I have an opinion I wish to share that you almost certainly won’t agree with. (Not like that’s stopped me in the past)

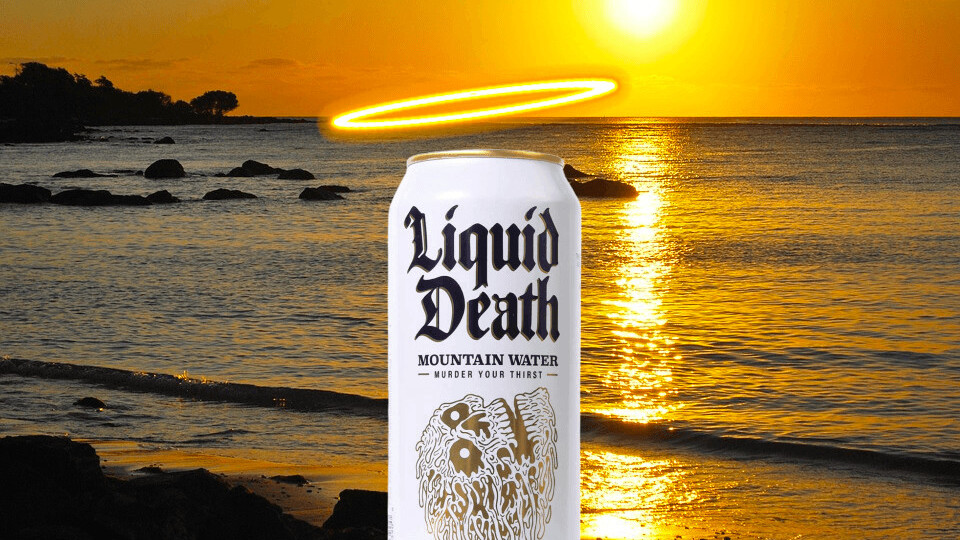

Mike Cessario, a former creative director at Netflix, recently raised $1.6 million from a swathe of top-tier investors, including Twitter founder Biz Stone, to launch a canned water company. The water, called Liquid Death, is sourced from Austria. Cans come plastered with an edgy, punk-style design and cost $1.83 per unit. Its slogan is “Murder your Thirst.”

The product came to global prominence after Business Insider profiled its founder. Of course, the Twitterverse didn’t waste any time shitting on the idea.

“Bro gets $1.6 million investment from other bros because existing bottled water threatens his punk rock masculinity,” tweeted Christopher Mims, a reporter with the Wall Street Journal. “Why. Would. Anyone. Buy. Let. Alone. Fund. Packaged. Water. It’s. 2019. Ffs,” argued exasperated author James Ball. “There’s no way the world lasts 12 more years,” said Daily Caller reporter Jessica Fletcher.

Bro gets $1.6 million investment from other bros because existing bottled water threatens his punk rock masculinity https://t.co/Lm2NA2cojQ pic.twitter.com/13hS29ZKVM

— Christopher Mims ? (@mims) May 7, 2019

Why. Would. Anyone. Buy. Let. Alone. Fund. Packaged. Water. It’s. 2019. Ffs.

Just put out a press release saying you hate the planet and save us all time, eh? https://t.co/MZI6Jbq2ae

— James Ball (@jamesrbuk) May 7, 2019

There’s no way the world lasts 12 more years https://t.co/Pk2pvJUkQ0

— Jessica Fletcher (@heckyessica) May 7, 2019

The most brutal reaction came from Buzzfeed News editor Tom Gara, who said: “This is one of those articles that would be such much [sic] better if it ended with the subject being hunted by dogs.” Ouch.

This is one of those articles that would be such much better if it ended with the subject being hunted by dogs https://t.co/qmOrHvZIRk

— Tom Gara (@tomgara) May 7, 2019

I understand the criticism. Although cans are superior to plastics when it comes to recyclability, any single-use item isn’t great for the environment. And then there’s the fact that an Ed Hardy version of water is a bit… silly?

So, here’s my take: Liquid Death is a good idea. It’s a bit like the Beyond Meat burger of alcohol. Externally, it looks indistinguishable from a normal can of craft lager, making it easier for teetotalers to blend in when stood in a crowded bar. For recovering alcoholics wishing to socialize without being pressured to drink, the product could act as a welcome camouflage, allowing them to sustain their relationships while opting out of something that’s utterly ubiquitous in Western society.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, an estimated 15.1 million Americans exhibit some kind of alcohol use disorder (AUD). A recurring theme in every bit of testimony I’ve read from an ex-drinker is that one’s social life inevitably suffers when you cut ties with the Devil’s nectar.

Previously reliable friends no longer want to hang out with someone who isn’t drinking, and without a few shots of bourbon coursing through your veins, bars and clubs no longer seem fun. Suddenly, every night is spent at home watching Netflix. Isolation starts to creep in.

This is a recognized problem. It’s for that reason why, in many cities around the world, entrepreneurs are opening so-called “dry bars.” These mimic the aesthetics of a bar, while serving non-alcoholic beverages and “mocktails.” These businesses serve to provide a sense of normality for those making a big change in their life, easing the transition to abstinence and potentially preventing a relapse, while also offering a temptation-free place to socialize.

To be clear, Liquid Death isn’t being marketed towards this demographic. According to a fascinating interview with Cessario in Business Insider, the primary inspiration for the product came from straight-edge punks. That is a very specific subculture within the punk scene that explicitly avoids psychoactive substances — typically nicotine, alcohol, and recreational drugs. Many also avoid engaging in casual sex and adhere to a plant-based diet.

And, for what it’s worth, I think that if Liquid Death explicitly said its product was aimed at teetotalers, it probably wouldn’t have attracted the mountains of criticism it did. Why does this matter? Because the murmurings of the Internet grapevine can be fatal to products when they’re in their earliest, most nascent stages.

Off the top of my head, the best example of this is the Palm Foleo, which was announced months before Asus released the EEE PC, and was a netbook before the term even existed. The negative reaction to the product, which came from pundits and bloggers and was partially centered on the device’s diminutive screen, convinced Palm to cancel the Foleo before it reached shelves.

I genuinely, hand-on-heart, think that Liquid Death is a good idea — or, at least, the concept behind it. It could help those recovering from addiction to maintain their social lives, thereby preserving relationships and giving a sense of normality.

I also think a lot of the criticism is misguided. Many are making the mistake of conflating a punk aesthetic with the cardinal sin of “broness,” ignoring the fact that some of the most iconic punks were women. Patti Smith, Siouxsie Sioux, and Vivienne Westwood all contributed immeasurably to the scene, to name just three. Of course, you could argue that expensive, VC funded water is the furthest thing possible from the notoriously anarchic and anti-establishment world of punk, but that’s neither here nor there. Liquid Death is obviously appropriating an identity.

On a more fundamental level, I’m glad that alternatives to alcohol are getting funded. $1.6 million for a water brand feels like a drop in the ocean (if you’ll pardon the pun) when compared to the multi-billion alcohol industry. In a weird way though, I hope Liquid Death isn’t too successful. If it’s going to serve as a camouflage for people who don’t drink, it’s best it stays underground.

That being said, isn’t it a shame that something like Liquid Death is necessary? If you don’t want to drink, you shouldn’t have to hide it.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.