Over the past few years, hardly anything in the world of the Internet has gathered as much attention as music. From the death of terrestrial radio to the delayed worldwide releases of sites such as Spotify, we’ve run the gamut of ideas, choices and opportunities. Why has it been so difficult? It turns out that a service you’ve likely used before, Last.fm, has some unique insight into the ecosystem that is online radio.

Let’s go back a few years. It’s somewhere in the 1980’s and my dad is working at a radio station called Star 101 in Orlando, Florida. He had done radio for as long as I could remember, so I grew up in and around radio stations and developing a fascination with them.

When Did it Hit You?

If memory serves me correctly, I was 11 years old (which would put this at 1987, if I remember how to do math) and there was a song by Genesis called Tonight, Tonight, Tonight. I was being the annoying boss’ kid, hanging out in the studio with the on-air DJ, but he was kind and let me pick a song that I wanted to hear. I played Genesis.

To my surprise, a few seconds into the song, the phone rang (or more appropriately, a strobe light flashed telling us that there was a phone call). The caller on the other end of the line told us how it was such an amazing song and they were so glad that we played it. For me, this was the moment of my addiction.

Growing up, we taped songs off of the radio. We recorded compilations of these poorly-recorded songs for boyfriends and girlfriends. We passed them around and found new favorites while reliving old ones. We never looked at what we did as wrong, we were just sharing great music.

Along the way, though, something happened. Blame the artists, blame the labels or whomever you want, but the industry that we grew up on, the industry that we loved had changed. Instead of doing a favor to friends, we were now criminals. Our actions hadn’t changed, but the enforcement of them certainly did. That which we today see as purity was suddenly gone, replaced with accusations, lawsuits and jail time.

Going Digital

It was around here, in 2001, that I left radio myself. I still had a deep love for what it could be, but I certainly had no love for what it had become.

Fast forward a few years and we’ve seen CD’s, CD recorders, MP3, Napster, the iPod, DRM and the entire surge of the digital age of music. I remember the sinking feeling that I had in my stomach when I heard the words “terrestrial radio is dead” for the first time.

The Beginning

Around this same time, give or take a couple of years, a computer science project by Richard Jones was being programmed. Dubbed Audioscrobbler, it was a way for people to do charting and collaborative filtering. In essence, it was giving you the ability to create your own radio station. Jones released the API for Audioscrobbler and it was (arguably) most successfully adopted by Last.fm for use with the site’s music player.

Last.fm’s space wasn’t so crowded back then. In the following years we’d see the introduction of eMusic, the re-rise of Napster and most recently offerings from Spotify, Rdio and more. Somehow, amid the rise of the competitors, Last.fm had lost a bit of its shine. Then, the company did what many argued would be the silver bullet to its success — it implemented a paywall for its mobile functions.

I’m a fan of radio. Well, more specifically I’m a fan of not necessarily knowing the exact song that’s going to come up next. While terrestrial radio formats such as the Jack-FM stations have tried to replicate the experience that Last.fm and its counterparts provide, they’ve never done so very well specifically because they’re based on charts that have been put together by a mass, rather than a specific person.

For me, Last.fm had provided something that I wanted for a long time. It was the return of the mix tape. It offered what seemed to me to be better curation than Pandora and the ability to look at my scrobbles was interesting (but more on that later). Admittedly, I was about to play the funeral dirge for Last.fm as well, but then I had a phone call.

The Future

I spoke at length with Matthew Hawn of Last.fm. Hawn’s an American guy, living in the UK, with a long history behind him. He started working for Macworld magazine years ago, moved on to working with record lables and joined the Last.fm staff only a few months ago. In a surprisingly candid interview, Hawn tells me what Last.fm means to him, where the service has gone wrong and most importantly what’s coming next.

The first thing that I had to bring up with Hawn was the seeming failure of the mobile apps. Since slightly before the paywall had gone into effect, and up to the date of the phone call, I hadn’t been able to use the mobile app on Android. On iOS it often froze, skipped tracks or just crashed.

“I’ll cop to the rocky start. It’s not been a great experience for people on the mobile side of things.”

Wait…did an executive just admit that something went wrong? Yes, indeed. This interview was looking up already. It continued to do so when Hawn immediately then said that new apps for Android and iOS were coming in the next week. Sure enough, the following week, my Android app updated and it has worked flawlessly ever since the removal of one nagging bug.

So what was the problem? According to Hawn “Putting in a paywall was a fairly extensive change for us. [But I feel that] the value is actually there for a premium service. But it needs to feel premium.”

What’s worth the money? According to Hawn, it comes down to three key areas:

- Listen anywhere, scrobble anywhere

- Recommendations from scrobbling

- Sharing and social

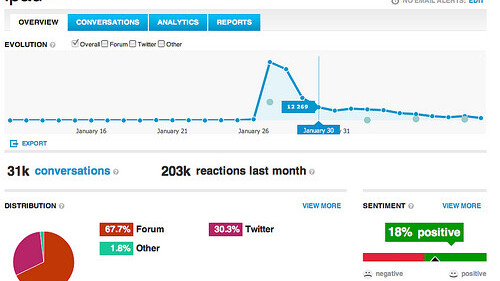

In case you haven’t spotted the theme here, Last.fm is relying heavily on its API and scrobbling in order to push it forward. Seemingly, though, the bet is paying off. Users of Last.fm on Xbox account for higher listenership on any other console or set-top box and that’s just one of the many platforms upon which you can listen and scrobble back to the site.

I asked Hawn where Last.fm was going to go next. After all, staying stagnant after erecting a paywall isn’t a good idea for anyone. There had better be, as Hawn says, the value for a premium service. Would we see Last.fm integrated into cars or other non-traditional spaces for Internet radio? “Automotive is an interesting question because it’s bigger in the US but not elsewhere.”

The Last.fm business model is interesting. In order to survive, it has to have listens. One would think, then, that the subscription model is intended to be the savior of revenue. Hawn states otherwise — “We get paid three ways. Subscription is an important part of revenue, but it’s not the main part.” Of course there’s the advertising, but then there are the scrobbles and API. According to what Hawn seems to feel, if a service such as Rdio wants to be successful, it will use Last.fm data.

“We’re already big data. We have 800 scrobbles per second, and over 50 billion scrobbles since we started.”

That’s a powerful figure, and one that emerging artists are likely going to be paying more attention to as time moves on. Looking at Next Big Sound, a site that shows where people are discovering music, you can see that breakout artist James Blake was discovered via Last.fm far before he was ever played anywhere else. It is this sort of power that Last.fm is hoping to leverage to move itself forward.

Products such as the Festival Finder are also going to be increasingly important. Instead of just looking at a lineup with names that you might not know, Festival Finder gives you a score to show you how likely you are to enjoy the content of the show. All of this, of course, relies on your scrobbling data.

The evolution of Last.fm is as a “musical passport”, says Hawn. “We’ll be in more services to personalize your experience. We’ll be working with more great people.” The hope is that you’ll discover more music via promotion, and this is especially true for live performances. “A phenomenal percentage of Last.fm users go to live gigs.”

While Last.fm is inherently social, Hawn doesn’t want a push of Last.fm into being a social network by current standards. “The social features need to be better”, says Hawn. “We need to make it clearer why we think you should scrobble, why you should share, etcetera. I would like for people to think of us more like a data service, along the lines of Twitter and Foursquare.”

To that end, Hawn states that Last.fm will work with the newest of music services, as well. Of course it doesn’t play well with Pandora, but that fault lies in Pandora’s hands. “We’re going to scrobble things that play on your Android, even from Amazon or the upcoming Google service.”

The entire idea behind scrobbling is that it provides you with a more personalized listening experience. Beyond that, though, Last.fm is interested in how you categorize music. “Tag is more powerful than genre”, says Hawn. “We have input from 40 million experts.”

Admitting that I’ve not used the tagging feature much, Hawn explains its importance. He says that, obviously, the ways in which I’d describe a song are not necessarily the same ways that others would. But when a personal tag becomes overwhelming for a specific song, that tag can then go to a global position, where it will guide the playing of a Last.fm genre by description, rather than a specific name that could be widely argued.

So is Last.fm the return of the mix tape? From where I’m sitting, yes. In a world where we’re moving to make everything more specific, more semantic, Last.fm is replacing the listening habits of your best friend, but still giving you access to them. With nearly 10 years of data and a love for what radio should be, Last.fm’s future is bright. What’s most interesting, though, isn’t necessarily the site itself but what others will do with it.

If you’re a former Last.fm fan, taken aback by the problems of the past, give it another shot. If you’ve not yet seen the magic that scrobbling and tagging can provide, it’s time to give Last.fm a shot. No boombox required.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.