Too often we’re wasting the most creative people on the planet on the most trivial and ridiculous problems.

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks,” said data scientist Jeffrey Hammerbacher, founder of Cloudera.

What else are many of the top AI folks working on?

Weapons. Surveillance. Eliminating jobs.

Instead of solving world hunger or cleaning up the ocean or curing cancer, they’re working on killing people and getting people to buy crap they don’t really want or need.

That doesn’t just suck, that’s a massive humanitarian disaster.

Sure, the absolute best of the best in the field have the creative freedom to tackle whatever they want but those folks are few and far between. There are only so many pure research positions. The reason is simple. A company or college has to achieve incredible success before they have enough money to bet on long-term projects that may never work out.

Google is one of those companies. OpenAI is another. The University of Toronto kept the tiny field of neural networks alive for decades when it looked like it might never solve a real-world problem. There are others but not many.

The fact is to fund real, civilization-changing research you need surplus money. And surplus money doesn’t come easy.

The rest of the folks who aren’t lucky and skilled enough to compete for one of the few coveted positions that pay people to work on whatever they feel like have to settle for less noble work. People need to work to live and they go where the money is to feed their families. If the only companies that survive are making weapons and ads then that’s exactly what we’ll get from our best and brightest.

The problem cuts to the very heart of economics.

It all comes down to incentives.

Right now there’s no incentive to clean up the ocean. There’s no incentive to feed everyone. None of those things make money.

But what if we could change those incentives?

What if we could get the greatest researchers in AI to turn their brilliant minds to the most important problems facing the planet? We can.

To understand why you just have to understand a little about black box thinking, games, and the nature of centaurs.

Carrot and stick

AI gets a bad rap these days.

Whether it’s the machines taking all our jobs or superintelligent minds rising up and killing us all the story of AI in the pop press is fear.

Fear sells.

But the more I’ve thought about AI the more I realized the problem isn’t the machines:

It’s us.

As a Marine vet said in the amazing Ken Burns documentary on Vietnam, “Humans didn’t get to be the dominant species on the planet because we’re nice.”

As much as humans are capable of great wonders, unbelievable optimism and self-sacrifice, we’re also masters of death and destruction on a level that dwarfs even the most violent predators in the wild. Lions, tigers, and wolves got nothing on us. There’s but one source of evil in the world and it’s us.

Artificial Intelligence will be exactly what we make it be.

We’re the architects, the trainers, the fathers and mothers of our future creations. What we get out is what we put in. AI will be both good and evil because we are good and evil.

But how do we tip the scales to make sure it’s more good than evil?

First, we need to design machines that work with us, not against us. Instead of labor killers, we want labor enhancers. We want to extend and expand our capabilities.

That’s not as far fetches as it seems. That’s because machines and people are good at very different things.

Although the popular perception of AI is a universal intelligence, like a really smart Einstein that can kick our ass at everything, that’s really not the way intelligence works. Einstein understood the math of the universe but he couldn’t throw a baseball to save his life.

You may not think of hurling a ball as intelligence but you’d be wrong. It’s a highly specialized intelligence to throw a ball with pinpoint accuracy.

No algorithm works equally well for throwing people out at first base and solving General Relativity. If you’re good at everything, you’re by definition average at everything.

It’s called the no free lunch problem.

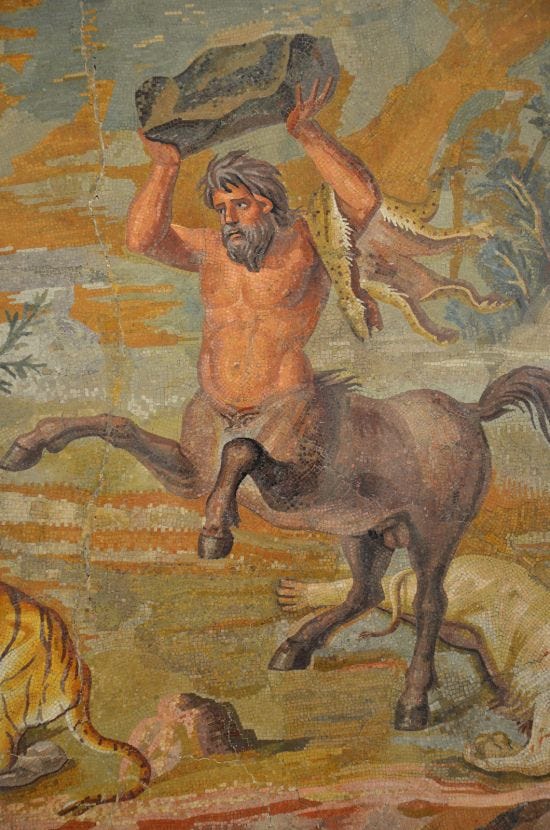

To be really good at something we specialize. That’s why a tiger’s intelligence is tuned for hunting and running and a dog is great at playing fetch with a ball. Author Nicky Case outlines this beautifully in his amazing article How to Become a Centaur:

An intelligence has to specialize. A squirrel intelligence specializes in being a squirrel. A human intelligence specializes in being a human. And if you’ve ever had the displeasure of trying to figure out how to keep squirrels out of your bird feeders, you know that even squirrels can outsmart humans on some dimensions of intelligence. This may be a hopeful sign: even humans will continue to outsmart computers on some dimensions.

Case goes further, giving us the fascinating tale of Gary Kasparov after he lost to Deep Blue. Everyone knows the first part of the story. IBM built a supercomputer that crushed one of the greatest grandmasters of all time in 1997.

But what happened next is even more fascinating. Gary started to imagine what would happen if AI and people worked together?

When it came to chess, Kasparov realized people are good at intuition and long-term strategy while computers dominate tactics and brute force calculations. So he decided to hold a new kind of tournament the very next year where humans worked together with machines.

He called it Centaur Chess, after the half human, half horse creatures of Greek mythology.

He invited “all kinds of contestants — supercomputers, human grandmasters, mixed teams of humans and AIs — to compete for a grand prize. Not surprisingly, a Human+AI Centaur beats the solo human. But — amazingly — a Human+AI Centaur also beats the solo computer.”

That’s right. The human/computer team beat the solo supercomputer too.

Two specialized machines, one biological and one silicon, beat the silicon only machine. Working together we can do so much more than we can by ourselves.

So that’s step one. Design machines that play to our strengths, that do the things we can’t do well. Build machines that work with us, not against us, labor enhancers, not labor killers.

Step two is trickier.

It goes back to those incentives. Reward and punishment. Push and pull.

Incentives shape our world and how we do everything. And right now our incentives are hopelessly broken.

We’re incentivized to get people to click ads or to spy on people. To change that we have to change the very structure of how we build businesses.

To change the world you have to change the input or you get the same output.

Outside the black box

Before we can change the world we need to understand just how vital those incentives are to shaping our reality.

With the right motivations, anything is possible. With the wrong motivations, we get a vicious cycle that destroys everything it touches.

The incredible book Black Box Thinking opens with a striking lesson in just how much the right or wrong motivations move the world. It tells the tale of two tragedies, one in the airline industry and one in health care.

One industry learned from their mistakes and the other keeps making the same mistakes again and again.

In 1973, United Airlines flight 173 took off from JFK airport in New York bound for Portland. Veteran pilot Malburn McBroom, a grizzled, fifty-two-year-old captain, was at the helm. He had twenty-five years flying experience, including in the dangerous skies of World War II Europe.

Everything was going smoothly until they got ready to land. McBroom pulled the lever to lower the landing gear. He’d done it a thousand times. Pull that lever and he could hear the doors buzz open and the familiar mechanical whine of the wheels coming down, finishing with a click as they locked in place.

But this time was different. A loud bang rocked the plane and it shook wildly.

Everyone looked around nervously. What just happened? Did the landing gear come down or drop into the ocean below?

McBroom radioed the control tower for more time and they sent back “turn left heading one zero zero.” They had him circling over the Portland suburbs.

More and more time passed. McBroom agonized over what to do next.

The crew made all the checks they could but they couldn’t be sure the landing gear had come down. They sent an engineer to see if he could see the bolts that shot up over the wing when the landing gear was down. They were but McBroom kept circling. He couldn’t be sure. The green light hadn’t come on. Why?

Time moved faster and faster. And suddenly a new problem hit. They were running out of fuel.

The engineer begged the pilot to land but he’d become obsessed. He kept circling and thinking, circling and thinking. Why didn’t the light come on?

A strange thing happens to the mind when we’re under stress.

Time dilates.

The pilot’s sense of time and space utterly “disintegrated.” No matter how much his crew pushed him, he kept circling.

And then they ran out of fuel.

They crashed screaming into the sprawling houses of the Portland suburbs, their voices echoing across the darkness.

But something beautiful came out of this horrible tragedy. It utterly changed the face of airline safety forever.

Before that crash, airlines had a horrible track record. Now they have one of the greatest safety records of any industry in the whole world. You’re more likely to die of a lightning strike than a plane crash.

They started teaching pilots what happens when you’re in crisis. They trained junior officers with assertiveness training, so they can blast through the hierarchy in times of trouble and get their voice heard.

They set up new rules. If people involved in a crash report everything perfectly accurately within two weeks of the crash, nothing can be used against them in a court of law.

The same is true for the investigative crew. When a crash happens a crack team of investigators arrive on the scene and go over everything inch by inch. Nothing can be used in a court of law. Instead, they share the data freely with all airlines and post a report on recommended safety changes. It’s open source problem solving before open source even existed. All airlines are required by law to implement those changes.

In sharp contrast to the brilliant response of the airline industry is the medical industry. Instead of incentives that push people to better and better safety, they gave us a system the ensures lying and secrecy.

A culture of lying liars

On March 29, 2005, Elaine Bromiley went in for a routine surgery.

It was a few days after Easter. Her husband, Martin, woke early at 6:15 AM and got their two children, Victoria and Adam, out of bed and ready for the day.

“It was a rainy spring morning” and the “kids were in high spirits.”

Elaine was a spunky thirty-seven-year-old woman who’d worked in the travel industry. She suffered from an aggravating sinus problem for years and she finally decided to get it taken care of once and for all.

Her doctor had thirty years of experience and was well regarded.

“Don’t worry,” her doctor told her. “It’s a routine procedure with little risk.”

By 7:15 Martin packed the kids into the car and they headed for the hospital together. The doctor set a light, relaxed tone, asking the family a few easy questions as Elaine got into her blue hospital gown and joked “How do I look?” to her daughter.

By 8:30 the head nurse, Jane, arrived and wheeled Elaine away for her procedure. “Byeee,” she chirped as Jane rolled her to the operating room, her son waving.

Her husband took the kids grocery shopping, picking up all the things they needed for a fine welcome home meal.

Back in the prep room, her anesthetist, Dr. Anderton, a veteran with sixteen years experience, pierced her vein and started the drip to set her off to a gentle sleep. But “anesthetics are powerful drugs. They don’t just send a patient to sleep; they also disable many of the body’s vital functions, which have to be managed artificially.”

When you go deep under you need help breathing. Doctors use a laryngeal mask that snakes down the throat and helps your lungs do their vital work.

Anesthetics hit everyone a little differently. But some people they hit badly.

And Elaine was one of them.

When Dr. Anderton went to put on her mask he couldn’t get the breathing tube down her throat. Her jaw muscles tightened up. Usually, a stronger dose will loosen the muscles but this time it didn’t work.

He tried smaller masks but they didn’t work either.

Two minutes later, Elaine was crashing hard, her face turning bright blue.

The doctor moved to plan B, a “tracheal intubation.” He delivered a powerful paralyzing agent to her jaws so he could pry them open and get the tube down her throat.

The drugs worked but that’s when he ran into another problem. He couldn’t see her throat. It was covered by the soft palate, a rare genetic quirk. And no matter how hard he tried the tube wouldn’t go down.

The situation went critical fast.

The head nurse knew the next move. Jane came in with the tracheotomy kit. It was a risky last resort. They could bypass her mouth altogether and go right through her throat.

But the doctors didn’t pay any attention to her.

They were lost, time dilating badly. Jane stood there dumbfounded, as the doctors tried to jam the tube down her throat again and again. She wanted to call out to them but she was scared.

“Maybe it’s my fault if it goes wrong?”

She didn’t want to be liable.

Also, the doctors were the authority figures. She was just a junior employee.

“Maybe they already decided against the tracheotomy for some reason?”

So she stayed quiet.

By 8:55 it was too late. Elaine dropped into a deep coma, her brain starved of oxygen for twenty minutes. She was transferred to intensive care.

Thirteen days later she was dead.

The contrast between this situation and the response of the airline industry is stunning.

Doctors reported vague reasons for her death like “unforeseen circumstances,” calling it a “one-off.”

In the medical industry, reports like that are common because doctors can easily get sued for anything that goes wrong. Insurance punishes them and the hospital. The board cracks down.

Nurses like Jane know their place: the bottom. They exist in a rigid hierarchy. If they break rank they get fired and may never work again.

Nobody learns from what happens. So it happens again and again.

Instead of being incentivized to tell the truth, doctors are incentivized to cover their tracks and lie.

That is the power of incentives. With the right incentives, people grow and change. They can solve any problem, become smarter, stronger, faster. With the wrong incentives, the same horrible and avoidable mistakes happen over and over.

The definition of insanity is doing the same things and expecting different results. We live in an insane world that so often incentivizes the wrong things.

Change that and we change everything. But how do we change it?

The games we play

We already have a template: games.

To understand why let’s take a look at a few people already running games for AI researchers.

Kaggle hosts contests to bring together the best data scientists in the world to solve real problems for cash prizes.

It managed to make a real difference on some big and challenging issues, like detecting lung cancer. The Data Science Bowl of 2017 offered one million dollars to anyone who could design a system that spotted tumors on high-resolution scans. Before the contest, the false positive detection rate was almost 90%. That meant a lot of people didn’t get the right treatment or got treated too late which means a lot of folks died unnecessarily.

The winners dramatically improved the rate of detection even with very little data.

It’s proof positive that games can change life for the better.

And it’s also proof positive that the best data scientists want to solve real problems instead of getting people to click more ads. Second place finisher Daniel Hammack wrote this about the contest:

We were also encouraged by the hope that our solution to this problem will be more widely useful than just winning some money in a competition — hopefully, it can be used to help people!

But there are only so many million dollar prizes to solve cancer. This year’s contest is another one to help beat disease but the prize is $50,000. Nothing to sneeze at but not a million dollars.

The fact is people are motivated by both money and altruism but the money often dictates whether someone is spending their late night and evening hours on a project or making that project priority one during the workday.

To start a contest on Kaggle you need to be one of those companies that have surplus money laying around or already has a big contract in place. Science Bowl 2017 was sponsored by Booze Allen Hamilton. And you can bet they had a $100 million dollar contract with some medical diagnostics company if they were offering such a big prize.

As we’ve already seen that kind of money is rare.

Of course, Kaggle isn’t the only game in town. The algorithm marketplace Algorithmia just sponsored a Kaggle-like contest with a twist. They designed an automated smart contract using Ethereum that can test and verify results and deliver the prize without any human intervention. It’s an innovative attempt to create a programmable ecosystem to solve big problems.

As Venture Beat puts it:

This competition is really a proof-of-concept test of a system that could allow anyone to create their own smart contract and solicit a custom machine learning model to solve a particular problem. That could help organizations that want to apply machine learning to a particular problem but don’t have the resources to hire a data scientist. Algorithmia’s method doesn’t require participants to trust one another (since all of the components are controlled by the contract), and it automates reward payment.

Of course, Algorithmia has the same problem Kaggle already has now. You need someone with the money to offer a reward. And the people with the money are not offering rewards to clean up the ocean. It goes back to those pesky incentives again. People have incentives to build a bigger business and grow their wealth but not to save the planet.

But the key to finally fixing our broken economics is only a blockchain away.

It starts with a little-known company called Numerai, that raised millions via ICO last year to create in AI hedge fund. Numerai uses ongoing AI contests that pay winners with their custom cryptocurrency. The data for the contest is partially encrypted so the data scientist doesn’t completely know what problem they’re solving but it doesn’t take a genius to figure out that they’re creating ways for the hedge fund to trade more effectively. Every few weeks a new problem spawns and data scientists swarm to solve it and win money via smart contract.

It’s an ingenious idea on a number of levels but it’s also totally wasted on the trivial. Instead of using that brilliant concept to solve real problems we’re using it to make more money.

Now don’t get me wrong, making money is great and I don’t begrudge Numerai their chosen path. I’m a cryptocurrency trader and I love to make money.

But if that’s all that we’re going to do with the explosive potential of crypto and AI than we should stop right now because we’ll just end up with more of the same world we already have right now.

We need to reach higher. We can reach higher.

And as it so often is, the answer is right in front of us.

What if we merged the ideas of Numerai and the ideas from my article “Why Everyone Missed the Most Mind-Blowing Feature of Cryptocurrency“?

Remember that I said the feature everyone missed was distributing money at the point of creation. Early cryptos like Bitcoin figured out how to print money without a central authority but they used the exact same distribution model we’ve always had, top down.

Just like fiat money Bitcoin is delivered right into the hands of a tiny few. Instead of unelected central banks, we have unelected miners who are only slightly less centralized.

But change the way you distribute money and you change everything.

The problem with Kaggle and Algorithmia is they have to go buy or borrow the money. Someone already has that money and they need to get some of it. But it’s no surprise that the people who got it aren’t giving it away.

Numerai figured out they could print their own money and deliver it via contests at the point of creation.

The key is to expand the nature of the contests.

Let’s build a cryptocurrency platform and DAO dedicated to solving the biggest problems in the world today. Think of it as a public trust, a charity, and Kickstarter on steroids.

The problems would be submitted by a council of dedicated scientists, futurists, and thinkers or voted on by the public. We could have fast track problems submitted by the council and publicly submitted challenges and a robust voting system that filters spam and joke requests. Its very purpose would be to distribute money as it’s printed to the people who create value for all of us.

Not only would the mining and minting system deliver the money but people could donate to the system to grow its power to change the world.

And because the system is creating its own money for its own goals it doesn’t have to bow to the incentives of the people who already have the money now.

That will break the back of the old incentive system and create a new one that’s aligned to the greater good not just to lining the pockets of whoever build the system in the first place.

The old system was good for getting us where we are today. Don’t hate it. It was a step in our evolution and a necessary one to get us from tribal warfare to modern industrialized society. But now we’re ready for a new system, one that can solve problems the old system never could.

It’s already within our grasp. If only we have the courage to reach out and grab it.

This story was originally published on Hacker Noon: how hackers start their afternoons. Like them on Facebook here and follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.