Should cyborgs have rights?

It’s a question many find ridiculous. “Cyborg,” after all, conjures up a sci-fi humanoid-robot that exists in a far distant dystopia, long after global warming has smoldered our cities to the ground, our polar bears have burnt to a crisp, and Elon Musk’s grandson has emerged from his cryogenic chamber.

But cyborgs walk amongst us — and the vast majority of us are not far off from being considered cyborgs ourselves. After all, if our smartphones are glued to our hands, does that not make us a sort of proto-cyborg?

With new technologies steadily allowing for more sophisticated cybernetic augmentation, more and more individuals are electing for their bodies to be enhanced with machines.

As flesh and metal merge, this new form of person is cracking open a whole new realm of legal and moral complications on what exactly it means to be a human.

Why the fight for legal change now?

Cyborgs have actually been around for a while, with advanced prosthetics making up for various physical disabilities and limitations, and in doing so have steadily brought humans and machines closer together.

Machines can fill in where disaster and disability has left us behind, but many are now leapfrogging even further ahead. Transhumanists are setting their sights on how far we can physically stretch into the future — but the law is struggling to keep up, causing many to call for change. Earlier this year, bio-hacker Meow Ludo Disco Gamma Meow Meow (Meow Meow for short) was sued for implanting a travel chip card into his hand.

The Meow Meow incident is just one example of the ways in which cyborgs — especially those who have undergone voluntary enhancement surgery — have come into conflict with the law. Many question the fundamental ethics of enhancement technology, such as implants that extend life past natural terms, or make cybernetically enhanced individuals more qualified for certain sports or jobs.

Civil liberties activist and researcher Rich MacKinnon and cyborg activist and artist Neil Harbisson put forth the Cyborg Civil Rights at SXSW in 2016, as a reaction to the legal system’s slow response to recognize cyborgs. The five civil rights include:

- Freedom from disassembly

- Freedom of morphology

- Equality for mutants

- Right to bodily sovereignty

- Right to organic naturalization

These rights, according to MacKinnon and Harbisson, “exposed the redefinition and defence of cyborg civil liberties and the sanctity of cyborg bodies” and consequently “foresaw a battle for the ownership, licensing, and control of augmented, alternative, and synthetic anatomies; the communication, data and telemetry produced by them; and the very definition of what it means to be human.”

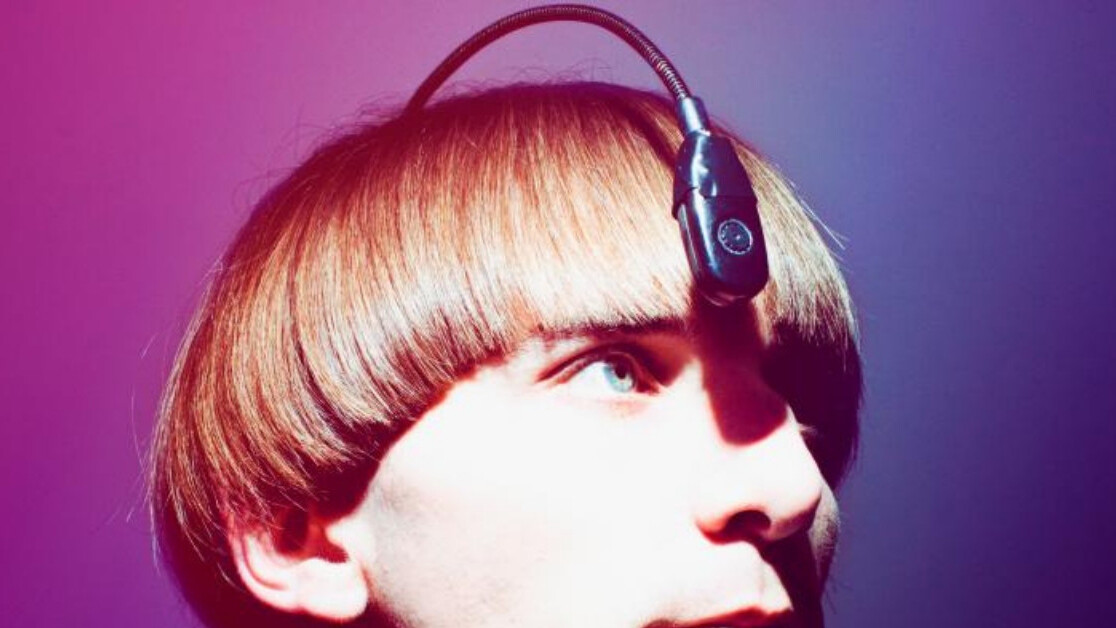

For cyborg activists, these rights are a matter of proving their body parts are not external machines, but a part of their very selves. That’s why Harbisson, whose cyborg ‘organ’ counteracts his achromatopsia, wrote the Cyborg Civil Rights along with MacKinnon. Harbisson was born with achromatopsia, a very rare kind of colorblindness which left him seeing the world in only shades of grey. The antenna-like sensor protruding from his head — or his “eyeborg” — allows him to “hear” color via different wavelengths which are translated into vibrations sent to his skull.

Harbisson became known as the world’s first cyborg after the British government allowed him to wear his antenna in his passport photo.

Along with most other cyborg activists and transhumanists, he views cyborgs as a natural progression of human evolution. He and his partner in crime, Moon Ribas, have run the Cyborg Foundation since 2010, a nonprofit organization which wants to “help humans become cyborgs, defend the rights of cyborgs and promote cyborg art.”

Art leads the way

Artists have long sat right at the cusp of radical change, using political unrest and transformation to inspire and inform their work. Art is therefore often an important part of political movements, and the fight for cyborg rights is no different.

Harbisson and Ribas are two of the most well-known cyborg activists using art to promote the cause. Moon is also cybernetically implanted, but in her feet. The Seismic Sense, as her implant is called, is an online seismic sensor which allows her to pick up the vibrations of earthquakes happening all over the planet in real time. She then performs these vibrations on stage, culminating into a display of dance and other movements.

The two have given talks and performances related to cyborg rights all over the world, actively campaign for legal change, and are also hosting a live Q&A session on our TNW Answers platform tomorrow.

Conclusion

As technology advances, robots are becoming more like humans and humans are becoming more robotic. The question of whether cyborgs should have distinctive rights remains hotly debated, but it is unquestionable that laws need to evolve to suit changes in society.

Technology is already disrupting the human body, and work from cyborg activists and artists like Neil Harbisson and Moon Ribas show how the very definition of humanity is changing.

You can ask Neil and Moon ANYTHING! Send in your questions now, and they’ll answer them tomorrow.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.