The bombing campaigns of World War Two left an indelible mark on the world’s towns and cities and in the memories of the people who survived them. In a new study, we found that the most destructive war in history also made its mark in our atmosphere.

In an age when long-term monitoring of the environment is increasingly important, scientists are turning to historical datasets for clues in solving present-day science puzzles.

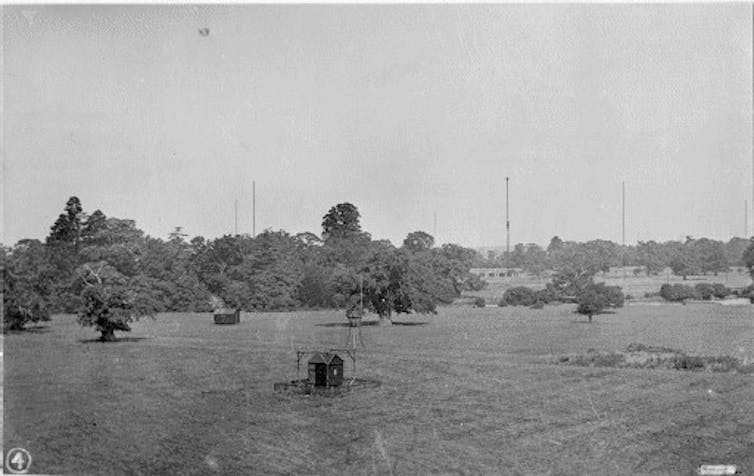

One such dataset is the unique record of the Earth’s ionosphere – the electrified region of the Earth’s upper atmosphere, which was painstakingly recorded from 1933 onwards at the Radio Research Station near Slough.

Scientists at the RRS were monitoring the ionosphere as it was then vital for long-distance radio communications. Shortwave radio is reflected by the ionosphere and allows the signal to be transmitted long distances over the horizon.

They had noted that the density of the ionosphere was extremely variable and had set up the monitoring station in order to look for patterns in this variability. Much of this is due to changes in solar activity.

The ionosphere is created when x-rays and extreme ultraviolet light from the sun are absorbed by our atmosphere, electrifying it. We now know, thanks to a fleet of spacecraft monitoring the sun, that not all of this variability can be explained by solar activity. Attention is increasingly turning to sources from the lower atmosphere and the ground.

But where to find ground events capable of leaving a signature at the edge of space? The answer lies in the past. World War Two witnessed an explosive arms race, which culminated, in its most extreme form, in the atomic bomb.

But most destructive energy still came from conventional weapons. Allied aircraft dropped over 2.75m tons of TNT, the equivalent of 185 Hiroshimas.

The RAF’s four-engined Lancaster bomber with its 11-ton payload could deliver more explosive energy than any other aircraft in World War II. The American Liberator could carry six tons, the Luftwaffe’s Heinkel 111 four.

Individual British bombs also grew more deadly. In 1944, two six-ton “Tallboys” capsized the German Tirpitz battleship, and the 11-ton “Grand Slam” could start landslides. Such seismic events were, of course, few and far between. Most of Bomber Command’s effort was targeted not at specific installations, but whole cities.

Here, too, the scale of ordnance was devastating. The RAF and US Air Force dropped 42,500 tons of high explosive on Berlin alone, plus 26,000 tons of incendiary bombs.

So-called “blockbuster” bombs – two, four or even six-ton barrels of boosted TNT – fused to explode a few hundred feet up, would blow off roof tiles and shatter windows within 500 meters.

Direct hits pulverized whole apartment blocks. Aircraft flying a mile above the blasts could have parts blown off and the pressure wave could even collapse the lungs of those caught within it.

Subsequent incendiaries would then penetrate structures, designed to set off a firestorm. This only fully succeeded twice – in Hamburg in August 1943 and Dresden in February 1945 – when tens of thousands perished.

The strategic bombing war documents numerous other area bombing raids, each of which involved hundreds of aircraft and up to 2,000 tons of high explosive.

How the Blitz helped modern science

The German authorities’ punctilious recording of the times and payloads of raids, coupled with RAF Bomber Command mission logs, made it possible to construct a database of possible ground events which might have produced shockwaves capable of being detected in the ionosphere.

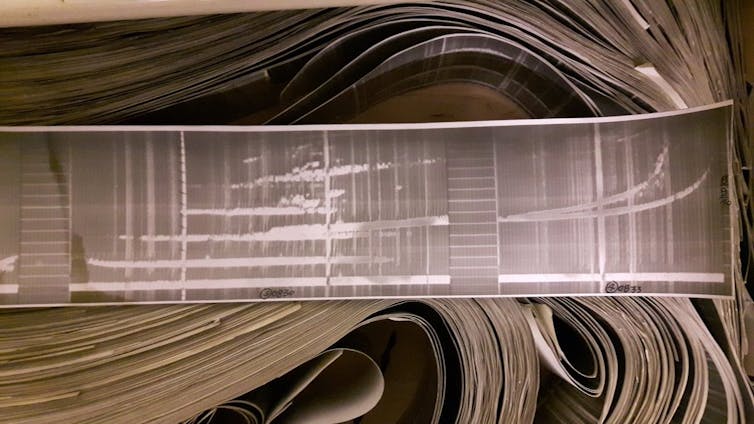

Ionospheric records from the Radio Research Station are now archived by the UK Solar System Data Centre at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, UK. The record shown below is for 08:30 on September 8, 1940, the morning after the start of the London Blitz when 700 tons were dropped by the Luftwaffe.

By combining data from 152 major bombing raids, it was possible to determine that the ionosphere was weakened, albeit only slightly, by these events.

While the exact details will require careful modeling, one suggestion is that, as the shockwaves travelled upwards through an ever-thinning atmosphere, the amplitude of these waves grew until they broke and, like waves crashing against a beach, deposited their energy high in the atmosphere as heat.

This change in temperature would have altered the chemical equilibrium in the upper atmosphere for a few hours, enhancing the loss of ionization and weakening the ionosphere. While these events will have had no lasting effect in the ionosphere, a typical “blockbuster” bomb was equivalent to the energy in a lightning strike.

So, armed with an understanding of how much energy is required to perturb the ionosphere, we can now turn our attention to modern ionospheric data and the influence of natural phenomena such as thunderstorms, volcanoes and earthquakes.

This serendipitous connection between data sets from two apparently separate disciplines suggests that answers can be found in the least expected places.

This article is republished from The Conversation by Patrick Major, Professor of Modern History, University of Reading and Chris Scott, Professor of Space and Atmospheric Physics, University of Reading under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.