Business ideas that are truly unique, innovative, and new are nearly impossible to come up with. So when a company hits it big on an certain concept, it’s always interesting to probe into the past and see if they were really the first to give it a shake. Usually they are not. Companies that succeed are often preceded by companies that tried to do the same thing, or something quite similar, and failed.

There is perhaps no better example of that than Groupon, a company that has exploded into relevance, and is now somewhat mired in pre-IPO jitters. There is a veritable graveyard of technology companies that tried the group buying shtick, only to wind up bankrupt. Even more interesting, is that a number of clones that Groupon spawned, due to its success, will also fail. The road to Groupon is paved with dead companies, and in the future, assuming that Groupon doesn’t implode, the company will walk over the bodies of firms that wanted to be just like it.

Group buying is not new. That ‘tipping point’ that all deals on Groupon contain is not their invention, but the crux of how herd-buying works: Tell a store that you can promise 100 customers (whatever the benchmark is set to), and they offer up a fat discount. Now, Groupon managed to take an old concept and make it hugely lucrative, something that the group buying firms of the first dot-com bubble failed to do, but its core product is hardly groundbreaking.

We’re going to take a look at three companies that tried to make group buying a go in the nineties. TNW would like to extend a special thanks to Pud for his excellent book that sparked the idea for this post.

Mercata

If you ever wanted to find a company that embodied, perfectly, the phrase ‘dot bomb,’ Mercata is an excellent choice.

The company cancelled its IPO one day, and went out of business the next. In the process of dying, which really seemed to start from day one for Mercata, the company set fire to 89 million dollars. 100 employees lost their jobs, and of course, stock options.

Mercata was a group buying system, but a very annoying one. Instead of simply presenting consumers a deal, or perhaps set of deals that updated (Groupon!), users of Mercata (not that there were ever that many) would tell the site what items they were interested in buying, and at what price. Mercata could then talk to manufacturers and hopefully score the deal.

Of course, it flopped like a pancake.

ZoHo

No, not that Zoho. ZoHo, the lame one, was Mercata, roughly, but for businesses. It, like Mercata, died.

Pud, in his excellent little book, described the flaws in Zoho as such:

ZoHo was a hyped-up “e-procurement” business, where hotels could team up and buy products in bulk. You know, like those little shampoos. Ice buckets. Probably those paper ribbon things that say “sanitized for your protection.”

One of the hurdles faced by these companies [TNW: this is what Groupon managed to get away with] is that they charged of a transaction fee or percentage to the SELLER. Not only that, but it likely wouldn’t integrate into the seller’s exisiting ERP system.

ZoHo: “Print” the order, fill it out, ship it, and then enter the order number back into the Zoho system.

Seller: How much extra work is that? Print the order? Fuck you.

To make matters worse, they had a lot of competition.

Yeah, they didn’t make it. Their domain and name live on though in the ZoHo that you know, which has effectively scrubbed the company’s existence from the Internet. Call it luck.

OnlineChoice

OnlineChoice (.com, naturally) was a group buying site for things such as long distance calling (ha), electricity, and other such items.

The idea was to take a bunch of demand, and use it to score discounts. Do you see the flaw? Discounts can’t run that deep on the services that they were trying to push. Therefore, they had to try to get people to sign up just to save, wait for it, 0-5%.

Pud, take it home:

Sounds familiar? It is… it’s basically another group buying fiasco but this time with fewer products and less savings. And this one cost investors around $20 million and employed seventy people. Seventy people. This business, this WEBSITE, could have run by a SCRIPT. Zero employees. Okay, MAYBE a couple of people to broker the deals with suppliers.

And that is the story of how $20 million dollars was shot up in smoke.

Looking into the future, it’s hard not to see a whole new crop of dead group buying (or group coupon, which breaks down to the same thing in most cases) companies scattered around the world. Groupon’s massive initial success contained the sort of explosive growth that spawns me-too companies everywhere. All around the world, and especially in my hometown of Chicago, group buying sites are popping up with nearly annoying alacrity. We’re the Groupon for new moms! We’re the Groupon for startups! We’re the Groupon of Groupon! And so forth. They won’t last, or at least most of them won’t.

Hell, now that everyone has chewed over Groupon’s S1 form that it filed to go public, some people don’t think that Groupon will make it. Groupon has raised over one billion dollars. It had better make it.

The company has to address its massive losses, which could be mitigated, how it will continue to differentiate itself in the face of relentless competition (those pesky clones), and of course, manage customer fatigue. Groupon has much going its way, but it is by no way ‘home.’ Not with its current habit of setting fire to cash.

Groupon seems to know that it has to grow up. It’s admission that it would redo parts of its S1 tells something positive about the company, that its culture might be in the clouds, but that it can focus and wear a suit when it is required. Although, the culture of Groupon could be its saving grace, provided that it can use its zaniness to keep its users active and engaged.

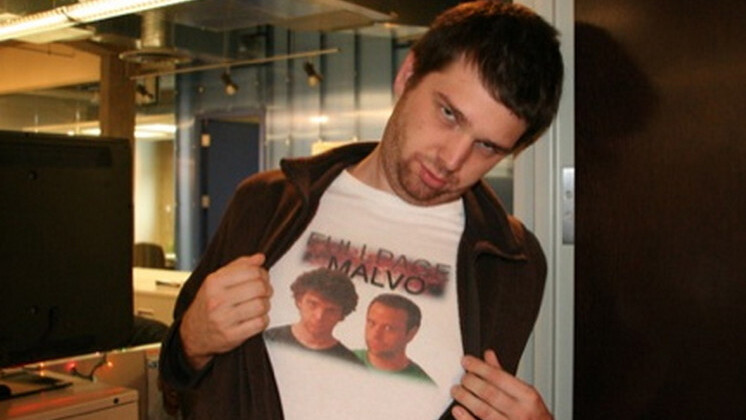

This sort of thing keeps users on board.

But if Groupon can preserve what makes it special, and learn to keep its spending in control, and use its IPO money to get into the black, we might have had the pleasure of watching the birth of a Great American Company. But group buying companies have come and gone since the early days of the Internet, and Groupon is not immune to the plagues of the past.

When you contemplate how many similar companies have died, and thus made room for Groupon to take over the world in a year’s time, you almost want Groupon to win, just so that the cycle can end. The market has made it clear: Group buying sites will always exist. Perhaps Groupon will be the startup that lived.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.