In the past few years, smartphone manufacturers have started paying more attention to the optics they use on their smartphone, using wider apertures for better low light performance. That’s awesome, but as a photographer, I have an ongoing gripe about the marketing buzz around apertures: An aperture tells you little about performance if you don’t know the camera’s sensor size.

As a refresher, all else being equal, wider apertures (a lower number) mean better low light performance and shallower depth of field (more background blur or ‘bokeh’). The problem with smartphone photography is that rarely is everything else equal, sensor size in particular.

I’m going to oversimplify things a bit, but let’s assume two phones are technologically identical except for their aperture or sensor size. If two phones have the same sensor size, the one with the wider aperture will be better. But by the same token, if two phones have the same aperture, the one with the larger sensor will win.

If both of the variables are different, well, things can get pretty messy.

To use an exaggerated example, here’s a photo taken at F1.8 on the Pixel 2.

And here’s a photo taken at F3.5 on a high-end camera with a much larger micro-four thirds sensor.

Despite the ‘wider’ aperture on the Pixel, the micro four-thirds camera has much more blur (and would theoretically perform much better in low light too). That’s because the micro four thirds sensor is capturing more light overall thanks the much larger surface area on the CMOS chip.

To drive the point home, here’s the micro four-thirds camera at F1.8

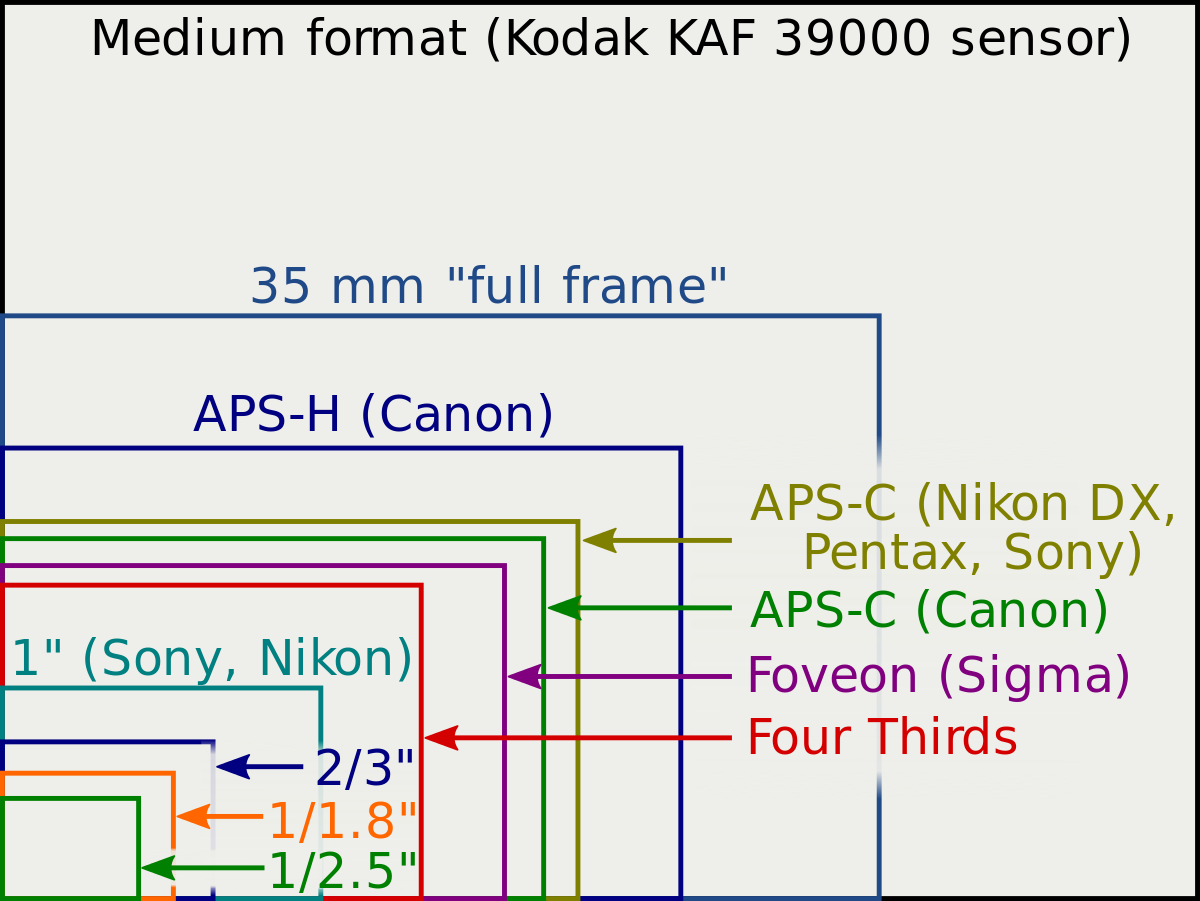

This image compares common sensor sizes for different camera categories. The Pixel 2’s sensor is believed to be 1/2.55,” or a teensy bit smaller than the smallest sensor on that image. You can see the dramatic size difference.

I bring this all up because it’s far too common for smartphone manufacturers to claim a wide aperture while obscuring information on the sensor size. You can generally deduce this based off of other information like the pixel pitch and field of view, but that’s more complicated than it should be.

Take the LG V30, whose F1.6 aperture was the largest on a smartphone at the time of its announcement, and was heavily promoted in marketing materials. It was supposed to be a significant update over the V20’s F1.8, and I was all excited for bokehliscious night-time photos. That is, until I realized LG conspicuous didn’t mention the V30’s sensor size. There was a reason for that: the LG V30 is using a smaller sensor (1/3″) than the V20 (1/2.6″), largely negating the aperture advantage.

This isn’t to say the actual lens and sensor technology aren’t better on the V30 – it’s absolutely a better camera overall – but making a show of a larger aperture is disingenuous when the sensor is smaller. Worse, smaller sensors tend to have inferior dynamic range, which can’t be fixed by simply increasing the aperture.

That’s not to say making sensors smaller is always a bad thing either. The Pixel 2 also made a similar move (from a 1/2.3″ sensor to a 1/2.55″ one), but it gets a pass because in addition to a wider aperture (F1.8 vs F2.0), Google also added optical image stabilization for better low light performance, and seems to be using better sensor tech overall.

Again, the problem is when marketing heavily focuses on a larger aperture without mentioning the sensor has been made smaller. Sometimes a large enough aperture can overcome a smaller sensor in terms of low light performance, but it’s up to manufacturers to be upfront about how big that jump actually is.

So why are do smartphone manufacturers keep using small sensors? Thinness, of course. Larger sensors require larger lenses, and often require larger components for features like optical image stabilization.

As a side note, that’s part of the reason some manufacturers have taken to using dual camera systems where one sensor is RGB and the other monochrome. These systems generally use some of the smallest sensors for primary rear cameras, thus allowing for thinner frames (the Essential Phone, for instance, avoids a camera hump by using two 1/3″ sensors). In theory, these phones can get away with having tiny sensors by combining detail from the two images, but in practice, they’re rarely as good as just having one really big chip.

Of course, there’s so much more to smartphone photography than sensor size and aperture. The technology behind the sensor, the quality of the lens, the software processing, HDR algorithms, optical image stabilization, and now even fancy tricks like computational bokeh.

Point is, don’t judge a phone’s camera purely by its specs – the results matter more than anything else. And to smartphone manufacturers: stop flaunting your wider apertures if you’re going to shrink the sensors at the same time.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.