This is the second in our Future Of series, where we analyze and dissect one facet of life that’s been impacted by digital technology. Today, we look at handwriting.

From the ancient scripts of Sumerian 3,000 years before Christ, through the dawn of the Greek alphabet and onto the ballpoint-toting, crossword-puzzling of the 20th century, handwriting has played a massive part in the development of the human race.

Long before Gutenberg arrived on the scene in the fifteenth century with his fancy printing press, people were penning everything from prayers and poems to mantras and memoirs. And everything in between.

Even after the proliferation of print, the humble pen continued to flourish. History owes a lot to the literates who, entirely off their own steam, chose to document the times they lived in. Without people such as Samuel Pepys, there would be huge caverns in our knowledge of major events that happened in relatively recent history.

But over the past couple of decades, there has been a tangible shift away from ink and lead-based inscription, into digital representations of this thing we call language.

I don’t know about you, but I can count the number of times I pick up a pen each month on one hand. Scratch that, three fingers would suffice.

Birthday cards, signatures and perhaps the odd calendar reminder on the front of my fridge – that’s it. Everything else is keyboard- or touchscreen-based.

This posits the question: Is handwriting a dying art?

The pen is mightier than the keyboard

Whenever the old makes way for the new, it’s never a cut-and-dry tag-team switch – transition is the name of the game. Just look at typewriters.

Typewriters evolved in design from the early 19th century and snowballed in popularity before finally reaching a standardized set-up by the start of the 20th century. Electric typewriters were actually already on inventors’ radars in the late 19th century while the mechanical incarnations were still finding their feet and, as such, these were slowly tweaked and developed throughout the 1900s before finally finding a firmer foothold by the 1960s.

However, this wasn’t long before the first fully-fledged computer-style word processors came to pass; and by then, the modern PC-addled age was on the horizon. Whilst we’re on the subject, some people still actually use typewriters. But we digress.

The written word has had a whirlwind century of change. If you want to take things back even further to Gutenberg’s printing press in the 1400s, it’s fair to say that handwriting has fended off a tonne of innovations. It may be in peril but it’s still very much with us – the question is, for how much longer?

You see, the difference between everything in the past 500 years, and now, is that not everyone had a printing press, typewriter or word processor in their home. And not everyone tippy-tapped on their own personal mobile telephone because, well, they didn’t exist.

I was still penning essays at school – and even university, to a degree – in the 1990s, but with the proliferation of PCs, smartphones, tablets and interactive whiteboards, handwriting is in danger of becoming obsolete. You could say the writing’s on the wall.

The state of play

In the US, schoolchildren traditionally learn cursive (joined-up) writing from around the age of eight, but with the introduction of the Common Core State Standards Initiative back in 2010, some reports suggest this has lead to as many as 45 states opting out of teaching cursive by adopting these standards. A recent report in the Washington Post proclaimed:

“The curlicue letters of cursive handwriting, once considered a mainstay of American elementary education, have been slowly disappearing from classrooms for years. Now, with most states adopting new national standards that don’t require such instruction, cursive could soon be eliminated from most public schools.”

Why? Many schools see handwriting as surplus to requirements when there are perfectly good keyboard-enabled computers. But are things really as bad as some reports would have us believe? Is handwriting on the way out?

We touched base with J. Richard Gentry, a researcher, author and lecturer specializing in literacy education, and a columnist at Psychology Today, to get a better idea of where things currently are, and where they may be heading.

“Schools in America seem to be all over the place,” says Gentry. “While more and more schools embrace technology, traditional handwriting instruction may be coming back. I have been surprised to see handwriting getting new attention among researchers and brain scanning techniques are allowing for new ways of researching the issue.”

The importance of handwriting is well-acknowledged in the research fraternity, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect on the school curriculum. Plus, it seems there’s not even a consistent state-wide ‘standard’, let alone a country-wide one.

“In some schools every child has a computer or iPad, while in others there may still be only one computer in the classroom,” continues Gentry.

But what about these ‘Core Standards’ that were brought in a few years back, haven’t they been more-or-less universally adopted?

“While neither handwriting nor spelling gets explicit emphasis in the Common Core Standards, I don’t believe these basic skills have been ditched,” says Gentry. “My understanding is that the North Carolina state legislature recently mandated handwriting instruction, and other states may follow suit. Common Core sometimes sends mixed messages about basic skills. Eighth graders, for example are supposed to ‘spell correctly’. But Common Core doesn’t really ‘spell out’ grade-by-grade expectations for skills such as handwriting and spelling. These basic skills should be a part of the writing and reading curriculum.”

It seems that rather than explicitly saying that cursive handwriting shouldn’t be taught, the Core Standards simply omit to mention it at all. This essentially leaves it up to individual school districts to decide what role cursive plays in the curriculum.

And Gentry is in fact correct about North Carolina – back in April, the state House of Representatives unanimously passed legislation requiring elementary school students to learn cursive handwriting, apparently in direct response to the state’s adoption of the Core standards. And it seems that California, Georgia, Idaho and Massachusetts are following suit.

“Major publishers of handwriting curriculum, such as Zaner-Bloser, offer a balanced approach and recommend about fifteen or twenty minutes a day in the early grades for handwriting instruction,” adds Gentry. “In today’s world, children need both skills. Technology and handwriting are compatible, complementary — both should be taught in school.”

Angela Webb is a former primary head teacher, and is now an independent psychologist and Chairman of the National Handwriting Association (NHA), which has a remit of raising awareness of handwriting as a crucial component of literacy in the UK. We asked her what the current state of play is with schools – is handwriting under real threat?

“In primary and most secondary schools, keyboarding has hardly replaced handwriting at all for class assignments or exams,” she says. “A few adolescents on the Special Needs register get a concession to use a keyboard for public exams. However, this is hard to get. Currently, 50-60% of the primary school day is spent on pen and paper activities, and all public exams are required to be handwritten at secondary AND tertiary level, which is also true of most professional exams, such as accountancy, law and medicine.”

If you’ve been out of school for more than five or ten years, you could’ve been forgiven for assuming that schools across the country were all iPad-enabled digital havens of the 21st century. That’s certainly what I would’ve expected, but it seems that isn’t the case – and handwriting is actually arriving back on the syllabus in some UK secondary schools to combat the scourge of text messaging.

“Most classrooms have a laptop for the teacher and an interactive whiteboard,” continues Webb. “Few have computers for children though – there’s just not enough money. The standard IT provision in primary schools is thirty minutes in total per week for computing skills – touch-typing is not taught. Some secondary schools may have more hardware, but it is usually confined to the IT dept and is not generally available in the classroom.”

This actually turns the whole question on its head. Rather than handwriting being under threat, there’s seemingly scope for greater focus on IT and keyboard skills. But that’s a debate for another day.

Hearing what Webb and Gentry have to say, handwriting is still very much alive and kicking – in the US and UK at least – and any discussions around its imminent demise are greatly exaggerated. But a quick peruse around the Web does reveal reports to the contrary.

In the Washington Post article mentioned earlier, Steve Graham, an education professor at Arizona State University, and an expert on handwriting instruction, isn’t quite so upbeat about the the current status of cursive handwriting.

“The truth is that cursive writing is pretty much gone, except in the adult world for people in their 60s and 70s,” he said, adding that teachers value typing more than the penned word. It seems that any serious argument these days for preserving handwriting centers on tradition rather than practicality.

“What I typically hear for keeping cursive is how nice it is when you receive a beautifully cursive-written letter,” continued Graham. “It’s like a work of art – it’s pretty, but is that a reason for keeping something, given that we do less and less of those kinds of cards anymore?

“When you think about the world in the 1950s, everything was by hand – paper and pencil,” he said. “Right now, it’s a hybrid world.”

A hybrid world indeed.

Convergence

We’re seeing many vestiges of the old analogue world being kept alive in various digital guises, from apps to physical hardware. Here’s a quick look at some of them.

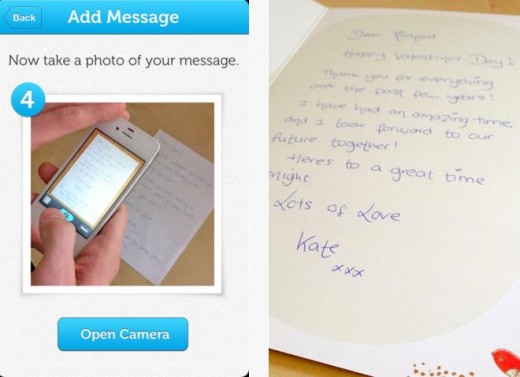

Inkly

Inkly lets you buy and send handwritten greetings cards directly from your iPhone, simply by snapping a photograph of your scribbles from a blank sheet of paper and transposing it onto the card.

“Inkly uses patent-pending image-processing and extraction techniques to make sure the handwritten message looks exactly as you wrote it,” says Lee Hawkins, the London-based Inkly co-founder. “It is so accurate, that the recipient won’t even know the handwritten message is printed. Combined with printing presses and card stock, Inkly cards are printed to the highest possible quality every time.”

It’s an interesting concept for sure – on the one hand it’s preserving the personalized ‘stamp’ that works much better for greetings cards, but it’s also tapping the convenience of smartphones and apps.

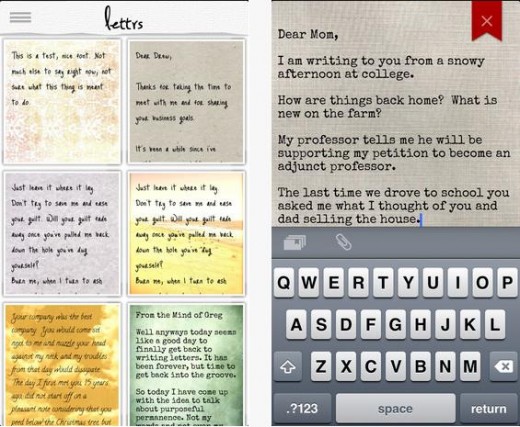

Lettrs

And let’s not forget Lettrs, which turns your PC and iPhone into a personal writing desk, transcriber and post office.

Available for Web and iPhone, Lettrs serves up a virtual writing desk, with a slew of handwriting-esque fonts, typewriter-style lettering and various paper-types to choose from. When you’re done, you can choose to deliver it digitally – email, Twitter, Facebook, or send as a physical letter.

Physical letters are dispatched from Lettrs’ base in the US, so it costs slightly more for non-US users. But, you can also print it out yourself and send if you’re so inclined.

The one thing you’ll observe here is that, well, this isn’t really handwriting. It’s just the illusion of pen and paper. If you can ignore that one factoid, then the essence of Lettrs is actually pretty sweet. Plus, there is an additional ‘Preserve a Letter’ feature that lets you upload and save handwritten personal letters, in what it calls – somewhat metaphorically – a ‘shoebox’.

Furthermore, you can display letters publicly via your virtual ‘fridge’, and explore thousands of personal and noteworthy letters – including historical writings from celebrities and public figures, and share them across the social sphere.

“The introduction of the Lettrs mobile app is another major step toward our goal of making letter-writing relevant and easily accessible for anyone anywhere, at any time,” said Lettrs co-founder and CEO Drew Bartkiewicz at the launch.

“In an age when most social media missives are quick hits without a great deal of thought behind them, I feel very strongly that people are hungry for more meaningful and deliberate communication in their lives. The Lettrs mobile app is all about making the process of letter writing much more convenient, purposeful and lasting.”

Handwriting is living on in various other technologies too.

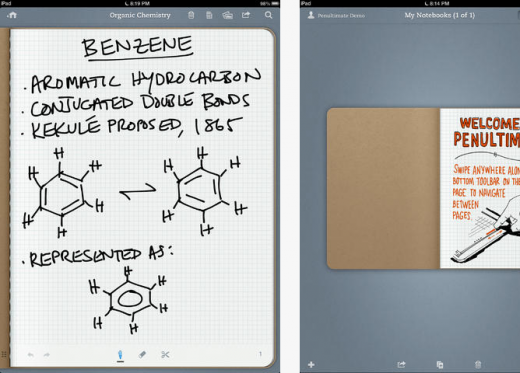

Penultimate

Back in April 2012, Evernote acquired Penultimate, a popular iPad app (it was the 4th most downloaded iPad app as of March 2012) that lets users write (or draw) directly on their tablet’s screen with a stylus, and save for posterity.

The so-called lifelike ink and paper makes you feel like you’re writing in a notebook, and syncs directly with your Evernote account.

Livescribe

Way back in October 2011, we brought you news on Livescribe’s Echo Smartpen, which we said dragged the humble pen into the 21st Century.

Echo’s main raison d’être is to transform your handiwork into digital form – this could be notes from a meeting, or sketches and doodles. It works with special paper, incorporating an array of tiny dots, as well as command icons at the foot of each page. The device comes with a notebook featuring this special paper, while the built-in mic lets you upload audio to correspond with the notes you’ve taken.

Then last year,

The pen digitizes everything you write and hear and automatically sends it to your Evernote account, from where you can play it back and associate your handwritten notes with the actual sounds you heard the second you took a specific note.

It would be more beneficial if your handwritten notes could be automatically converted into typed characters to be inserted into reports and so on, but some form of OCR integration is likely at some point in the future.

Evernote also launched its own Moleskine notebook last year, making it easier for users to transfer their penned notes to their online account. You can read our full review here.

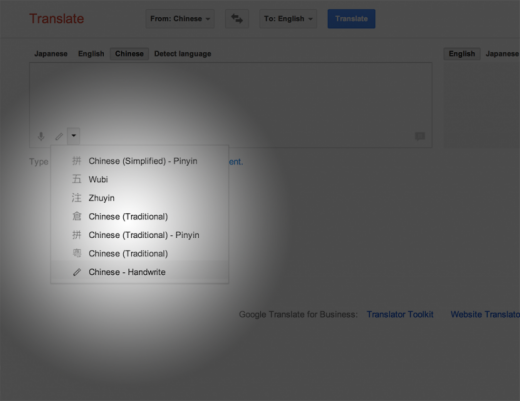

Way back in January 2012, Google introduced an interesting new feature to the Google Translate app for Android – handwriting support.

It started as an experiment with a couple of languages, though as of July 2013 it supports handwriting in 45 languages, on Android AND the Web.

If, for example, you want to translate the Chinese expression “饺子” to your native tongue, but have absolutely no idea how to type the characters, you can now write them out by hand. First, pick an input language (in this case Chinese) and if supported, you will see the input tools icon at the bottom of the text area which you can click to switch to handwriting mode.

Then all you have to do is draw out the characters on the main panel of the handwriting tool just like you see them, and Google Translate will take it from there.

At this juncture, it’s worth asking – does any of this really matter? Should we bother fighting the inevitable and accept that digital isn’t just the future, it’s the present and recent past too?

Perhaps, but nostalgia aside, if handwriting was to become obsolete, this could fundamentally change the way we learn and develop our literacy skills from childhood.

Handwriting on the brain

“Through a series of studies using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to probe how the brain processes stimuli in real time, we have demonstrated that, a) there is a distinct system in the human brain that is recruited during reading that is also recruited during writing, b) that the reading network develops as a function of handwriting experience, and c) that handwriting, and not keyboarding, leads to adult-like neural processing in the visual system of the preschool child.

These findings suggest that self-generated action, in the form of handwriting, is a crucial component in setting up brain systems for reading acquisition. There is support for the notion that handwriting instruction is positively connected to learning to read.”

Dr. Karin Harman-James, researcher at Indiana University, Department of Psychology and Brain Sciences, from ‘The Neural Correlates of Handwriting and its Effect on Reading Acquisition’

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that typing and handwriting require different skills. If you learned to ‘write’ entirely by keyboard and never saw a pen until adulthood, you would struggle to make much sense on paper.

Similarly, if you were lassoed to a pen or pencil until adulthood, you would be much slower to construct sentences with a keyboard. Surely these disparities have an impact on the development of our brains and, more specifically, literacy?

“New research evidence from brain-scan studies show that learning to write letters, including early manuscript lessons helps coordinate and activate linked regions of reading circuitry,” says J. Richard Gentry.

“Handwriting lessons should begin in kindergarten because these lessons are helpful to young children for learning to read,” he continues. “Brain development for hand-writers continues into late elementary. While more research is needed, it has been reported that even in adulthood there may be some advantages of handwriting over keyboarding. One informal study reported that about half of graduate students prefer to take notes by handwriting, versus notes on the computer.”

Angela Webb agrees, saying that handwriting isn’t just about pretty presentation, but is a functional tool for getting thoughts onto paper.

“If this is not able to be performed effortlessly, children (and adults) divert cognitive resources required for composing away into text production, compromising the written content,” she says.

“Researched benefits include the learning of letter-forms for reading, the generation and development of ideas when writing narrative and the assimilation and retention of mathematical concepts,” she continues. “Many adult authors say they handwrite early drafts to stimulate creative thought.”

Although handwriting may stimulate the creative juices, is there any direct link between handwriting ability and intelligence?

“Research shows no correlation between handwriting ability and general IQ,” says Webb. “However, the correlation between handwriting ability and academic achievement is very high. Children whose work is illegible are graded up to 25% lower than when well-handwritten; and children and adolescents who produce fewer words are rated lower for composition quality of content than those who write more.”

Gentry adds: “Handwriting is multi-modal, and engages touch, movement, and thinking making it more effective for learning than keyboarding alone.”

So…what does the future hold for handwriting?

We’ve taken a lot of information on board here, but are we any closer to establishing what the future holds for handwriting?

Based on our discussions with two individuals closely in-tune with education and literacy in both the US and UK, there’s nothing to suggest that handwriting is going the way of the dodo anytime soon. But the key here is to ensure it remains a core part of the school syllabus.

With smartphones, PCs and tablets proliferating society, there’s no doubt that handwriting will become less and less ‘essential’ in everyday life, but that doesn’t mean the age-old skill of being able to put pen to paper shouldn’t and won’t survive. And there’s clear evidence that this is broadly recognized.

“With more and more research, I’m optimistic that both handwriting and spelling will make a comeback,” says Gentry. “I think anyone who hasn’t been taught handwriting is disadvantaged. Although I embrace new technologies for literacy, new technology and handwriting shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. What happens when technology shuts down? Handwriting – and spelling – should always be a part of a good education.”

This is something Webb too agrees with, adding that while technology will undoubtedly increase across the spectrum, the unique properties of handwriting for “stimulating types of intellectual activity” will become more widely recognized as research improves.

“As handwriting is a taught skill, it is vital that it is not lost for future generations while we make these discoveries,” she says.

Image Credits

Image 1 – Thinkstock | Image 2 – Thinkstock | Image 3 – Thinkstock | Image 4 – Thinkstock | Image 5 – Thinkstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.