Uber’s been let off the hook by prosecutors in a case involving one of the company’s autonomous test cars that fatally struck a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona last year, reports Reuters. However, the back-up driver behind the wheel will likely be referred to local police for further investigation, and that could potentially see him face charges of vehicular manslaughter for the accidental killing of Elaine Herzberg.

The news should serve to advance our thinking on one of the biggest questions we’ve had for years about self-driving vehicles: who is at fault when a self-driving car gets in an accident? We might be a bit closer to the answer than a few years ago, but we don’t yet have the entire rulebook to decide who to blame in such instances.

The notion of liability in such incidents has been discussed in articles dating back to 2013. The following year, John Villasenor wrote in The Atlantic that “manufacturers of autonomous vehicle technologies aren’t really so different from manufacturers in other areas. They have the same basic obligations to offer products that are safe and that work as described during the marketing and sales process, and they have the same set of legal exposures if they fail to do so.”

Describing how we deal with accidents involving traditional cars, Villasenor pointed to vehicular issues that could be traced back to automakers’ negligence or manufacturing defects – in which case the company that produced the car could be held responsible.

Now, consider The Economist’s breakdown of what went wrong in the Elaine Herzberg case, based on the report from the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

You can read the entire explanation here; it boils down to a system design failure, in which the car’s perception module got confused and didn’t correctly classify the object in front of it as a pedestrian. Next, the automated braking system didn’t prevent the collision, and instead required the human operator behind the wheel to hit the brakes.

The driver, Rafaela Vasquez, was allegedly watching a TV show on her phone at the time, and failed to notice Herzberg in time to stop the car from barreling into her. While it seems like this is squarely on Vasquez, consider the fact that Yavapai County Attorney’s Office, which examined the case, did not explain why it didn’t find Uber liable for the accident.

It’s worth noting that this case – in which the vehicle made a mistake, required the human driver to take action, and the driver failed to do so – involved a test vehicle, which means the technology hasn’t yet been proven to work without fault, and hasn’t been made available for use to the general public.

Now, consider a real-world scenario. Based on events as recent as yesterday, we know that if you tell car owners their vehicles can drive themselves, some of them will put that technology to the test by risking their lives. There have been numerous instances, dating back at least as far as mid-2016, of people sleeping in the driver’s seat of their Teslas while in motion on public roads.

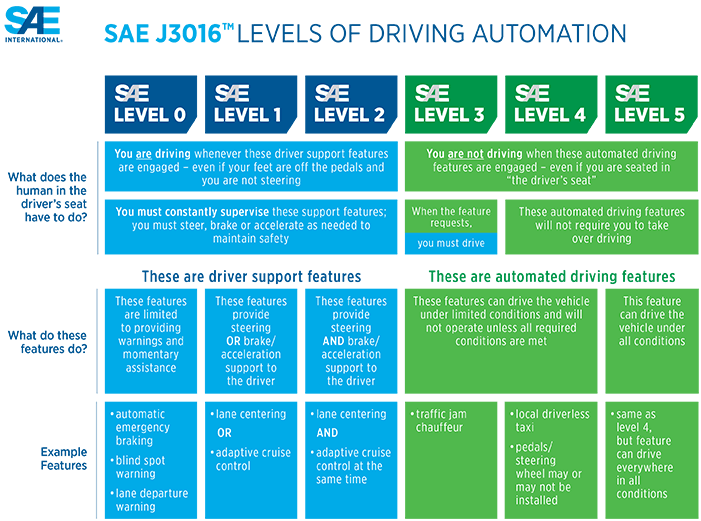

So should we worry about driverless cars getting us in trouble en masse when they become widely available? Probably not. The accidents we’ve seen thus far have, naturally, involved test vehicles, which are close to what’s known as Level 5 Autonomy – but not quite.

Ideally, humans shouldn’t have to lift a finger when riding a self-driving vehicle. And not to defend, Vasquez, but they also shouldn’t have to hit the brakes within a moment’s notice if an autonomous system fails to do so at the very last moment – that’s not how people learn to drive. That also leaves room for error, and in a way, it defeats the purpose of driverless vehicle technology.

Level 5 Autonomy implies that vehicles should support fully automated driving, and not require human intervention during the course of a trip. To attain that sort of hands-off reliability, you need sophisticated sensors for vehicles to detect obstacles, as well as automated systems trained on millions miles of test roads to fine-tune how these vehicles will react in every possible scenario.

Additionally, these vehicles could also benefit from V2X systems (vehicle-to-everything communications, which is an umbrella term for systems that let vehicles talk to other vehicles, traffic infrastructure, toll booths, and more) to receive information about potential dangers and driving conditions beyond their line-of-sight. While all these technologies are in the works and being tested in earnest, we simply aren’t there yet.

Before self-driving cars take over our roads, we’ve got a lot more work to do in terms of perfecting the technologies that will drive them, drawing up and enforcing safety standards for autonomous vehicles, and setting realistic expectations for how this mode of transportation will work. Without all that, we won’t be able to protect ourselves from our own mistakes.

TNW Conference 2019 is coming! Check out our glorious new location, inspiring line-up of speakers and activities, and how to be a part of this annual tech extravaganza by clicking here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.