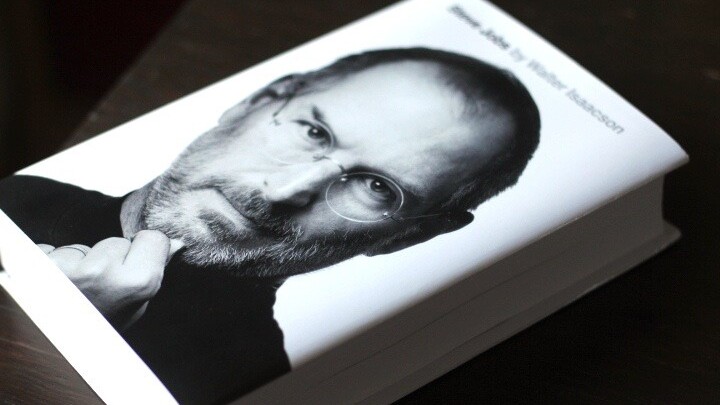

The story of Steve Jobs by the biographer of Henry Kissinger and Albert Einstein. If there ever was a no-lose scenario it was this one. How could this not be one of the best reads of the year, if not the decade?

It turns out that it is in fact a really, really good read, but perhaps not in the universal way that we had all hoped.

Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs unsurprisingly focuses a lot of attention on the companies and products that Jobs helped bring into being. As one of the most intuitive and inventive corporate personas of our time, his life is inextricably wound around those physical and corporate entities.

You cannot effectively tell the story of Steve Jobs without discussing the things that he made, they are–in many ways–one and the same.

But there are other facets to Jobs, some of which Isaacson manages to expose and hold up to the light, twisting and turning them to reveal both shining surfaces and buried flaws.

Others of which it seems will continue to be hidden to us as Isaacson was either unable to reveal them or, as he freely admits some will think in the introduction, he was brought under the spell of Jobs’ vaunted Reality Distortion Field.

One segment of readers who may be disappointed are those interested in a lot of the technical details. Isaacson is clearly not a technically minded person and many of his explanations of the hurdles overcome by Apple engineers or Jobs himself are sometimes simplified to the point of abstraction. This will make it frustrating for those that do understand these concepts and want a more granular approach to documenting them.

Another is those that are largely familiar with the history of Jobs and his companies up until the modern era. A significant portion of the bio is given over to the history of early Apple and the creation of the Macintosh. Both of these have been covered extremely well in Infinite Loop by Michael Malone and Revolution in the Valley by Andy Hertzfeld respectively.

But is there enough here to interest the rest of us who want a window into one of the most fascinating minds of the 20th century?

The contradictions of passion

Throughout the book, Isaacson paints a portrait of a man far more emotional and sensitive than his public reputation for being a brutal negotiator and criticizer of underlings would lead one to believe.

Notably, there are over two-dozen references to Jobs openly weeping over one subject or another. This has been noted by others reading the biography, but I think that there is a point here that is interesting.

Out of all of the times that it is mentioned that Jobs is feeling a strong enough emotion to cause tears, there are only one time that is it about person with which he had a private relationship—his ex-girlfriend and long-time love of his life Tina Redse.

Nearly every other time Jobs is mentioned as crying in the book, it is over anguish about a business venture or product.

He cries at the mention of Lee Clow, the masterful PR head that developed the Think Different campaign, among many others. He cries over arguments about the split of Apple partnership with Steve Wozniak. He cried when he told the Macintosh team he would be leaving Apple.

He even cried when he found out that the iMac would have to launch with a tray-loading CD drive instead of his preferred slot-loader.

Whether it is simply because they are the instances that Isaacson focused on or not, that stood out to me.

These tears, read in context, don’t necessarily indicate that he wasn’t emotional about people. In the contrary, he seemed to have much emotion on display, even when being what can only be characterized as ‘nasty’ to people who didn’t bend to his will or live up to his expectations.

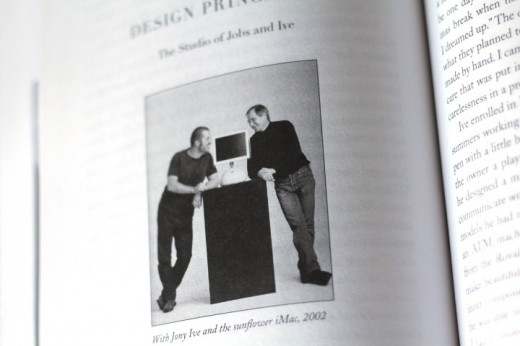

Jobs’ collaborator and self-described “spiritual partner” at Apple, Jonathan “Jony” Ive commented on the contradiction. “He’s a very, very sensitive guy. That’s one of the things that makes his antisocial behavior, his rudeness, so unconscionable,” said Ive. “I can understand why people who are thick-skinned and unfeeling can be rude, but not sensitive people.” (Isaacson, 461)

Yet Ive is shown to have a deep love for Jobs and carried on a great working partnership with him, despite this behavior.

Clearly Jobs was a man of passion who cared deeply about his life’s work and invested copious amounts of his emotional life into what he made.

This trait is one that can be seen in artists, musicians and writers and this pouring out of the self often leads to great achievements that last and impact lives.

Also mentioned throughout the book is the way that Jobs lived in a constant state of tension that existed between the fact that he made commercial products for people to consume and that he privately was a dedicated practicer of Zen Buddhism almost his entire life.

It may have been this tension between the rebel who revered counter-culture, and the established peddler of technology to the masses, that was the catalyst that allowed Apple to establish itself at the crossroads between technology and the humanities.

Jobs had a constant knowledge that clear thought—and clear design—could actually inspire people to create wonderful things. The commentator, comedian and one of the stars of the “I’m a Mac” commercials, John Hodgman put it succinctly following Jobs’ passing saying “Everything good I have done, I have done on a Mac.

There are many that feel that way and they may have the warring sides of Steve’s personality, the sensitive Zen student and the demanding, passionate and driven executive, to thank for it.

Second Act

While the biography doesn’t share the strict two-act structure that most ascribe to Jobs’ career–it delves into his time at Pixar with some interest as Jobs takes on the role of a proto-Disney that lacked Walt’s direct creative control but appeared to share many of his traits.

While sharing time between NeXT and Pixar, Jobs showed a newly minted ability to allow studio heads John Lasseter and Ed Catmull more control over the direct day-to-day operation and creative control over the movies produced, taking on the role of a facilitator and protector.

This is similar in many ways to the second phase of Disney’s career, after the studio got so large that he could no longer juggle all of its various projects, micro-managing all of the creative decisions as he used to do in epic story meetings where he would act out, with voices and movement, nearly all of a movie in production from beginning to end.

During Disney Studios’ growth to a larger campus, Walt took an obsessive interest in its design and construction, specifying everything down to the paint on the walls and the design of the awnings over the windows, which could be adjusted to allow more or less light for the animators.

I was struck by the similarity of Jobs’ obsession with creating Pixar’s new campus as a place that inspired creativity and fostered communication, sparing no expense in the materials (raw steel girders, clear-coated to show their natural beauty) and the way that it was enclosed all in one building around a central courtyard (rather than the traditional sprawling complex) so that the employees would have more interaction with one another.

Jobs would later employ this same design thought to Apple’s planned ‘spaceship’ headquarters, a large circular building around a central courtyard.

This design exemplified his belief in meeting face-to-face, ““There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email and iChat,” he said. “That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say ‘Wow,’ and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.” (Isaacson, 431)

As Jobs returns to Apple, Isaacson focuses largely on the high-level executive wrangling that went on in the process of ousting Gil Amelio as CEO. Many of these details are well known, but an interesting component is that Jobs had a certain reluctance, whether feigned or actual, to return as head of the company, even after Amelio’s forced exit.

This reluctance is interesting because it points to the fact that Jobs was recognizing that he would need to apply all of his considerable ability to resurrecting the company that had left him behind 12 years before. Was he having doubts about his ability to manage a company in distress? His experience with NeXT likely taught him a lot about managing a company from the ground up, but did its ultimate quasi-failure give him pause?

This is where things get a bit hazy. Isaacson describes several conversations that Jobs had with various friends, mentors and even supportive board members like Ed Woolard, asking them, perhaps in an attempt to convince himself, whether this was a good move or not.

But nothing in the book describes how Jobs made that important transition from a good negotiator and idea man capable of wormhole-like leaps in logic, to a steely supply-chain-minded CEO that was able to take Apple onward into a new era of design sensibility and profitability.

This lack is a sad one, as this is really the crux of Jobs career. This transition is one of the most remarkable about-faces in all of corporate history, and we still don’t know how or why it happened.

The one clue that we’re given comes in one of Isaacson’s ‘personal’ sections, in which he describes a session where Jobs plays the music on his iPod while sitting together on Jobs living room floor.

The music played shows that Steve retained his taste for Dylan, The Beatles and other classic artists, but it also shows us a man that was aware of the changes that time had wrought on him.

He played two ‘before-and-after’ song comparisons for Isaacson, one by Glen Gould from 1955 and then a second from 1981, just before he died. “The first is an exuberant, young, brilliant piece, played so fast it’s a revelation. The later one is so much more spare and stark. You sense a very deep soul who’s been through a lot in life. It’s deeper and wiser,” said Jobs. “Gould liked the later version much better,” he said. “I used to like the earlier, exuberant one. But now I can see where he was coming from.” (Isaacson, 413)

Perhaps the better example of this was Joni Mitchell’s ‘Both Sides Now’, which Jobs also played two versions of.

Both Sides Now (1969)

Both Sides Now (2000)

Both songs are identical lyrically, but the tone has changed completely. The later version is darker, more tapestried. It reflects the patina of years of life experience. It’s a stark transition between what is, on the one hand, a whymsical observation on the concept of world-weariness, and the lement of someone who has lived and learned it over the course of a lifetime.

Jobs’ reaction to listening to the second version was to say “It’s interesting how people age.” (Isaacson, 414)

Typically of Jobs, ever the intuitive thinker and showman, he does not explain the meaning, but a possible explanation can be found in this musical comparison session.

It seems that Jobs thought of his career much in the same two-phase way that many like to distill it. He saw in these songs the affects that aging and experience had on him, transforming him from the brash youthful iconoclast with a penchant for intuitive thinking, to someone capable of effectively managing a large company.

Yes, his management style was one of cajoling and intimidation, punctuated by a reverential deference to those he considered ‘pure artists’, but its undeniable that Apple was a far better managed company during his second tenure.

We will most likely never know exactly when the transition ocurred, although evidence points to his life-long devoption to Buddhism and Zen thought is the likely catalyst. What we can see though is that Jobs was aware of his transformation on some level and embraced it, allowing him to have a second period of intense productivity that made Apple what it is today.

A worthwhile read

While this may not be the definitive technical guide to how Apple managed to design and build our future, or the insider look at the mechanics of Jobs’ brain that some were hoping for, there is still value to be found.

The lessons that can be learned from Isaacson’s look at Jobs’ life may be more ones of inspiration than imitation, in the end.

No one would want to emulate the way that Jobs sometimes bullied and berated employees and friends, or denied aspects of his life like his illegitimate daughter.

But there is inspiration to be found in that Jobs managed to balance two distinctly different portions of his personality with one another, and create great things in the process. It shows that it is possible to have two warring parts of your personality that may seem mutually exclusive and allow them to work together to your purpose.

The desire for family and the drive to create, or the will to succeed and yet the emotion and passion of a creator. These things can coexist and perhaps even complement one other to create something new and different.

There are a lot of things that we still don’t know about Steve Jobs after Walter Isaacson’s book, but there are still things to be learned. The power of passion, the possibility of our very own ‘second act’. For those gems alone, its well worth a read.

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson is available on iBooks and Amazon.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.