a new standalone iPlayer radio app, while just a couple of months back the broadcaster launched Playlister, a service that lets users save the tracks they’re currently listening to online or in-app, and transfer them as a playlist to third-party services such as Spotify, Deezer and YouTube.

But why, exactly, does radio prevail?

Why radio prevails

While it’s clear that radio is evolving to some degree in line with digital innovations, it’s equally clear that changes perhaps aren’t as pronounced as you may expect. Why is that?

Well, there is this general assumption that digital always equates to the death of its analog predecessor. And while that has proven to be the case in some spheres (e.g. photography), there’s often good reason why things don’t transform quite so readily elsewhere.

“Radio is the oldest mass medium, and it has worked well for nearly a century,” says John Donham, CEO of uber-popular radio station aggregator TuneIn. “It’s the original form of ‘social media’ in that it allows you to connect with other people and ideas in your community or beyond, for free; this is what makes radio unique and the reason behind its longevity. Terrestrial radio is growing as well as the Internet and online radio – the entire pie is getting bigger.”

So digital and analog radio could continue to grow in harmony, and there may be a number of reasons for this being the case. Indeed, until we’re at a stage where 3G and WiFi is 100% reliable and ubiquitous, those crackly interference-infused score updates you listen to through your headphones at football matches could continue for a while yet.

“Radio has been around a long time, it’s deeply embedded in our lives from homes and cars to the workplace, it’s cheap and it is easily accessible by all ages,” adds Simon Moran, Managing Director of Last.fm. “There’s no Internet access issues and you can buy a cheap radio for a few pounds. I can see it going strong for a while yet, but there is a real shift towards Internet radio and streaming – DAB uptake has been slow, but Internet streaming has evolved rapidly which will continue.”

Rob Proctor, CEO of social audio platform Audioboo, agrees that digital platforms aren’t necessarily out to replace terrestrial, and reckons the new tools can be used in conjunction with old tools to bring something much better to the table.

“Many digital audio platforms are not there to replace traditional broadcasting, but to allow these broadcasters to take their content further – and to new audiences,” he says. “Online platforms like Audioboo open up the social media world, meaning that quality content has a longer shelf life.”

The sound of music

I recently heard a speaker at a music-industry event say that the success of terrestrial radio suggests that most people don’t care about high-quality audio when listening to music. So could this partly explain why FM and AM radio continue to thrive?

”I think people do care about high quality sound, which is why we’ve had the number of sales for (digital) DAB so far,” says Radio Today’s Roy Martin. “They’ve been lured in by the promise of ‘CD quality’ sound, only to realize once they find the station they want to listen to, it is in mono and 80Kbps.”

Okay, so perhaps the broadcast quality isn’t of a consistent enough quality across the board yet for digital radio sets to be useful 100% of the time. And, of course, there’s no right or wrong answer to the question about people’s quality preferences – many people are happy listening to a melodic, acoustic tracks through a cheap, single-speakered radio.

“There are audiophiles, but I would agree that the majority of people are not particularly picky about sound quality,” offers TuneIn’s John Donham. “If you look at the progression of music formats over recent years – moving from records to CDs to MP3s – it seems that the sound quality worsens with each audio innovation, yet people are consuming audio content more than ever before.”

Last.fm’s Simon Moran agrees to a degree, but compares radio to the TV realm to illustrate many people’s indifference to high-quality broadcasts – but only initially.

“I would say the difference in quality obviously isn’t enough for people to run out and buy new radio equipment straight away,” he says. “HD & TV is a classic example – generally people weren’t particularly bothered about upgrading until they needed a new TV. Once they saw the difference in quality, well, they understood. The promise of better quality isn’t always enough to guarantee people switching straight away, but it does happen.”

Ultimately, it likely just comes down to the specific activity people engage in around radio, and the location they are in. In the bathroom, for example, an old rickety, battery-powered contraption with tinny sound may suffice. In the lounge, with access to power sockets, cables, speakers and more, something stereo and with a little more bass might be preferable.

Keep the cars running

It would be foolish to ignore the role cars play in the continued success of radio – both terrestrial and digital. It’s thought that roughly half of all radio-listening in the US takes place inside an automobile, so the market here is potentially huge.

While traditional broadcast radio continues to thrive in-car, there has been a huge push from companies such as Pandora too – it has been activated in more than 2.5 million vehicles, through integrations with over 20 car manufacturers and eight third-party stereo brands. Pandora says it expects to ship in a third of all new vehicle sold in the US this year alone.

Moreover, Spotify also announced a partnership this year that would see it integrate with Ford’s SYNC AppLink. The upshot? Voice-activated music control in more than one million cars. This was followed by a tie-up with Volvo too, which will see it launch a voice-activated music streaming service integrated into the car manufacturer’s touch-enabled dashboard. Basically, drivers will be able to stream music from Spotify’s servers using a 3G/4G dongle, or a mobile phone connection tethered to the dashboard.

Even Napster’s at it – it recently announced a partnership with BMW ConnectedDrive which will see the music-streaming service made available in all BMW models from 2011 onwards. Users connect to BMW ConnectedDrive via their iPhone, which hooks up with the iDrive controller – essentially a central computer system that communicates with the entertainment controls in the car. Rhapsody – which acquired Napster back in 2012 for its European expansion – announced a similar integration for its US business.

TuneIn too has been racking up the partnerships – the list could go on.

“Half of all radio listening happens in the car, so we see that as a very important front,” says TuneIn’s John Donham. “That’s why we’ve dedicated a significant portion of our resources to getting TuneIn into the dashboards of cars around the world. We’re in more than thirty models from manufacturers such as BMW, MINI, Ford, Tesla and GM, and this list is only getting longer. People want a lean-back experience while they drive, and radio is the perfect service for that.”

As noted already, Sirius XM’s trump card over rival radio-based companies is that it doesn’t require an Internet connection, and it doesn’t need to worry about FM/AM restrictions or reception issues. Its satellite radios are installed in 70% of new vehicles, with most of its revenue garnered through subscriptions – 24 million people currently pay for the service, culminating in $3 billion in revenue each year.

The omnipresence of satellite radio should see Sirius succeed in cars for some time to come, but with WiFi likely becoming more of a feature in the cars of the future, Internet-based radio services from the likes of Pandora and Spotify will likely gain traction in many more verticals.

However it all pans out, cars will be a ripe battle ground for radio in the short- and longer-term future.

Entertained by algorithms

Many modern online radio services promise ‘smart’, ‘automated’ and other buzzword-filled adjectives. So does this mean people no longer want to place their trust in a human DJ to surface content and ‘entertain’? Do people really want to be entertained by algorithms?

“The dominance of social media means that consumers are increasingly used to discovering and curating their own content,” explains Audioboo’s Rob Proctor. “Word of mouth recommendation is also hugely important – people often look at what their friends are listening to and use this as a starting point. That all said, there will always be trendsetters and influencers whose opinions are highly respected, and who can be responsible for bringing new content to the forefront. The difference is that those influencers now have a huge choice of platforms through which to speak to their audiences, whereas ten years ago traditional radio was their only mouthpiece.”

A hybrid world of automation and curation is great, but it could get harder to find those people we trust to surface new music on our behalf. This is a problem across the media realm – through the cacophonous crackle of the white noise Web it can be difficult to zone in on the stuff and people we really like.

“People want and need real radio, there are really only two ways to listen to anything: your personal music collection and radio,” continues TuneIn’s Donham. “People will always use both for various times and needs. We’re finding that people grow tired of repetitive playlists, which isn’t an issue with real radio. Plus, real radio offers sport, news and talk shows: something you’ll never hear on an on-demand music service.”

There is a lot to be said for removing ‘thinking’ from the listening process. By that I mean people lead busy lives, and if they can simply flip a switch on their dusty FM radio at the same times every day, and be greeted by familiar voices discussing the top stories of the day, sprinkled with a tonne of new music, well, what’s not to like about that?

“We’ve also seen Apple hiring content experts to incorporate human curation into its own iTunes Radio algorithm, as well as services like Songza that rely completely on human curation to serve up playlists,” adds Donham. “There’s no question that listeners value this curation and expertise, and these new services are trying to emulate what TuneIn inherently offers, which is human-curated content that is dynamic and hassle-free.”

So…what does the future look like?

Often when gazing into a crystal ball, it can be tempting to think of all the extreme potential future scenarios – you know, fridges with speakers on them. That kind of thing. But things rarely end up being all that whacky in reality.

With radio, we’ve seen a big shift towards automation, personalization and democratization, but that doesn’t mean that ten years from now radio will be devoid of professional DJs tasked with unearthing new music, giving it context and meaning to the listeners.

With news, I like to place a little trust in the ability of professional journalists and organizations to unearth and report on the news it believes I should know about. That’s why I watch the half-hour evening bulletins to get a quick snapshot of the basics. But if I want to know about more stuff, I’ll go perusing through my Twitter stream, boot up the BBC News app, read Time magazine, or one of the many personalized news services out there.

With radio, it’s much the same. People like people – conversational tidbits, cheery voices, new music they don’t have time to search for themselves. The future of radio will very much include that, but with the added bonus of all the other cool innovations the likes of Spotify, TuneIn, Last.fm, Pandora, Audioboo and all the rest.

“FM and AM radio will still be operational ten years from now,” says Radio Today’s Roy Martin. “Five-year licenses for new AM and FM radio stations, which are three or four years away from launching, are still being offered.

“However, a few of us have been saying for years that the future of radio is multi-platform,” he continues. “A single radio which tunes in to any station regardless of transmission method. How ugly is it seeing a radio with ‘FM’, ‘AM’, ‘LW’, ‘Internet’ and ‘DAB’ on, not to mention frequencies and multiplex numbers, then having to find a station by frequency on a small display. I want to listen to Kiss, but have to work out what platform it’s on, then find the frequency or Internet URL.”

What Martin is positing is that the big guns from Roberts, Pure, Sony and so on start introducing a truly modernized radio with a big touchscreen and compendium of stations listed alphabetically, alongside their logos. Kind of like a jukebox…but for every radio station…something that automatically knows if a particular station is on FM within their local area, or whether it requires a Web connection.

It transpires that a prototype of such a device does exist, courtesy of UK Internet radio service Radioplayer, a platform backed by the BBC and a number of other commercial partners. The hybrid ‘kitchen radio’ lets listeners browse radio stations regardless of how they’re transmitted, and Radioplayer has been in discussions with manufacturers on how the idea could be progressed.

It’s perhaps worth dwelling on the screen element of such a device too. We are beginning to see more visual elements creep into the radio experience, as with SoundCloud. Its giant waveform spans an artist’s page, with user comments popping up as the song scrolls along.

TuneIn’s Donham agrees that there will always be a need for radio, and reckons that the overall market will grow – both digital and terrestrial. “Our research shows that digital is only serving to grow the overall listening, not cannibalize it,” he says. “It’s a free mass medium that everyone wants and needs – which is particularly evident around disaster situations whether it’s a hurricane, tornado, flood or fire. Radio is often the only communication that dependably continues.

“However, in order to continue to evolve and grow the attention of the modern listener, new radio consumption models must be introduced to align with their habits and expectations to have all content available anywhere at all times,” he continues.

Terrestrial broadcast radio, as we know it, has a lot of life left in it yet. But it will surely be usurped by digital at some point in the future?

“I think there will always be a place for traditional terrestrial radio, but with technological changes, listening habits such as mobiles and tablets, programming changes – on-demand, curation – will eventually mean that the growth will be in online, with listening through terrestrial radio decreasing slowly,” says Last.fm’s Simon Moran.

Audioboo’s Rob Proctor also reckons there will always be a place for traditional radio broadcasting – “…it’s too engrained in people’s lives and habits to completely die out,” he says.

“But I think that digital platforms that allow the consumer to create their own content are ultimately shaping the industry,” he continues. “Now, you can create your own playlist – a mixture of interviews, news, music – whatever you want, and listen to it at your leisure. I think that’s key. The younger generation aren’t used to tuning in at a specific time to catch a specific program. They want to be able to curate their own highlights, listen when they want and be able to interact and share with their peers at the touch of a button.”

So perhaps it will require one or two more generational shifts for radio to completely evolve. Radio won’t just survive though, it will go from strength to strength and could become bigger than ever. However, you may have to completely rethink what ‘radio’ actually means.

Image Credits

Feature Image – Shutterstock | Image 2 Shutterstock | Image 3 Shutterstock | Image 3 Shutterstock | Image 4 Shutterstock | Image 5 Shuterstock |

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.