Earlier this year at Mobile World Congress 2016, Google showcased a demo of a robot that uses selfies to readily draw artsy sketches of your face with a stunning accuracy in a matter of minutes. And while this might seem impressive, Google’s robot is neither the first, nor the only one out there that knows how to hold a brush.

In fact, back in 2011 experimental artist Patrick Tresset presented his own drawing machine – named ‘Paul’ – that drew portraits in a style strongly resembling that of Google’s pet project.

More recently, we’ve seen an algorithm that uses deep learning to transform ordinary photos into fine art as well as a computer program that can recreate the works of Rembrandt.

With all this artistic talent around it’s no surprise to hear there’s now an art prize just for robots with hefty $100,000 prize pool to boot.

The rules of RobotArt – as it’s called – are simple: build a robot that can draw autonomously (or with very limited assistance from humans), let it paint, and may the “artist” with the best art work win.

At present, RobotArt is running its first ever edition and more than 15 teams from universities around the globe have already entered their own machines in the race.

What’s particularly compelling about RobotArt’s inaugural contest is that a significant chunk of these robots produce pieces that bear little to no resemblance to each other. While portraits dominate the canvases, the computer-made art in RobotArt exhibits an admirable variety of styles and genres with works ranging from abstract, to painterly, to representational.

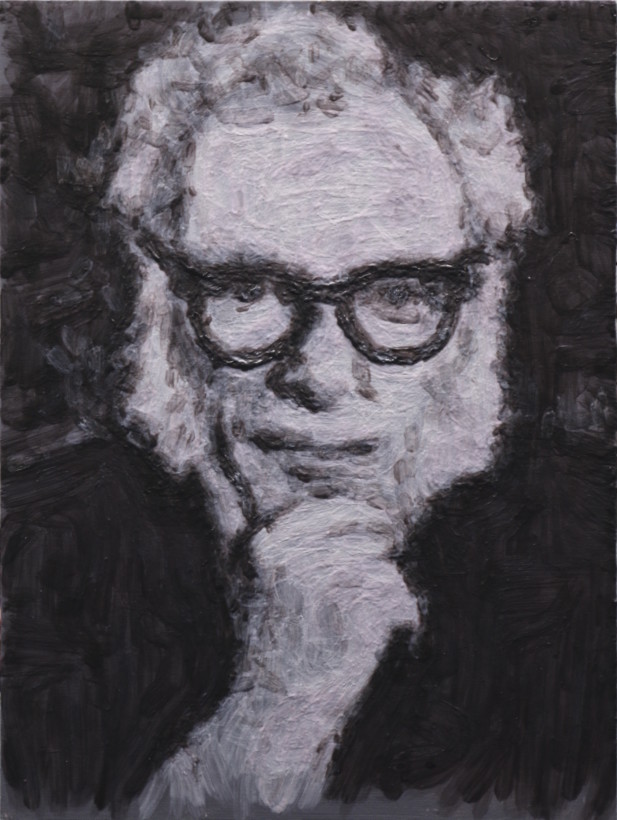

Take for instance the cloudPainter – built by artist Pindar Van Arman from George Washington University – and the e-David – developed by Oliver Deussen and Thomas Lindemeier from the University of Konstanz in Germany.

While both robots take part in the contest with portrait submissions, the idiosyncrasies of their respective works could not diverge from each other more.

Disregarding the obvious differences between color and black and white painting, the robots use two completely different styles of painting. In comparison to the cloudPainter’s rather scattered, truncated and square strokes, the e-David paints with strokes that appear much more wavy, elongated and curvy.

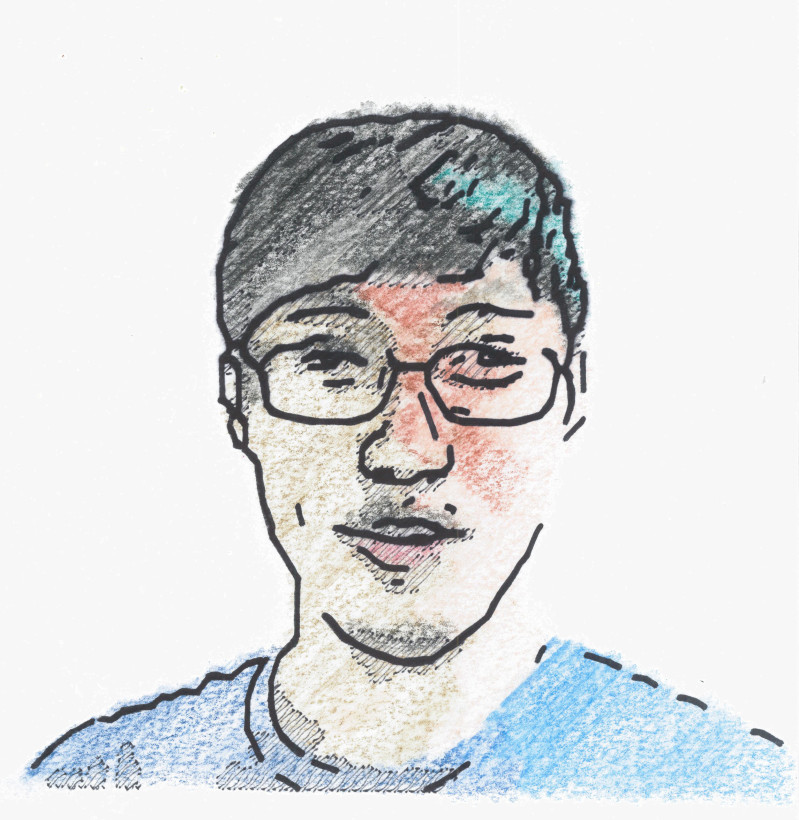

The diversity of styles between the machines becomes even more striking, when we compare the works of the cloudPainter and the e-David to the Pixobot‘s pixel art portraits and the cartoonish approach to painting the Robot Artist takes.

Whereas most of RobotArt’s contestants prefer painting portraits, other robots like University of Manitoba’s Picassnake and Brera Academy’s NoRAA (short for Non-Representational Art Automata) specialize in abstract painting.

The magic behind the artistry of the Picassnake and the NoRAA has to do with how the robots generate concepts for their pieces.

The Picassnake, for example, paints pictures from music. Once loaded with a song, the robot will generate unique movements – corresponding to the music that plays – and paint them onto the canvas.

On the other hand, the NoRAA was designed to be able to interpret its surroundings and use that to create its artwork.

Despite the differences in approach and style, what makes the Picassnake and the NoRAA similar is that both of these robots will generate images based on random parameters they receive from the physical world and not according to input from an actual human being.

For now, the quality of the works the autonomous machines can produce varies significantly from robot to robot. Part of the reason for this is that most of the robots were built with different (often rather experimental) technologies – some more functional than others.

But quality is not what we should zoom in on when we’re judging the work of these robots, because quality will likely improve as the technologies evolve. What’s more monumental here is the abundant variety of styles, genres and concepts these robots are already displaying.

True, neither of the pieces in this year’s RobotArt come across as particularly novel and original, but once engineers succeed in combining the various functionalities and features of these different robots – this might all change.

If originality is a matter of merging old concepts into new ideas, then robots too must be capable of producing truly original art.

And, frankly, this possibility genuinely thrills me. Because regardless of who wins RobotArt this year, I remain convinced that the golden days of computer-generated art are yet ahead of us.

Until then, you can vote for this year’s best computer-generated art work at RobotArt’s website. The contest will be open to public voting until May 10. Winners will be announced on May 15.

They say every generation has its own prodigies and – while it’s still a long shot – RobotArt should teach us something: the world’s next great artist might be a robot.

Image credit: RobotArt

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.