How frequently do you find yourself reaching for your phone or laptop to check your email, Facebook or Twitter, or just to look up something on Google– without thinking, plainly following an impulse?

They say that when you do something often enough, it eventually becomes a habit and many companies nowadays – Facebook, Twitter and Google being just a few of the examples – seem to have built their success around this realization: in order to to truly captivate the user, products must form habits.

This is what serial entrepreneur, teacher at the Stanford Graduate School of Design and instructor here at TNW Academy Nir Eyal specializes in – habits, and, more specifically, how to design habit-forming products. This is also the topic of the amazing talk he gave at TNW Conference last year, his best-selling book Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products as well as the course of the same name that you can find on TNW Academy.

We recently had the pleasure to sit down with Nir and discuss how the ‘Hook’ model works, what makes products addictive and how leading tech companies keep customers coming back.

To start off, what is the ‘Hook’ and how does it work?

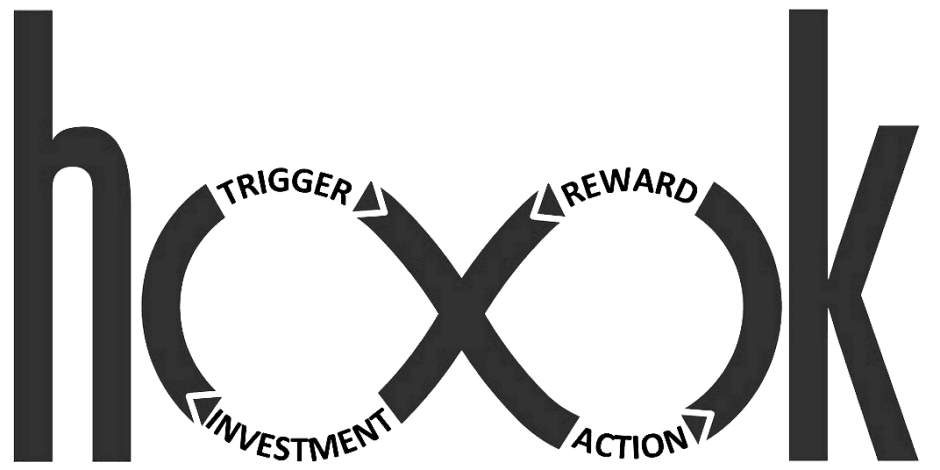

Nir Eyal: In my book, I describe ‘Hooks’ as experiences that connect users’ problems to a company’s product with enough frequency to form a habit. Hooks are in all sorts of products we use with little or no conscious thought. Over time, customers form associations that spark unprompted engagement, in other words, habits. In the four step process I describe in Hooked, I detail how products use hooks to create these powerful associations.

Can you perhaps break down the four parts of the ‘Hook’ for us and give us a few examples?

N.E.: Hooks have four parts: a trigger, an action, a reward, and an investment.

Triggers are things that cue the habit. Whether in the form of an external trigger that tells the user what to do next (such as a ‘click here’ button) or an internal trigger (such as an emotion or routine), a trigger must be present for the habitual behavior to occur.

Over time, users form associations with internal triggers so that no external prompting is needed — they come back on their own out of habit. For example, when we’re lonely, we check Facebook. When we fear losing a moment, we capture it with Instagram. These situations and emotions don’t provide any explicit information for what solution solves our needs, but users eventually form strong connections with products that scratch their emotional itch.

By passing through the four steps of the Hook, users form associations with internal triggers. However, before the habit is formed companies use external prompts to get users to act.

Next comes the ‘Action phase.’ The ‘Action phase’ of the Hook is defined as the simplest action done in anticipation of a reward. When the habit forms, users will take this simple action spontaneously to alleviate the pang of boredom or when missing someone special. Opening the app gives the user what they came for — a bit of relief attained in the easiest way possible.

The next step of the Hook is the variable rewards phase. This is when the user gets what they came for and yet is left wanting more.

This phase of the Hook utilizes the classic work of American psychologist B.F. Skinner who published his research on intermittent reinforcement. Skinner found that when rewards were given variably, the action preceding the reward occurred more frequently. When forming a new habit, products that incorporate a bit of mystery, get us hooked.

For example, Snapchat, the massively popular messaging app used mostly by college students and teenagers, incorporates all sorts of variable rewards that spike curiosity and interest. The ease of sending selfies the sender believes will self-destruct makes sending more, shall we say, ‘interesting,’ pics possible. As is the case with many successful communication services, the variability is in the message itself.

The final phase of the Hook prompts the user to put something into the service to increase the likelihood of using the service in the future. For example, when users add friends, create preferences, or create content they want to save, they are storing value in the platform. Storing value in a service increases its worth the more users engage with it, making it better with use.

Investments also increase the likelihood of users returning by getting them to load the next trigger. For example, sending a message cause the receiver to reply, thus prompting the original sender with an external trigger in the form of a new notification. Loading the next trigger through a user-initiated action sends the user through the Hook once again.

Through successive frequent passes, user preferences are shapes, tastes are formed and habits take hold.

Are there any dangers to the ‘Hook’ model and how can we avoid them?

N.E.: Addictions are always bad, they harm the user. However, habits are different. We have good habits and we have bad habits. I believe that we’re on the precipice of an age where designers can help their users create healthy habits through the technologies they use. By building habit-forming products we can help people live healthier, happier, more connected lives by using habits for good – we just need to understand the deeper psychology behind habits in order to build them.

There are two reasons I wrote Hooked. First, I want to help people build products that create healthy habits. I think there is so much we can do to help our users live happier, healthier, more productive lives, by designing healthy habits. Second, even if you’re not a product designer, you’re still a consumer yourself and it’s important to understand how products change behavior so that you can break the hooks that aren’t serving you in your own life.

Hooked exposes the hidden psychology of all the attention-draining distraction in your life so that you can regain control.

Who is this course for?

N.E.: This seminar is for anyone seeking to understand habit-forming product design. The workshop is tailored to product managers, entrepreneurs, or designers working in all sorts of companies, large or small. Although no previous background is required, attendees will benefit if they come to the course with a product or a business idea in mind.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.