As an American who recently moved to Asia, one of the most challenging adjustments were my mobile habits; especially how I communicate.

In the US, my phone had zero messaging apps. None. Not even Snapchat. All my communication was done through Apple’s iMessage service. I moved to Tokyo in June, and now Line is one of the most used apps on my iPhone 5s.

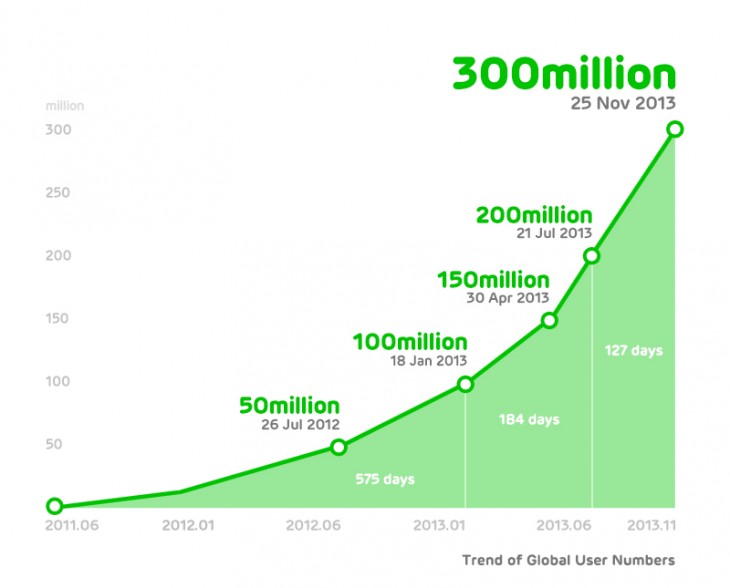

Line is the messaging app that recently broke 300 million registered users and brought in $99.9 million in net sales for Q3. Add to that KakaoTalk — Korea’s largest messaging app with game revenue of over $300 million in the first half of the year — Tencent (WeChat’s parent company) reporting revenue of $630 million for Q3, and WhatsApp with over $350 million paying a dollar a year, and the messaging app space seems like a lucrative one.

Living in the US, messaging apps did nothing for me. Now that I live in Asia, I see things differently. I believe in messaging apps because I rely on them, but I don’t see them as ‘the next Instagram or Snapchat’.

Mobile Market differences

The US phone market is SMS reliant. Japan is the opposite. Everything here happens through Line. When exchanging contact information people give their Line IDs first. Communication with friends, colleagues, random people I meet, even other iPhone owners… everything is through Line.

Living in Asia, we frequently connect with those in surrounding countries. When I first moved, I would offer my email address or iMessage as primary contact, but that confused people. A lot of people. At first I thought I was committing a cultural faux pas, but quickly I learned the standard is: anyone living in Japan shares their Line ID, people who live in Korea share their KakaoTalk ID, China is WeChat, and Southeast Asian residents may be any of the previous three, Facebook or WhatsApp. It’s like an unspoken rule that everyone in Asia knows, so most people in Asia use multiple messaging apps.

Being immersed in this messaging app phenomenon is why I doubt any new messaging apps will overtake the current bunch on market share. There’s no room for anything new, as the most popular messaging apps fulfill all communication needs. Private communication? Check. Group chat? Check. Photo, video, and VoIP? Yup, they’re all there and more.

Features aside, the major apps have already hit critical mass. Unless some mind-blowing function like teleportation or the ability to download food is integrated, I really don’t see hundreds of millions of users moving on to a new app.

Line’s rise in Japan

Take the Line story, for example. Line, wasn’t an overnight success and there is good reason for that. Line’s biggest marketshare is in Japan. Japan’s smartphone market really began growing in 2011 — some four years after the US — and analysts have found a near-150 percent rise in smartphone adoption between 2011 and 2013.

Of the 127 million people in Japan, smartphone ownership finally passed 50 million users in August, but things are developing rapidly. Japan overtook the US as the biggest spenders on apps only this week, and the market is potentially hugely lucrative for makers of popular apps.

This market shift also affected Japan’s text-based communication.

Text-based communication in Japan is very different from the US and other parts of the world. Japanese telecoms have advanced emailing systems, where carrier-issued email addresses are attached to every mobile number. The email system functionally operates like SMS: simple, free and unlimited. SMS in Japan is charged per text, so before mass market smartphone adoption, text communication was done by keitai meru (cell phone mail).

With the rise of smartphones, apps quickly became popular. As users got used to beautiful, gesture-based UIs, text-based cell phone email no longer fulfilled their needs. That’s when Line started gaining serious traction. People go where their friends are and Line happened to be in the right place, at the right time.

Line changed Japanese mobile communication.

And it’s easy to see why people quickly adopted Line. An Internet connection gives users free unlimited voice calls, unlimited free messaging, unlimited instant photo sharing, group chats and video communication. The interface is cute and Line is very easy to use, but, most importantly, it offered a solution to the ‘pay for all and everything’ Japanese telecom model — and Line disrupted the Japanese mobile industry.

Cultural differences

Asians — and particularly the Japanese — have always been big on emoji. Emoji was popular in its basic form before we in the US started jailbreaking our iPhones to add smiling poo, slow-moving farm animals, and beer mugs to express ourselves.

I don’t know how the Japanese did it, but they figured out ways to show emotion through keypad symbols on flip phones. iPhone emoji doesn’t render on Android (and vice versa) so the Japanese continued and some even still continue using symbol combinations like:

- >< to express embarrassment

- (^__^) for joy

- ^( ̄□ ̄#) as anger, etc., etc.

Enter Line stickers (or as we call them in Japan, stamps), when the flip phone to smartphone shift started. In a market that didn’t have a dominant mobile OS, Line’s cross-platform stickers made sense to replace text-based emoji. It also secured major brand partners — including Sanrio, Disney and Namco-Bandai — and turned familiar, beloved and nostalgic characters into stickers.

Line stickers aren’t novelty items or after thoughts. It’s part of the company’s strategy. Line has rollout calendars, timelines and milestones for stickers to keep users interested, engaged and addicted. There are ‘Sticker Directors’ at Line, who oversee the planning, production and direction of sticker content. (Line is hiring one now, if you’re interested.)

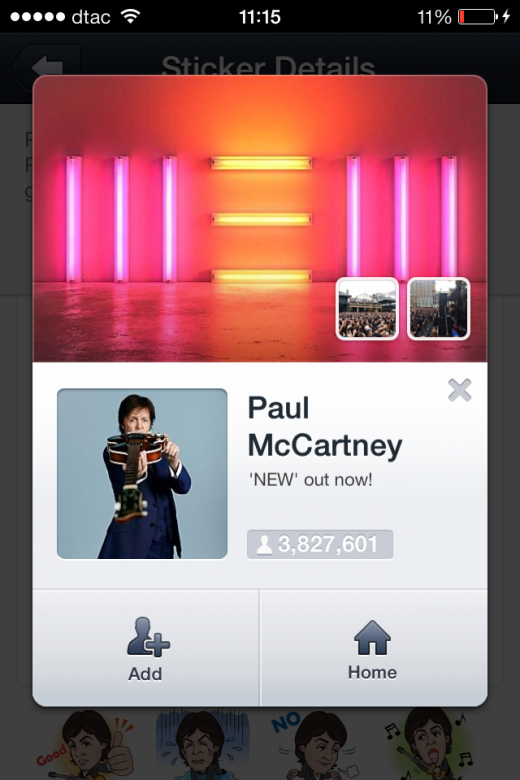

Stickers, are also part of Line’s business model. Line limits advertising on its platform (mainly) to sponsored stickers. The flow of sticker advertising goes something like this:

- Advertisers pay Line to let them offer stickers, which are usually branded.

- Line users are offered the chance to download these free, limited edition stickers from advertisers.

- Stickers are usable only after the user adds the advertiser as a contact.

- Once the users has opted-in to allow the account, advertisers can message their Line ‘friends’ with advertisements, but even then, the number of messages an advertiser can send are limited.

This system allows advertisers to clock up an audience of millions of users quickly, as Beatles singer Sir Paul McCartney has done.

Line has a no spamming policy that is strictly enforced and creates a win-win for users and advertisers. Users get free stickers with minimal spam, advertisers get to ‘market’ on the largest platform in Japan. Line makes money. Users are happy. Advertisers are happy. Everyone is happy; everyone is staying put on Line.

Aside from sticker monetization, Line has a robust social gaming platform. The Japanese have always been about gaming (hi, Nintendo, Sega and Playstation), so, of course mobile, gaming has exploded. Add the social gaming layer and people are even more addicted. Think of mobile games in Japan as addictive as Candy Crush. Except there are variations. Many variations. Currently there are 43 in the App Store and Google Play Store, with over 200 million downloads as of September.

Line’s business model works. In September, Line was the number two publisher in monthly revenue (excluding games for iOS) and first for Google Play — so it’s safe to assume the company made a whole lot of money since, unlike WhatsApp, Line is free to download for life.

The top mobile publishers by monthly revenue (excluding games) for Google Play, basically sums up the dominance of messaging apps in Asia.

American companies like Disney, Microsoft, Condé Nast, and others are on the top 10 mobile publishers for iOS. Compared to that, Google Play’s main money makers are from Asian countries. Of the 10, three are messaging apps Line (Japan), Kakao Talk (South Korea), and WhatsApp (US-based but biggest market share in markets like Southeast Asia).

Mass Adoption

Line was born as a direct reaction to the big earth quake in March of 2011. Telephone lines broke down for days while the Internet, mobile Web and cell phone mail (keitai meru) worked the entire time. Engineers at NHN (Line’s Korean parent company) needed a way to communicate with each other, and thus created Line. Because of the disruption to traditional communication, the digital divide — old vs. young, tech savvy vs. tech illiterate — became evident in Japan after the quake, and Line was launched to the public in June of 2011.

One of the greatest product features on Line is the simplicity of the on-boarding process. Users register on Line with their mobile phone numbers. Line then scans through the phone’s address book for other users, and automatically adds them as a contact. This feature may sound creepy but makes it so easy for those not so technically savvy to quickly find and communicate with people you know.

Line’s success is a combination of factors. It came into the outdated Japanese telecom market during a time of need. It became the ubiquitous, free communication tool, during the smartphone shift. The company is business savvy and understands its market and users.

NHN has had a presence in Japan since 2011 and also owns Livedoor, a popular Internet portal. Like Line, Livedoor’s success also happened over the course of several years.

Too late for more messaging apps?

Analysts, tech blogs and news outlets are focusing increasing attention on the growth and prominence of messaging apps. Just like Line, the messaging apps we see and read about, entered the space during Asia’s mobile disruption, and a lot of Asian countries are still going through change.

Asia in 2013 is much like the US was in 2007. We are reliving the US smartphone revolution, and the software-to-app movement is starting. The stats we see are simply surfacing the current scale of mobile in Asia. So when I read about how messaging apps are the ‘next big thing’, I can’t help but shake my head.

Don’t get me wrong, I get how messaging apps may look like the next big thing, but it’s too late for a new messaging app to enter and gain market share at this point.

As for the American market specifically, messaging apps are not a fit. Simply, because there is no need. Which is also why I firmly believe that neither Line, KakaoTalk or WeChat will see the same success in the US as they do in their respective dominant markets. That’s particularly true after Instagram launched its Direct messaging system.

So, to all the talented developers, hungry entrepreneurs and VCs with loads of money: find something else to build. You are tardy to the messaging app party.

Headline image via Africa Studio / Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.