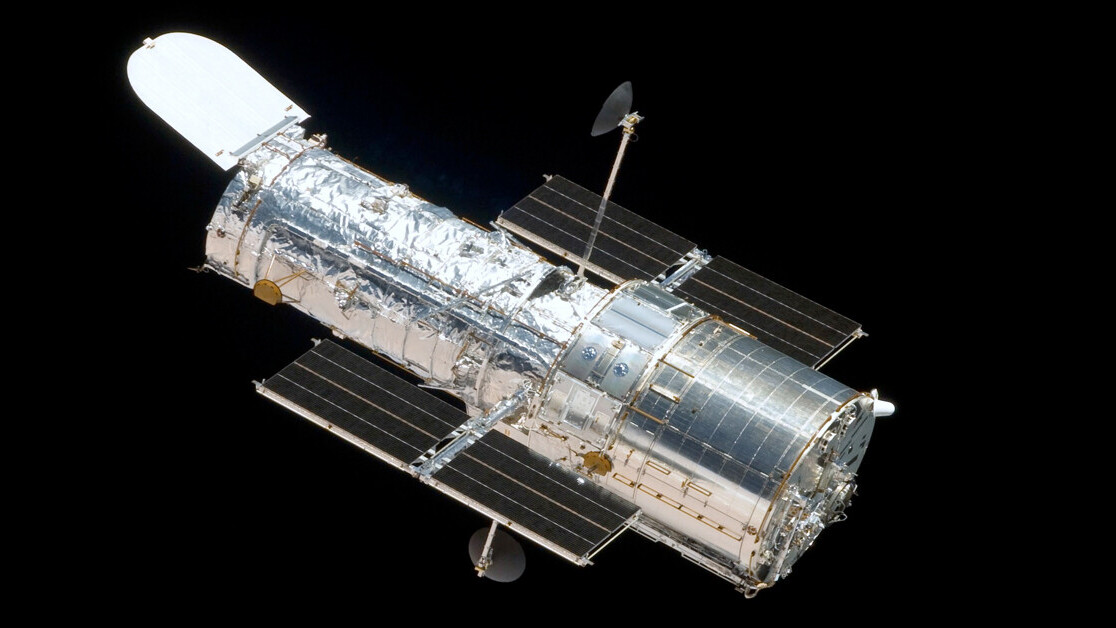

The Hubble Space Telescope set its sights on a total lunar eclipse, using the Moon as a mirror to study Earth. Here’s how it could help us find life on other worlds.

The Hubble Space Telescope has imaged a total lunar eclipse, becoming the first space telescope to ever image such an event. This also marked the first time that a total lunar eclipse has been thoroughly examined in ultraviolet light, as well as the first time ultraviolet (UV) light was seen from space after passing through the atmosphere of our homeworld.

The technique used to measure ozone in the atmosphere of the Earth could be adapted to allow astronomers to study exoplanets like Earth orbiting other stars.

[Read: Ultraviolet light gives astronomers new clues on mysterious stellar eruptions]

In the coming years, a new generation of telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope, will journey into space. Some of these instruments will be able to peer into the atmospheres of terrestrial (small rocky) worlds, revealing their compositions.

It’s kind of like hunting Medusa. Only look at the shield.

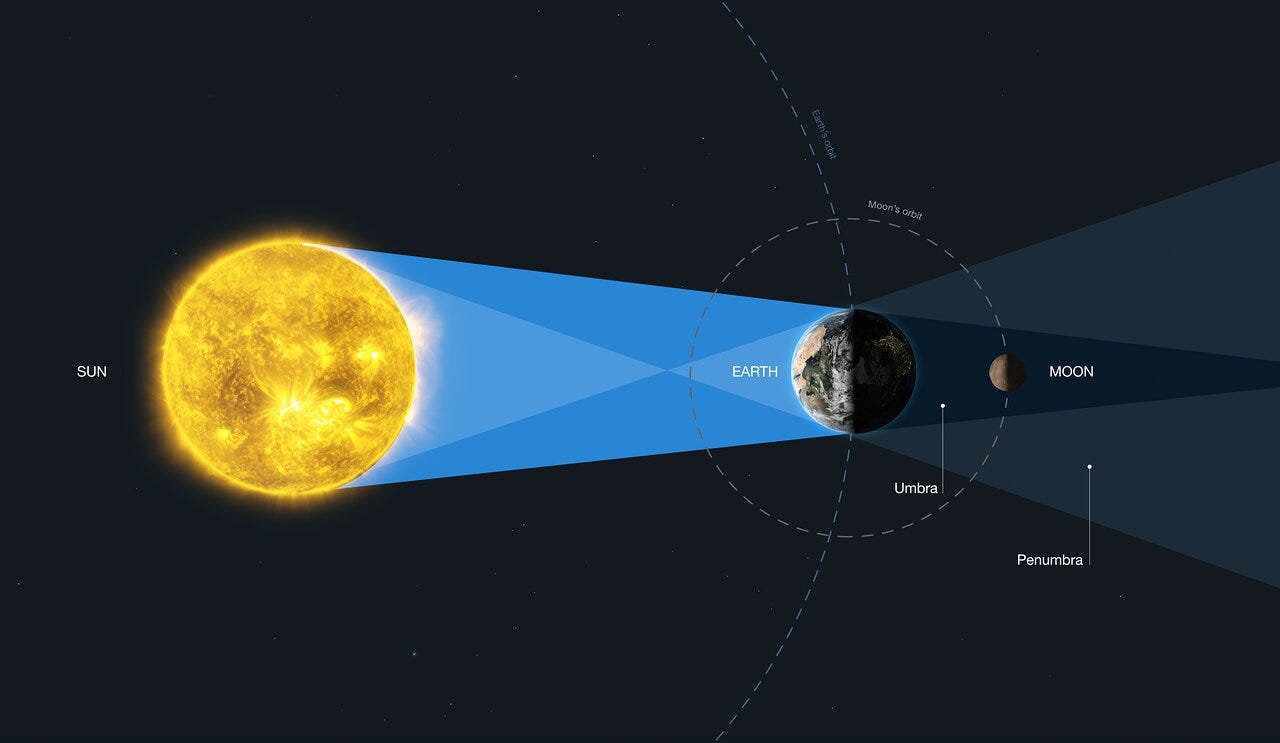

This recent lunar eclipse provided astronomers a chance to test an observational technique on a familiar target — our own homeworld. The precise alignment of the Sun, Earth, and Moon during a total eclipse is similar to the arrangement of exoplanets as they transit — pass “in front of” — their star as seen from the Earth.

The Earth is far too bright to be directly imaged by Hubble. Therefore, astronomers looked at light, reflected off the Moon, which had passed through the atmosphere of Earth.

Prior to the eclipse, the Moon shone brightly. Engineers directed Hubble to direct its sights on one small region of the lunar surface, carefully tracking its motion relative to the orbiting observatory.

Observations revealed the presence of ozone (O3) in the atmosphere of our homeworld. Although hardly a shocking revelation in itself, the technique used in this measurement may be applied to worlds orbiting other stars.

“O3 is photochemically produced from O2, a product of the dominant metabolism on Earth today, and it will be sought in future observations as critical evidence for life on exoplanets. Ground-based observations of lunar eclipses have provided the Earth’s transmission spectrum at optical and near-IR wavelengths, but the strongest O3 signatures are in the near-UV,” researchers described in The Astronomical Journal.

Ozone signatures had previously been detected during eclipses using ground-based telescopes. However, ultraviolet light is largely blocked by the atmosphere of our world, making this the strongest detection of the atmospheric molecule ever recorded.

Photosynthesis drives the production of ozone in the atmosphere of ancient Earth, building up high levels of oxygen and a significant ozone layer on our world. By 600 million years ago, atmospheric ozone had built up to the point where the surface of the Earth became shielded from the deleterious effect of ultraviolet light from the Sun, allowing lifeforms to crawl from the ancient oceans onto the barren land for the first time.

“Finding ozone in the spectrum of an exo-Earth would be significant because it is a photochemical byproduct of molecular oxygen, which is a byproduct of life,” Allison Youngblood of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, lead researcher on the Hubble observations, stated.

In addition to ozone, researchers also tested the technique, looking for signs of oxygen, methane, carbon monoxide, and water.

Getting in the ozone

There could be as many as a billion Earth-like planets scattered throughout the Milky Way galaxy. High concentrations of oxygen and ozone in our own atmosphere provide chemical evidence of biological processes occurring in our world.

As astronomers view exoplanets passing between their parent star and Earth, a tiny sliver of light from the star passes through the planetary atmosphere. By breaking that light up into its constituent colors, astronomers are on the verge of being able to determine the chemical makeup of the alien atmospheres. The most advanced space telescopes ever built will spend hours training their sights on distant atmospheres of alien worlds.

“A sad spectacle. If they be inhabited, what a scope for misery and folly. If they be not inhabited, what a waste of space.” — Thomas Carlyle

Hubble has peered into the atmospheres of gas giants similar to Jupiter in the past. But, terrestrial planets are much smaller, with far thinner atmospheres, making astronomers wait for a new generation of space telescopes to carry out observations of these tiny worlds.

“One of NASA’s major goals is to identify planets that could support life. But how would we know a habitable or an uninhabited planet if we saw one? What would they look like with the techniques that astronomers have at their disposal for characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets? That’s why it’s important to develop models of Earth’s spectrum as a template for categorizing atmospheres on extrasolar planets,” Youngblood explained.

Chemical processes suggest that life elsewhere is likely to produce ozone on terrestrial worlds orbiting distant stars. By looking for molecules related to life on Earth, investigators hope to find evidence for alien life for the first time. Unlike methods aimed at finding electronic signals from intelligent lifeforms, searching for the telltale gases of life in alien atmospheres might allow us to find life far too primitive to develop radio technology.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.