April 9th, 2012 will go down in shopping history as the day the software gods emptied the coffers to preserve mobile market share with two very disparate strategies. While both companies were acting in large part to block competitors, their moves couldn’t have been further apart when it comes to valuing ideas over users. Facebook paid $1 billion for Instagram, a photo app with zero intellectual property, while Microsoft paid $1 billion for a portfolio of 800 patents related to email and IM. Why are these valuations so high and what do patents have to do with it? The answer, as so many answers do, begins with Google.

goo·gle·pho·bi·a noun \ˈgü-gəlˈfōbēə\

pathological fear or loathing of Google

Protection Money

Googlephobia reached a fevered pitch last week as both Microsoft and Facebook took desperate actions to slow the ascent of the Android empire. Weeks earlier at SXSW, Facebook took notice as Instagram innocently announced its Android version. Hm, Facebook must’ve thought, an extra 30 million users might be somewhat appealing to a lonely social network like Google Plus. In reaction to this, Instagram casually doubled its valuation a week before the Android release.

Meanwhile, Microsoft is in a hardware war with the Android manufacturing universe and pundits agreed that AOL’s legal cache might have given Google some protection from Seattle’s best lawyers. Google didn’t bid in the open auction, but chairs around the world probably slept better anyways knowing that Ballmer’s purchase may have calmed some nerves. Still, are these protective powers worth $1 billion?

Same Price – Very Different IP

Both Facebook and Microsoft were looking to spend their billion to increase their mobile market share, but the difference in approaches to intellectual capital couldn’t be more stark. In order to look at the comparative value, we’ll need to look at some recent developments in the fascinating world of software IP that shed some, if dim, light on the magnitude of last Tuesday’s spending spree.

A Nano-Primer On Software Patents: Machine, Transformation, and Half-Toning

Machine or Transformation

How do you know if your software process, say, for filtering a picture, is patentable? According to the 19th century definition still on the books today, your clever idea requires either a specified machine, or it must change something physically. This terminology was famously used in 1972 to prevent software algorithms from being patented (legal eaglets see Gottschalk v Benston). It was further invoked by the supreme court in 2010 when they famously denied a patent for a process (Bilski vs Kappos), while at the same time admitting that maybe some software algorithms (that didn’t refer to a specific machine or to change the state of physical objects) deserved some sort of patent.

Half the Tone, All of the IP

The latest chapter in software patents happened in 2010 as the Federal Circuit weighed in against our shopper Microsoft and found that software processes, even those without unique machines or state changes, were patentable if they were specific and provided “functional and palpable applications in the field of computer technology”.

In that instance the beautifully named “Research Corporation Technologies, Inc.” was able to successfully defend its patent for half-toning — using dot gradients to mimic colors — from Microsoft. A victory for the protection of ideas and a patent for an algorithm! Confusion resolved? Hardly. Since 1972 through last week every software and hardware player with half a million to spare has been gathering up patent after patent to try to bluff each other into not suing for ubiquitous processes like half-toning or email or instant messaging. Half-toning seems especially resonant here, isn’t Instagram built around a process for manipulating images?

A menu from 1972’s SuperPaint, an Instagram Precursor

Facebook’s Purchase (No Sales, No Patents, No Problem)

Instagram has no real protectable intellectual property at all. It uses a hodgepodge of open source to deliver its services and its filters have been around since Superpaint. What Facebook gets instead of IP is users, 30 million of them. How much are users worth? For a company with a valuation of over $100 per user, Instagrammers are a bargain at $30 each. With a turf war out there, Instagram doesn’t need sales, as its investors realized from the get go, nor does it need any protected IP. Despite Zuckerberg’s claim that Facebook doesn’t “plan on many more of” these deals for users, the deal’s magnitude exposes a Facebook strategy: will pay for users, no patents necessary.

SuperPaint ran on the Nova800 (16 Bit!)

Microsoft’s Purchase (No Product, No Problem)

Conversely, Microsoft, a company once known for its software prowess, wants patent weaponry to continue its assault on Apple, Google and the smartphone manufacturers. In August, Google purchased Motorola Mobility for its 17,000 patents in a deal that likely pushed Microsoft into its bidding for AOL’s stash of IP. As the Wall Street Journal’s Gordon Crovitz put it, “The value of patents in software and hardware such as smartphones has everything to do with litigation risk. It has almost nothing to do with technology.”

Mobile Users – The Patent Alternative

What’s wonderful about these two surprising uses of $1 billion, is that they auger a world of mobile tech that is still a wide-open playing field. Once the meal-ticket of the startup, patents have become arrows stockpiled by the thousands by the mega-corporations of the Internet to protect shares of the mobile market. The top dollar paid for these patent troves shows that the mobile world is still anyone’s game. Meanwhile, Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram unveils a vision of the future where users, not patents or products, are the best way to protect and expand mobile marketshare. We’ve already seen startups following the lead of Instagram’s precursor “Burbn” by shedding their product-oriented approaches in favor of a clean, simple, viral quest for users.

The Winner

Facebook wins this billion dollar bargain hunt by acquiring 30 million users and announcing a new strategy in one surprising move. Instagram’s users might not ultimately bring revenues of $30 each, but with the high public valuation for Facebook, the immediate value of maintaining the top social destination for mobility is arguably priceless. Microsoft’s patent grab helps it accelerate its strategy of demanding rents from every mobile manufacturer but their bargain is less sweet as this legal battle can’t last forever. Either way, the new holy grail for startups looking to get noticed is clear: get mobile users.

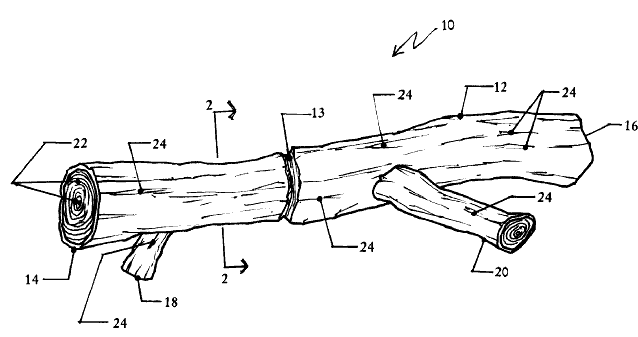

This article is dedicated to U.S. patent 6360693 which celebrated its ten year anniversary last week.

Dollar bills by Brian P Gielczyk via shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.