For several years, third-party cookies have been the mainstay of online audience tracking, but now they are finally on their way out. This is hardly a shocking development for anyone who has been observing trends in the media industry, marketing technology and privacy sensitivities in recent years.

And yet, amid the whirlwinds of the industry’s response, it’s become abundantly clear that the demise of the cookie is probably a good thing for everyone involved – audience members, publishers and even marketers.

The cookie’s place in history

By way of a quick review, cookies are those small bits of code dropped onto your browser to record your user activity. They’ve been in use since the 1990s, practically the dawn of the internet, in two forms: first-party cookies, and third-party cookies.

First-party cookies are those dropped by the sites you visit in order to track whether or not you’re still logged in. These cookies aren’t going to disappear any time soon.

Third-party cookies, however, record your browsing history, user ID, session ID, and more. They’re commonly used by marketers who want to know what you’re interested in so they can target you with relevant ads, but cookie owners could potentially sell your data to anyone.

These are the cookies that annoy internet users and privacy advocates, and they are the ones whose death so many industry professionals are talking about right now.

The cookie’s sudden death has been a long time coming

The cookie’s demise has been written on the wall for some time. Back in 2013, Paul Cimino, a VP at Merkle, gave it just five more years of life, saying that cookies are flawed and invasive, and were never intended for these purposes.

Many trends have been gradually diminishing the efficacy of the cookie. They’re only any use if the majority of internet users enable them, but the number of people turning off third-party cookies has been steadily rising and more browser apps are switching them off by default.

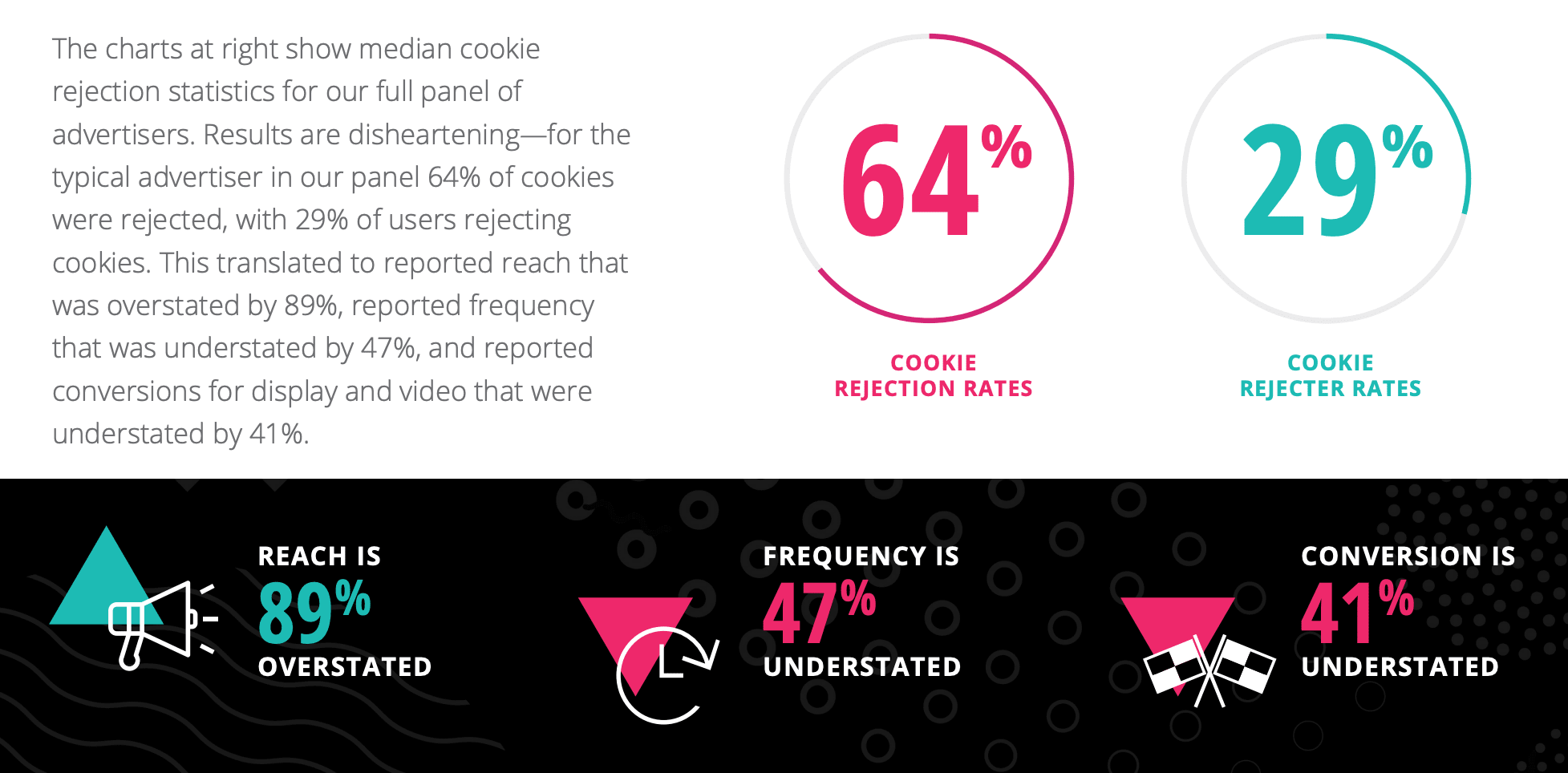

People generally dislike the feeling of someone tracking their every online move. In 2018, a report from Flashtalking discovered that 64% of cookies are rejected, either manually or with an ad blocker.

As a result, today, Safari uses Apple’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) to block cookies; Firefox applies Enhanced Tracking Protection (ETP); Microsoft Internet 10 has a Do Not Track setting by default. Since Chrome is responsible for 62.5% of cross-device internet usage, Google’s decision to join the cookie-blocker club with its new version is only the final nail in the coffin. The company also announced in January that by 2022, Chrome will stop supporting third-party cookies altogether.

Recent privacy legislation like GDPR and CCPA include rules governing when and how cookies can be used, and contain complicated requirements regarding how to store and use the information they record. In 2019, the CJEU, Europe’s highest court, ruled that websites must acquire the user’s active consent to cookies, without presenting any pre-ticked boxes.

Additionally, as awareness of children’s online safety grows, the FTC has been issuing tighter rules about cookies on websites used by children, forcing cookie owners to carefully consider whether a child would be likely to visit their site.

In parallel to these developments came the rising use of non-cookie-friendly devices for browsing the internet, such as tablets, smartphones and Kindles, cutting cookie-dependent advertisers off from programmatic ads. The booming mobile ad market provides a useful case in point for those opposed to third-party cookies, proving that it’s possible to run ads without them.

Behavioral advertising should crumble with the cookie

Opposition to behavioral advertising in general, which is primarily enabled by third-party cookies, has been building for a while. The backlash is grounded in sentiments far more alarming than that creepy feeling you get when stalked around the internet by retargeting ads.

Behavioral advertising has massively increased the power of big tech companies like Google and Facebook. Through behavioral targeting, these behemoths have created a movement of “surveillance capitalism” that monetizes your data for ads. It bears much responsibility for the echo chambers that sway elections and radicalize Islamic terrorists and white supremacists by continually feeding them more radical content that matches their current interests.

Behavioral targeting has terrible power to remind us of past traumas and can trigger anxiety or depression by serving up ads that hit a sensitive nerve. It can even place people in danger if, for example, a teen who is uncertain about their sexuality is “outed” prematurely to their unaccepting family by behavioral ads that respond to their exploration of the topic online.

This is why rising numbers of people are pushing to ban behavioral advertising entirely in order to dismantle a system that incentivizes companies to gather intimate data about our daily lives and sell it to third parties in the form of targeted ads. Many believe that a better alternative is contextual targeting, which determines which ads to display based on the topic of the web page being loaded.

It makes sense, after all, to assume that someone reading an article about cat grooming might be interested in an ad for cat food, for example. Contextual ads match the expectations of the audience, don’t invade anyone’s privacy, and protect brands from the embarrassment many have faced recently of having their ads appear alongside extremist or adult content.

In 2018, the New York Times stopped its behavioral advertising entirely in Europe in response to the introduction of GDPR, and replaced it with contextual and geolocation-based ads. To the surprise of many skeptics, its advertising revenue remained steady.

Marketers don’t need to panic

Marketers’ first instinct might be to panic, but third-party cookies aren’t that big a loss. The truth is, for the most part, programmatic retargeting and personalized ads that relied on cookie data have failed to live up to their own hype. On average, ad reach was overstated by 89%, frequency was understated by 47%, and conversion for display and video by 41% according to the aforementioned Flashtalking report.

Cookie-fueled behavioral advertising forced brands to dance around the requirements of privacy regulations, hoping not to cross the line and get fined for breach of GDPR, CCPA or other privacy laws. Why not replace that tension with a better model? It’s time to turn to newer, better tools.

With no real workaround for the failing third-party cookie, marketers, publishers, and brands need to build a new audience analytics ecosystem. Contextual ads are returning to the spotlight, requiring marketers to innovate new ways to target and track them.

But the only way to make this new ecosystem work will be to build a solid foundation of meaningful first-party data, and that in turn requires marketers and brands to work together to build a community that meaningfully engages with audience members and harnesses their support and willing cooperation.

Gaining a rich view of the customer depends strongly on user feedback, reviews, surveys, and other information provided voluntarily. Consent popups aren’t enough.

Marketing will be forced to rediscover authenticity in brand voice and messaging, since this level of user collaboration relies on rebuilding damaged consumer trust. The challenge at hand, then, is to give people a reason to create a login account with you.

Brands will still need to link together all their consumer touchpoints, including data flowing from first-party cookies that track visitor behavior on brand-owned sites and assets, and IoT data that tracks consumer preferences and behavior.

Data management firms are working on creative ways to leverage first-party cookie data into anonymized segments that can guide marketers without compromising user privacy.

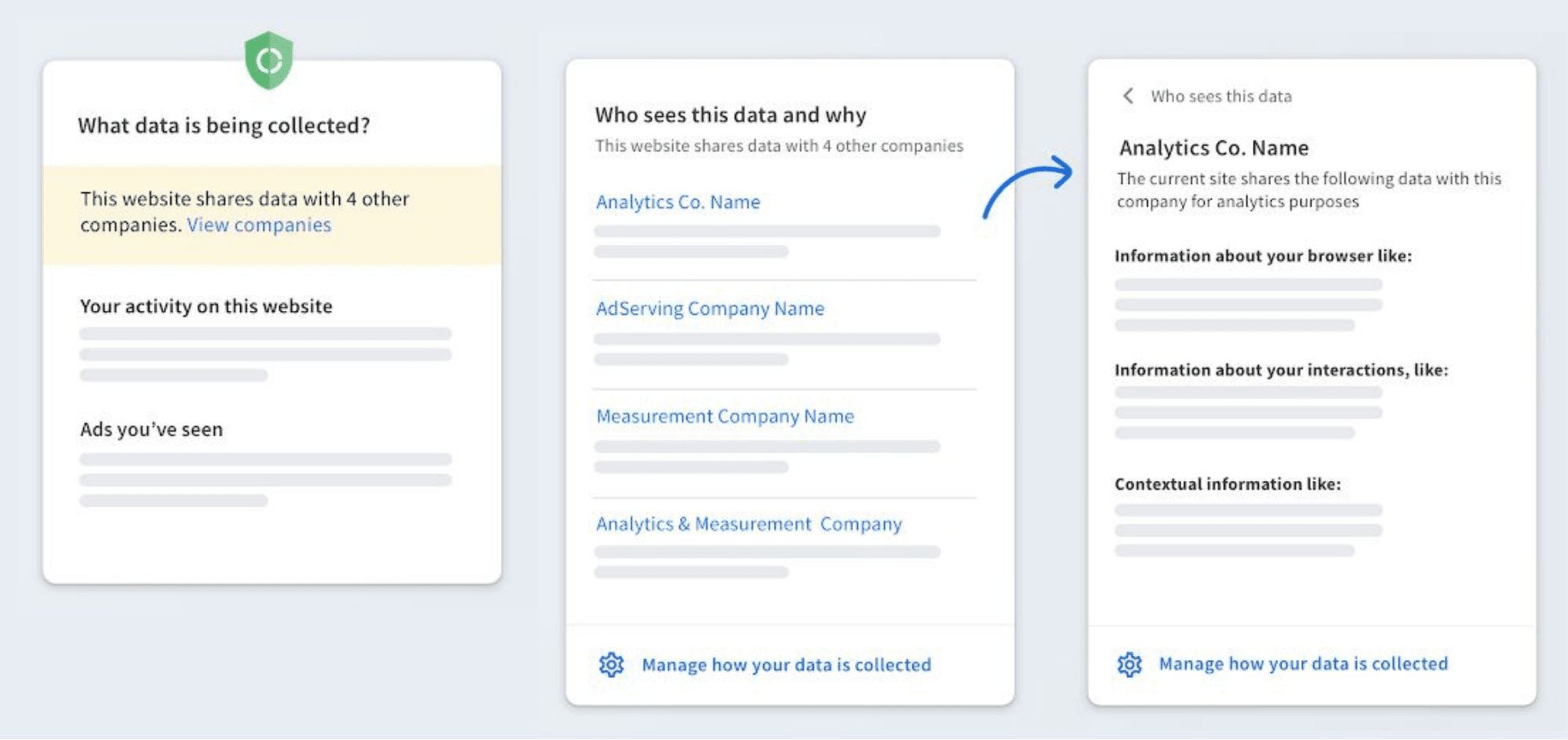

Google suggests advertisers use its new Privacy Sandbox, a family of APIs which will allow publishers to agglomerate audience data and anonymize it for marketing use as cookie workarounds. Below is a mockup that Google released last May, sharing some new concepts around privacy control initiatives in the months prior to announcing the Sandbox initiative.

Other walled gardens of data are springing up rapidly. Facebook and Amazon each already own significant amounts. Groups of publishers and advertisers are also banding together to consider creating a cross-platform login identity system, allowing partner organizations to share first-party data spanning media properties. Within walled gardens, ad targeting can be people-based and highly accurate.

Advertisers may also need to switch to smaller campaigns, in order to resolve the problem of attribution in a cookie-less world. Attribution may rest once again on last-click, forcing ad agencies and marketers to come up with new ways to measure the effects of variants to their creative.

For publishers, the fall of the cookie is a cause for celebration

Publishers are delighted about the cookie’s demise. The claim that publishers benefit from targeted ads, because they sell for more than non-targeted or contextual ads, was recently revealed to be nothing but a myth. It turns out that targeted ads can raise revenue by only around 4%, or $0.00008 per ad. The results of the New York Times experiment in Europe added fuel to the fire. Finally, publishers are waking up to the way that behavioral targeting risks cheapening the tone of their publication.

Large publishers gather their own first-party data about audiences, which they can leverage for ad placement and measurement. However, until now, third-party cookie owners got in the way of the relationship between publishers and advertisers, preventing publishers from charging advertisers directly based on their own data.

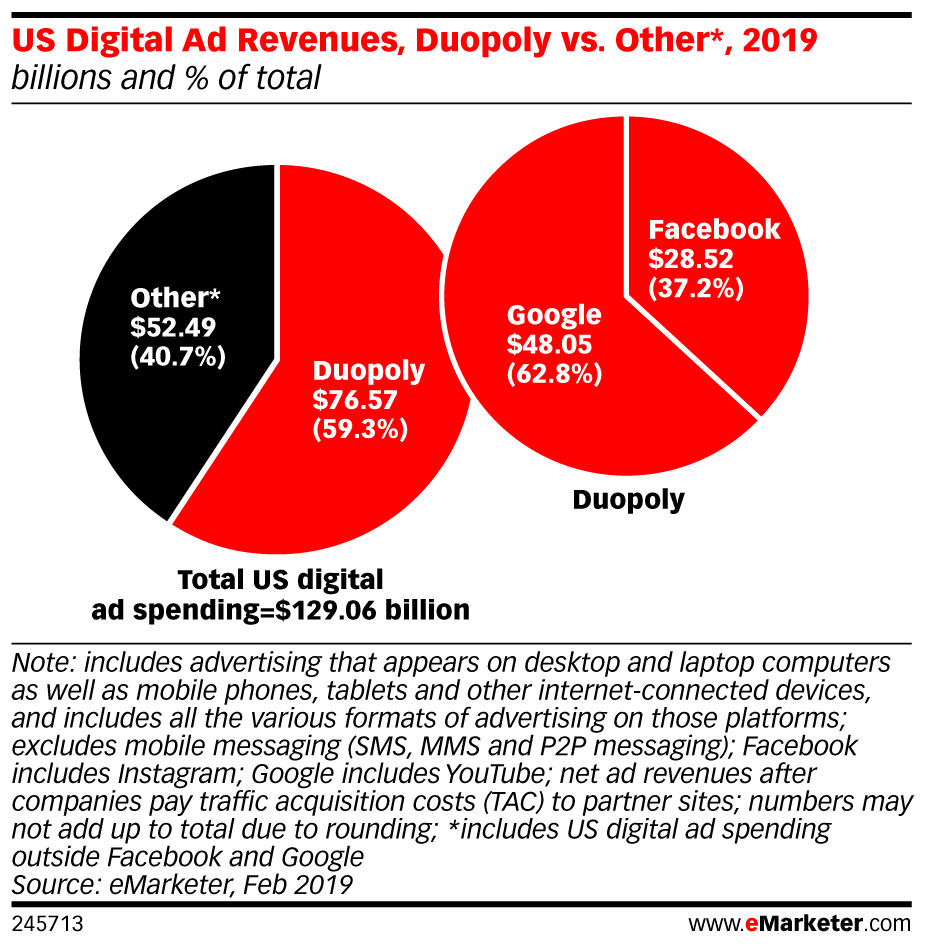

Instead of flowing to publishers, over 59% of digital ad revenue goes to the duopoly of Google and Facebook, which own the platforms that own the data. With the death of the cookie, publishers can finally profit from their own data.

Against the background of a weakened cookie, the Washington Post announced Zeus Prime, a proprietary platform for marketers to buy automated ads, in September 2019. Jarrod Dicker, The Post’s VP of Commercial Technology and Development, highlighted this as a revenue opportunity for publishers to come together and take on Big Tech. Vox similarly launched its ad-targeting data platform, Forte, in December.

Such a move was impossible when cookies were standard, since they gave cookie-owners (namely Google and Facebook) too much power over user data.

The death of the cookie opens up new opportunities

Cookies have been a useful crutch for advertisers, and learning to walk alone may be painful at first, but it’s the only route to greater independence and further reach in the long run. The final death of the cookie can give rise to better harvesting and use of first-party data, a new ad ecosystem that demands more creativity, a greater alliance between publishers and advertisers, and a brave new world for all stakeholders.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.