Over the past 10 years or so, electric vehicle battery technology has evolved to the point where cars can be charged from zero to 80% in a matter of minutes. But a group of scientists in the US believe they have made a breakthrough that could lead to even faster-charging batteries.

In highly simplistic terms, the researchers witnessed how electrically charged particles move around inside a battery.

[Read: Scientists invent a faster and cheaper way to repurpose EV batteries]

The scientists, led by the US Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, observed in real-time, how lithium ions move through lithium titanate (LTO), an alternative fast-charging battery electrode material.

The important part to acknowledge, is that these particles move around when the battery is discharging. If those particles can be enabled to move around faster, scientists could develop faster charging and discharging batteries.

“Consider that it only takes a few minutes to fill up the gas tank of a car but a few hours to charge the battery of an electric vehicle,” said Feng Wang, co-author and materials scientist at Brookhaven Lab’s Interdisciplinary Sciences Department.

“Figuring out how to make lithium ions move faster in electrode materials is a big deal, as it may help us build better batteries with greatly reduced charging time,” they added.

But how?

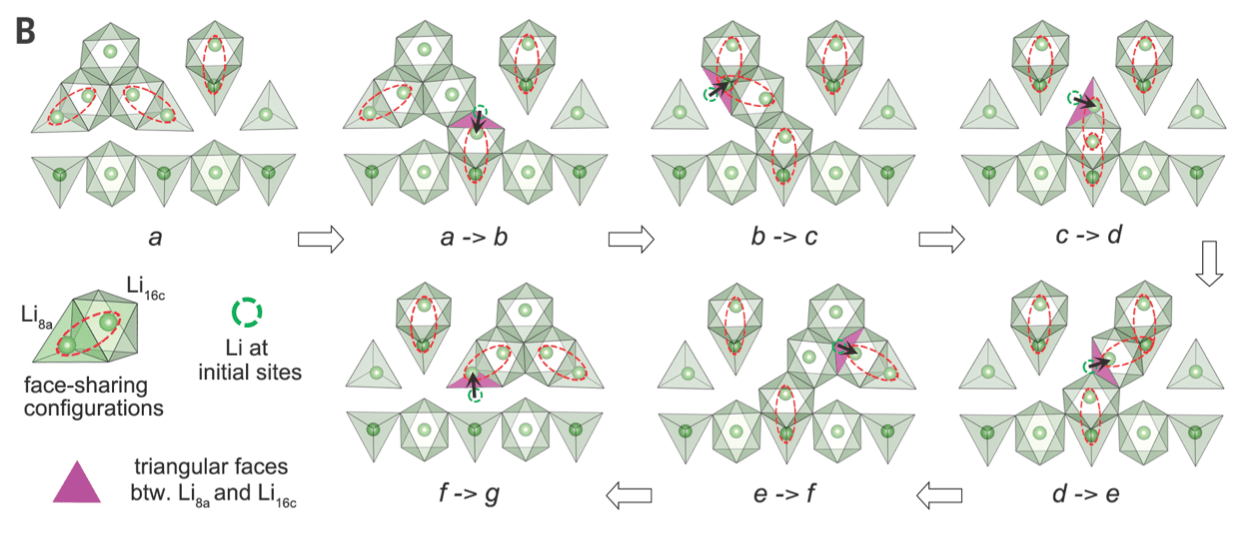

Scientists used a specialist electrochemical cell (think battery cell) inside a transmission electron microscope (TEM) to “track the migration of lithium ions in LTO nanoparticles in real time.” It allowed researchers to actively watch, on a microscopic level, what is happening inside a battery as it charges and discharges.

They found that LTO takes on new atomic forms between its starting and end state; the scientists refer to these forms as “local polyhedral distortions.” They say the distortions lower energy barriers and provide what is effectively a highly conductive, atomic highway through which lithium ions can travel. It lets the ions travel around faster than in conventional batteries.

According to the researchers, this makes LTO a desirable alternative to the graphite electrodes commonly found inside lithium-ion batteries. What’s more, LTO resists lithium plating on the surface of the electrode, a common downside of lithium-ion batteries which contain graphite.

Back in 2014, another group of scientists from Technical University of Munich found that excessive lithium plating can form during charging of certain batteries. If this occurs, it can shorten the lifespan of the battery and even lead to potentially dangerous short-circuits.

Despite the complexity the research, the potential contribution should be fairly evident. This discovery could lead to faster charging batteries that aren’t subject to degradation in the same way as conventional lithium-ion graphite cells. But there’s still a long way to go.

So, what next?

The scientists say they will move on to explore how using LTO in batteries affects heat generation and capacity loss with high-rate charge cycling. Researchers remain hopeful they can address these issues, though. But it’s the outcome of this next phase of studies that will really cast a light on how useful LTO might be in real world applications, like electric vehicle batteries.

Earlier this year, scientists from the UK invented a faster and cheaper way to repurpose end-of-life electric vehicle batteries. By reusing EV batteries, they can be put to good use as off-grid energy storage, rather than becoming useless waste.

It’ll likely be years before we have high-capacity EV batteries that charge completely in just minutes, with no detrimental side effects. But the technology is heading in the right direction.

If you want to read the full paper you can find it in the last edition of Science.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.