Japan-based mobile messaging company Line raised eyebrows in May when it revealed that it made $17 million from selling stickers during the first quarter of 2013. Last year stickers were all but unknown in the West, but today you will find rich emoticon-like stickers on Path, Facebook, Viber and a range of other services beyond the first messaging apps that helped popularize them in Asia.

What are stickers and why are people buying them?

Stickers are larger-scale emoticons which are primarily used for instant messaging (IM) chats. They are popular among some, particularly in Asia, because they help convey emotion, and are more visual than blocks of text. Stickers typically come in packs of up to a dozen, most of which are free to download and use, but some services charge $1/$2 for premium packs — which may be customized for brands, products or limited edition events.

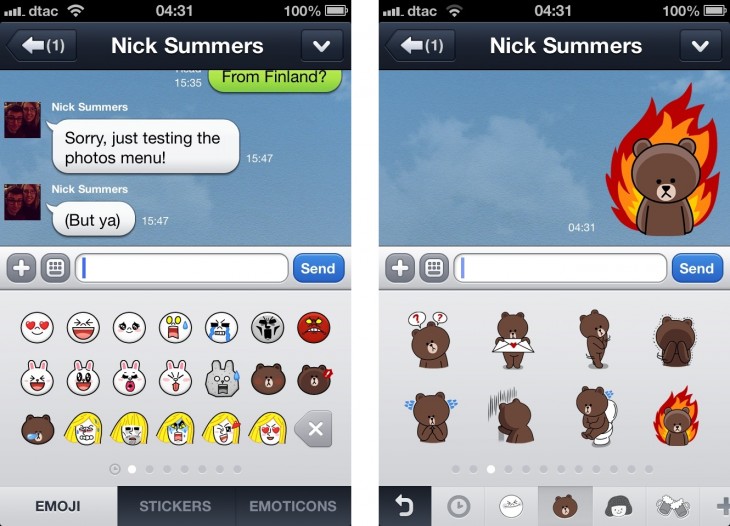

Once downloaded or bought, they appear as an option in the text box, and are published when pressed. Here’s me using a sticker on Line, the free call and text messaging app, which claims to have more than 250 stickers.

If you’re not familiar with mobile messaging apps like Line — which has more than 150 million registered users, most of whom are in Asia — then your first experience of stickers may come via Facebook, which recently added them to its Web service having already rolled them out on mobile. You can find them in the Facebook Messenger apps for iOS and Android, or when you send a private message via the Web or regular Facebook apps.

Here’s how Facebook describes them:

Stickers are different than emoticons. They’re detailed illustrations of characters with personality. Sending stickers is a way to share how you’re feeling with your friends.

Facebook’s selection of stickers is comparatively small at this early point, but it already includes unique content such as a set dedicated to Mark Zuckerberg’s dog Beast. Here he is below paired with one of his stickers — the photo on the right is from Beast’s own Facebook Page, of course:

In the beginning

The origin of stickers goes back to post-tsunami Japan in 2011 when Korea’s top Internet company — Naver — began developing Line in Japan. The company used data-based calls and text messages because they worked better than regular calls and text messages on the country’s strained telecom networks, which had been affected by the tragedy.

Naver opted against focusing on Korea because it felt the market was too challenging, mainly due to the dominance of Kakao Talk, which is said to be installed on more than 90 percent of Korea’s smartphones today.

Line was the service that first pioneered emoticons, and its rise in Japan — where it is more used than Facebook, Twitter and other social networks — helped turn stickers into a communication tool for users and a lucrative business for companies.

Stickers are a mix of cartoons and Japanese smiley-like ‘emojis‘. Both are popular in Japan — the home of anime — and when brought together they gave Japanese smartphone owners an addictive new way to communicate emotions and feelings with quirkiness. Not to mention that the challenge to accumulate your own personal collection appealed too.

Also — crucially — using stickers means users spend less time tapping out words on a phone, making communication easier and more rapid. Stickers are as much about saving time and effort as they about being expressive; particularly given that Japanese Kanji is tricky to input digitally.

It isn’t clear whether emoticons drove Line’s early popularity in Japan, or whether the emoticons grew as the app became more popular, but both downloads of the app and the profile of the characters featured in Line’s sticker collections grew at pace, with the latter developing into cult figures.

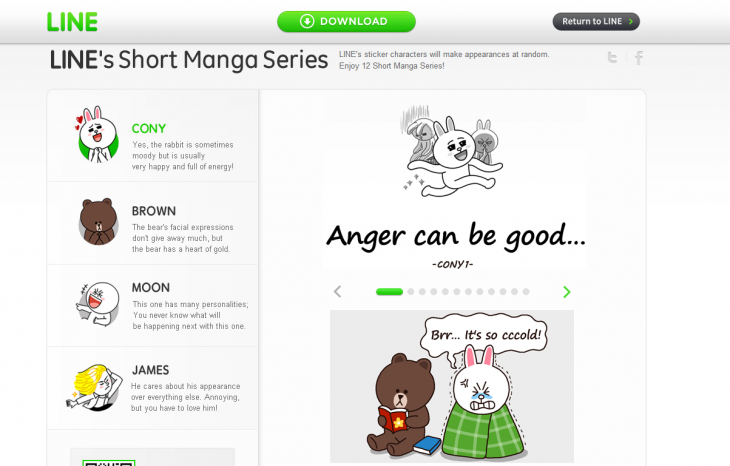

Today, Line’s characters — which include ‘Brown’ the bear and ‘Cony’ the rabbit above — are threatening to become Angry Birds-like in merchandising terms, as this excerpt of a post blog from Pepperdine University’s Business School explains:

As part of the marketing strategy, Line characters are everywhere in Japan now. Stuffed toys, books, stationery, capsule toy, anime on TV, in stores, on billboards – you can’t miss them. Even celebrities are getting in on the action. For $1.99, you can purchase the famous Korean rapper PSY’s Line stickers depicting his popular hit, ‘Gangnam Style’ and the well-known horse-riding dance moves that have won fans all over the world.

Going worldwide

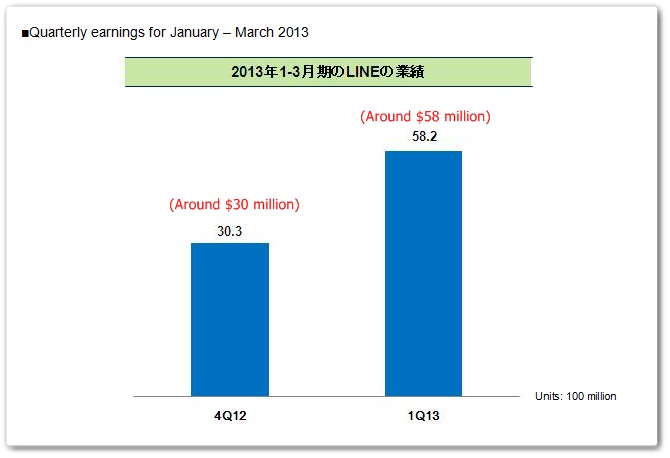

Line says that 80 percent of its total Q1 2013 revenue — which reached $58 million — came from Japan. The company doesn’t break out its revenue for the rest of the world by geography or via sticker sales, but it is assumed that the bulk of the non-Japanese sticker revenue came from users across Asia.

That’s likely down to cultural similarities with Japan, but it remains entirely possible that stickers are being used — and potentially bought — by sizable numbers in Europe, the US and other regions. A recent report from the Wall Street Journal certainly suggests usage of stickers is global, while Facebook’s recent introduction of stickers is sure to help raise awareness of them outside of Asia.

(It’s worth noting that Line’s revenue compares very favorably to other messaging firms that are either not monetizing, in the early stages of exploring models or have adopted low-friction/low-revenue approaches. WhatsApp, for example. charges each user a flat $1 per user subscription fee.)

More than just cute items, stickers have proven to be strategic too.

Thailand and Taiwan have both developed into two of Line’s strongest international markets because users there found that the app’s stickers saved them time writing messages — non-English languages can be complicated to write using a smartphone. Line has amassed market-leading positions in both markets despite advertising and extensive promotional campaigns from rivals like China’s WeChat and Kakao Talk.

The idea of time-saving stickers is a concept that Facebook used when it rolled out a ‘thumbs up’ icon to its messaging service.

The idea of time-saving stickers is a concept that Facebook used when it rolled out a ‘thumbs up’ icon to its messaging service.

The aim is to make confirmations as simple as tapping the Like button. Rather than having to type out ‘ok’, ‘got it’, ‘yes’ or similar, you just use the sticker.

Despite success in Asia, it appears likely that the appeal of stickers is different in Western markets, where Romanic alphabets are better supported on smartphones and there is less of an emoji/cartoon culture.

Since Line, Kakao Talk and WeChat are still in the early stages of building their international user bases it is too early to really know how they and their sticker sets are being received outside of Asia.

There are non-Asian examples though, aside from Facebook.

Private social network Path added stickers and messaging in March of this year, having already gained traction in Asia, though the US is its main market.

Speaking back when the Asia-inspired Path 3.0 update landed, founder Dave Morin told us that stickers are not just for decoration but were implemented because they let users communicate better than text and in a more emotional way.

Path’s approach to stickers is more premium and design-based than the comic book-style of Line. Its sticker are ‘unique pieces of work’ selected from artists worldwide and exhibited in Path exclusively, though of course they retain an emoticon-like look.

The company has never revealed details of its revenue, but it did tell TechCrunch that it made more money during the 24 hours after it launched stickers than it had done during any day previously. Without details of revenue based on geography, it is impossible to know if that spike was down to the fast-growing but enthusiast minority in Asia or whether US-based users shelled out for Path stickers.

The business model

Stickers are just one line of revenue used by Line, Kakao Talk and others, which includes in-app games, other virtual items, business accounts and more. Focusing back on stickers, the companies make money from them in a number of ways.

Many stickers are available for free, or are free for a limited period before becoming paid-for. Stickers that tap into a brand or celebrities are most likely to be paid for given that they already have consumer appeal and could be considered collectible.

A number of services, including Facebook and Hike in India, have initially made all of their sets free after introducing stickers, likely as a prelude to introducing paid packs once their communities are using stickers and they have unique content that can be priced at a premium rate.

Line users can also buy stickers for their friends, perhaps for a special occasion or a spontaneous act of kindness. Transactions are made using the service’s virtual currency — something Kakao Talk and others also offer — although the gifting feature was recently removed from the Line iOS app as it breached Apple’s terms of service.

More than a mobile chat app, Line is blossoming into a platform and that’s reflected by the fact that many of its sticker characters crop up in its social games and linked apps (such as Line Camera — which allows images like Brown and Cony to be added to photos), giving its brand and platform closer links.

In addition to making money by selling stickers to users, the model used by Line and others is two-sided and companies can pay to have their own sticker packs. It may appeal to those seeking a subtle marketing approach, to experiment with new platforms or explore ways of building brand awareness and engagement.

Based on figures from its Taiwanese business, Line charges around US$35,000 (TW$1 million) to allow 8 stickers to be available for download for one month; users have up to six months to use them before they disappear. It’s not clear if that charge covers the design and development of the stickers, or whether that is additional, but that price is entry level and many firms spend much more on a campaign.

To date, stickers have been used in Asia to promote new films, music albums, drinks, airlines and more. Developing a pack of stickers certainly represents an interesting complement to existing advertising and marketing platforms, but it’s not territory that many firms in the West might cross just yet.

Stickers also help drive merchandising sales as well as consumer awareness of the messaging services that they are available on.

As mentioned earlier, Line is seeing much success with its merchandising. The characters within its sticker packs have been made into cartoons, TV ads, clothing and plush toys. All of that helps drive visibility of the Line brand and provide additional income streams.

Here, for example, is how Line’s characters were used to help promote the app in Spain, where it claims to have had success. The country was seen as a strategic market due to its position within Europe, Spanish language (Line is also targeting Latin America) and the fact that rival WhatsApp had a dominant market share.

Another ad in Spain uses the celebrity attachment — this time it’s Korean music star PSY — alongside the ‘cute’ characters. Similar adverts have been used in other markets, some tapping into local celebrities and others also using the characters.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljC-RYy5gNE

Becoming the next emoticon

Though Line is seeing financial and brand success thanks in some part to stickers, it is by no means certain that its efforts, and those of Path, Kakao Talk and others, can be replicated by simply any company. Engaged users and a unique offering look like being two of the keys that have seen the use of stickers take off.

Undoubtedly stickers are becoming more popular among new audiences — but it remains to be seen if those outside of Japan and the rest of Asia are willing to pay to express themselves beyond what words can already convey.

Certainly, Facebook will be a good barometer for measuring that. The company is not known for moving quickly — its reputation for copying apps and features once they have shown traction is testament to its conservative nature — but if it begins selling sticker packers, which seems like a logical move in time, then it might suggest consumers are ready to spend; while the phenomenon might really take off outside of Asia given Facebook’s 1 billion monthly active users worldwide.

Stickers began as features on a handful of messaging services that are popular in Asia but, as these services continue to increase their presence worldwide and Asian messaging business models gain more attention, we can surely expect stickers to become as synonymous with messaging as the humble smiley.

Image of Line plush toys and stickers via Line

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.