What does it mean to be nostalgic for outer space? Outer space supposedly summons images of the future and the beyond, hence its blatantly colonial fantasy nickname — the final frontier. Yet proposed travel to outer space these days is a backward-looking endeavor. The angel of history has become an astronaut.

In 2018, Donald Trump’s proposals for a U.S. Space Force are a redux of Reagan era “Star Wars” and its vision of omnipresent military might. Space entrepreneurs evoke a mythical heyday of unbridled growth from the wild, unregulated west.

I too am nostalgic for outer space, but for one that never existed in my time, before white men with lots of money or state power (or both) were the only way off the planet. And I am nostalgic for the wild-eyed optimism-of-the-will-and-spirit practiced by spooky heartthrob and sad(ly) federal agent Fox Mulder, who said — and I repeat — “I want to believe.”

I want to believe that there is a way to think about space differently. The conflation of space and outer space is intentional here: outer space is the place for us to think about the relationships and organizations of our lives here, on Earth, such that they might be resilient out there.

The speculative might be a persistent genre of popular interest in part because we intuit that the shape of our world, and now the shape of outer space, are formed from the speculations of financial capital. But against the machinations of banks and corporations, there have been other ways to imagine the future. The pictures we have been given of outer space and of who gets to go there are not the ones we have to accept.

On September 17, 2018, Elon Musk tweeted a picture of himself in black pants, a black T-shirt, and black boots, posing in front of the American flag-adorned Falcon Rocket 9. He must think that he looks really cool (a belief so many people indulge him in). In the photo, perched on Musk’s shoulders is Yusaku Maezawa, a man who made millions as the CEO of the online retailer Zozotown and garnered international attention for spending the most money ever — $110.5 million — for an American artist’s work at auction, an untitled Basquiat painting from 1982. In Musk’s tweet, Maezawa is also dressed in billionaire basic style (normcore taken up a few tax brackets).

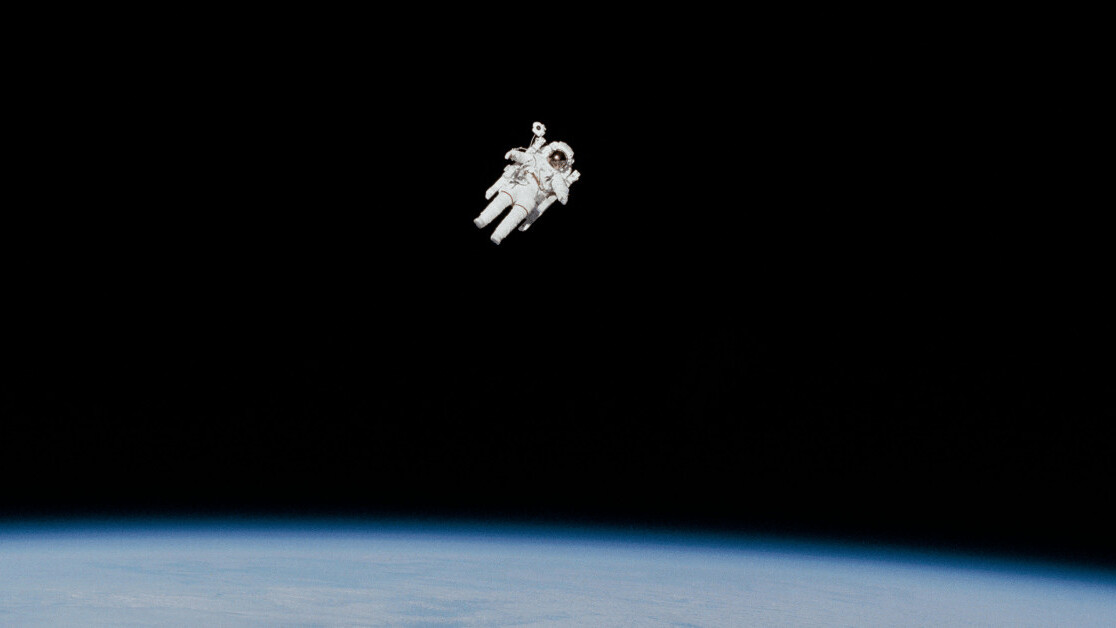

His top of choice is, predictably, a Basquiat tee. Musk hoists them both up, the Japanese billionaire and the Basquiat shirt, as ambassadors for his space colonization company, SpaceX. Maezawa, who may be spending up to $250 million for the tickets, will be the first civilian sent beyond low Earth orbit; he and the SpaceX Big Falcon Rocket crew will be the first humans to make the journey since 1972. One billionaire on the shoulders of another, their smiles glowing, their arms outstretched, their bodies linked like a human caterpillar of capital. This is the ladder to the moon.

Musk’s first luxury lunar cruise is set to embark in 2023. In the meantime, Maezawa will be assembling his entourage. At Musk’s TED Talk-style press conference in September, 2018, Maezawa stated his intention to travel with a group of “top artists” working in sculpture, painting, architecture, photography, music, and fashion design. Casting tech company announcements as lectures is one way these businessmen fashion themselves as thought leaders.

And Maezawa does have big ideas for the journey, which has essentially become a vehicle for his art world aspirations: terrestrial capitalist as lunar curator. The website for the proposed art project, #dearMoon, proffers the usual clichés of imagination, wonder, and awe that outer space is supposed to invoke. Maezawa believes that once artists see the moon, their art (and subsequently the world) will be forever changed by the vision made possible by adventure capitalism. The art bubble and the space boom have been brought together, two moneymaking mills whose egomaniacal premises rarely trickle down to aesthetic or material change.

What is most ambitious about the project is not the world-changing vision that it most likely will not unleash but, rather, the merging of art, space, and tourism. The lunar tourism industry banks on the long-standing appeal of visiting supposedly uninhabited, pristine geographies.

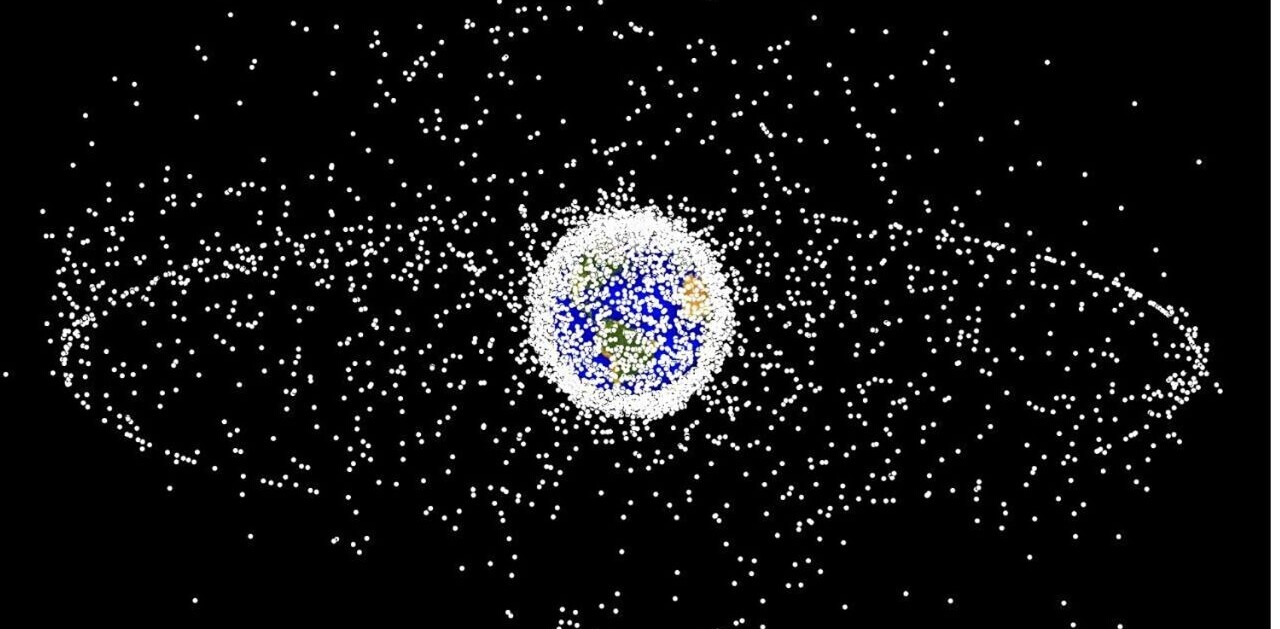

While exoticism once required a background of native peoples, the lunar cruise ratchets up the isolation of seagoing ships and promises a perfected frontier, one emptied of any pesky human life — except those who can pay to visit. Richard Branson (worth $5.1 billion) is selling tickets to “amateur astronauts” for $250,000 each, though when they will be able to use those tickets remains unclear. Jeff Bezos, who is worth more than 30 times what Branson is, spends a billion dollars a year on his own Blue Origin program, which aims not only to put people in space but also to send all their stuff with them. (Those Amazon delivery drones were just the beginning.) These so-called pioneers do not desire an empty frontier so much as one yet to be tapped by entrepreneurial capital.

Spaceport America, located, auspiciously, outside Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, operates similarly. Ostensibly the world’s first purpose-built commercial spaceport, where Branson and Musk can tinker with their rockets, the facility is better described as an empty tourist attraction meant to enthrall the scattered visitors with dreams of space living. But this port in the middle of the desert is as close as most of those people will ever get to space.

Despite all the chatter about our looming cosmic escape — convenient during these times of ever-escalating planetary catastrophe — space travel, let alone colonization, may only be made possible by the megarich. Right now, even billionaires like Maezawa can’t afford to live there. They can only access a more intense vacation experience from behind a rocket window. Musk might have half-convinced himself that he will see Mars colonization in his lifetime — he definitely sees himself as an (if not the) engine of the technological future — but below that lofty guiding star is the base drive for profit. Elon Musk is a tool. And he is making outer space a luxury brand.

Not entirely unlike the way that collectors transform art objects into must-have mansion decor, Musk and his ilk are distorting our understanding of outer space as an alien ecosystem into something simply awaiting human consumption. Tourists often destroy the places they visit en masse, because it’s not the places they care about so much as the experience of being in them. And a large part of that experience is the promise of accessing the out-of-reach, of having the power to traverse boundaries and then return again to the safely regulated and convenient places of origin. All of the adventure of this frontier-hopping is fueled by unsustainable fantasies. Spaceport America is empty. Big Falcon Rocket is hollow. The moon is still an inhospitable alien rock.

We can’t let billionaires hoard all the beauty; we can’t let ourselves believe that everything they have is beautiful. A field trip with a billionaire and his artist friends, that uses so much of the earth’s resources, is not an inspiring image of how the future — on Earth or in space — might be. Under Musk and the competing tech barons, space has become a gimmick. Up for sale is a one-way ticket not from earth’s crises but rather from our ability to imagine different forms of life. Instead of a place for genuine inquiry into our collective future, space has become something else: the promise of profit. Outer space is now a scam.

This article was originally published by Lou Cornum on How We Get To Next. You can read it here.

TNW Conference 2019 is coming! Check out our glorious new location, inspiring line-up of speakers and activities, and how to be a part of this annual tech bonanza by clicking here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.