Does it make sense to put a voice assistant in your microwave? Amazon, the leader in smart speakers and voice assistants, seemed to be convinced that it does when it introduced the $60 AmazonBasics Microwave in September.

This week, the first reviews of the device came out, and while I’m not an avid reader of gadget reviews, I was interested to see what impression Amazon’s new venture would create. I found TechCrunch’s profile of the Amazon microwave, aptly written by Sarah Perez, an interesting read.

Beyond exploring the pros and cons of the device itself, Perez’s experience with the Alexa-powered microwave shows that the developers of AI assistants have yet to understand the limits and capabilities of voice assistants and the correct way to integrate digital assistants into physical devices.

This is important since Amazon has considered the microwave oven as a demo of its board and API that will enable other manufacturers to pair Alexa with their appliances.

The difference between smart speakers and smart home appliances

When confined in the Echo smart speaker, there’s no ambiguity over how to interact with Alexa. Users know that they should call the assistant’s name followed by the command. This works for setting timers, turning the lights on and off, playing music and other functionality that don’t require complex, multi-step interactions.

But what happens when you try to accomplish a task that requires multiple steps, some of which you must perform yourself? The microwave provides a very interesting example. Everyone knows that Alexa won’t put the food in the oven or take it out for you, two obviously important steps in using the microwave.

However, we absently expect Alexa to know that we are interacting with the microwave oven and to process our commands in that context. After all, isn’t it powered by artificial intelligence?

But Alexa has no idea that your commands are related to the microwave and requires you to use keywords such as “microwave” or “reheat” or “defrost” to make it understand that you want to make a modification to the microwave.

That’s why, as Perez shows, we might confuse the assistant by giving commands such as “Alexa, two minutes” (instead of “Alexa, microwave for two minutes”) or “Alexa, add 30 seconds” (instead of “Alexa, add 30 seconds to the microwave”).

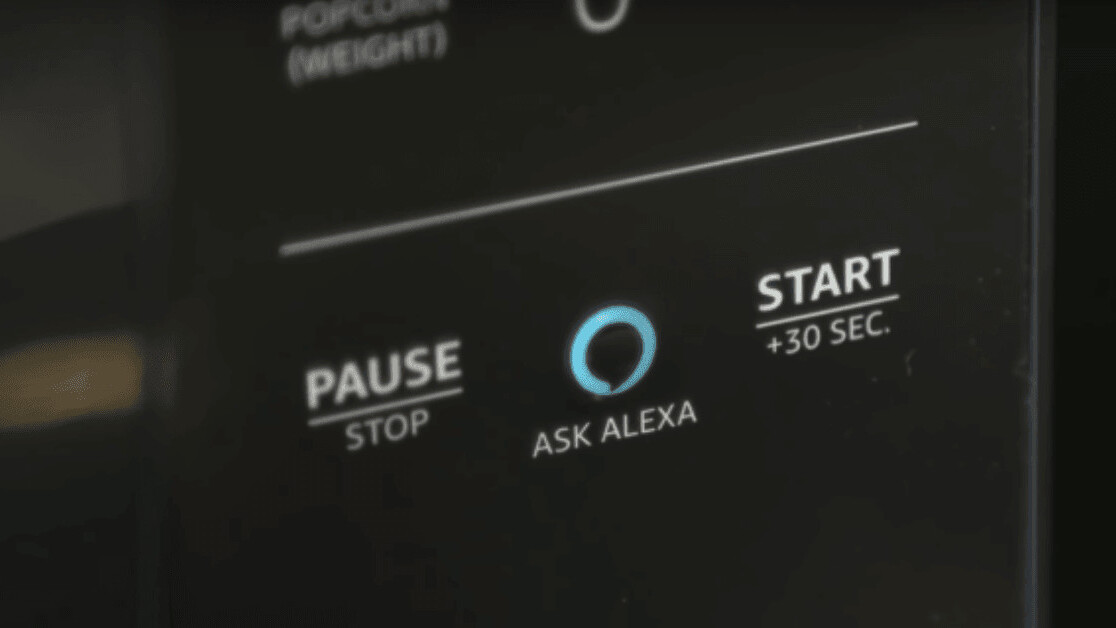

Amazon has tried to work around this problem with an “Ask Alexa” button on the front panel of the microwave oven. When pressing the button, you don’t need to include “Alexa” or other keywords in your command. It’ll understand that whatever command you’ll give will be related to the functionalities of the microwave oven. So for instance, you can just press the button and say “two minutes” instead of saying “Alexa, add two minutes to the microwave.”

But the command can break the uniformity of commands you give to Alexa. Consequently, you can easily become confused and absently include the keywords when pressing the button, or forget them when not pressing it. Perez shows this very well in her review of the Amazon’s microwave oven.

What’s the problem?

Unfortunately (or fortunately), Alexa doesn’t follow you around the house (yet) and unless you explicitly state your intentions, it can’t figure out the hidden meaning behind your words. But why do we expect it to have a general understanding of the context of our commands?

Alexa and other AI assistants are able to process voice commands thanks to advances in natural language processing (NLP), the branch of AI that enables computing devices to make sense of human-written and -spoken language.

While it might come as granted to most of us today, the improvement in NLP is a huge step for the human-computer interaction space, which was previously defined by rigid and clear-cut user interfaces.

So we absently expect a technology that is sophisticated enough to understand the language of humans to also be able to understand the context of those commands, especially when it has a human name. After all, if Alexa was a real human, she would clearly know what we meant when we said “Add two minutes” shortly after we told her to fire up the microwave.

Arthur C. Clarke has famously said, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

But as we have discussed in these pages, there’s nothing magical about AI assistants. The artificial intelligence that powers Alexa and other digital assistants has a very shallow understanding of human language.

Likewise, it has no understanding of the environment it’s in, including the rooms in your house, and the objects in those rooms, or the people who live in the house. No matter how natural or smart Alexa may sound, it is powered by narrow AI, which has distinct limits. It can’t relate facts to each other and fill the gaps where there’s missing information.

How do you fix Alexa?

A very simple fix would be to give the Amazon microwave an assistant of its own, with a unique name, say “Micro.” Then users wouldn’t have to remember long commands. And for the device, there would be no question as to what you mean when you say “Micro, add two minutes.” There would be no need to add an “Ask Alexa” button and require users to learn two types of commands.

The problem with this approach is that you’ll soon have another assistant for your oven, another for your dishwasher, your washing machine, coffee maker and a dozen other appliances in your home. I think this is something we could adapt to, but at first glance, it might sound a bit silly.

But calling a computer by a human-sounding name was the stuff of sci-fi movies a few decades ago. It’s now an inherent part of our daily lives.

Another solution is to give Alexa more context about your home. While limited at thinking in the abstract or forming a general understanding of their surrounding world, AI agents are still very good at processing sensor information. As a rule of thumb, the more data points you give to an AI system, the better it will become at predicting and correlating information.

For instance, if you equip the Alexa microwave oven with a motion sensor and eye tracking technology, Alexa would be able to understand that when you’re staring at the microwave and saying “Alexa, add two minutes,” it should probably add two minutes to the microwave oven’s timer.

This would provide a much more natural experience compared to the “Ask Alexa” button. When you’re staring at the microwave, you expect the person you’re talking with to understand that your instructions are directed at the microwave. When you’re staring elsewhere or are in another room, you will explicitly tell the person that you’re giving an instruction about the microwave.

The advantage of this approach would enable users to stick to Alexa for all their tasks while also simplifying commands. One of the downsides would be the costs. Packing the microwave with motion and eye tracking sensors would probably double its price. But the greater disadvantage would be the privacy risk you would incur if you gave Alexa even more information about your home and living habits.

The security rules and laws surrounding smart homes and the internet of things are still being developed, and IoT devices have accounted for their fair share of security and privacy disasters in the past years.

So, we’ll have to ask ourselves: Do we want Alexa to be smarter, or do we like it just as stupid as it is? That’s something that both developers and consumers will have to figure out as the IoT space develops and finds its way into more domains.

This story is republished from TechTalks, the blog that explores how technology is solving problems… and creating new ones. Like them on Facebook here and follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.