This post originally appeared on the Crew blog.

Have you ever felt like all you do is check your e-mail? Well, you may not spend ALL your time checking your e-mail but you do spend about 28 percent of your time doing it. That translates into about 13-hours a week or 650 hours a year of e-mail checking.

For those of us who work in a job where e-mail isn’t our main responsibility, checking and responding to e-mails each day can take us away from our primary work, which results in less productivity.

In fact, our incessant need to respond to e-mails at work is actually making us miserable at work, but it doesn’t have to be that way. You have to reinvest in finding flow at work.

E-mail and productivity

Chuck Klosterman, writing for The New York Times, compared e-mail to a zombie attack—you keep killing them, they keep coming. Okay, so e-mails don’t actually turn us into flesh-eating-hell-beasts, but they do make us feel like we don’t have total control over our own lives.

- Workers switch tasks every three minutes, mostly due to e-mail (around 36 times an hour).

- The sheer volume of e-mails we receive makes us feel like we are out of control.

- We are afraid to use e-mail filters or other tools to help us handle our e-mail because we don’t want to feel out of the loop.

That, is a recipe for unhappiness and distraction.

Researchers at the University of Chicago and Microsoft decided to look into how e-mail disrupts our work day by logging workers interactions with their computer and monitoring their tasks.

Say you have a primary task, like working on a report. Then you receive an alert telling you that you have a new e-mail (that’s a diversion). Each time we experience a disruption at work we go through what is called an interruption life cycle, which looks like this:

Not only does e-mail hinder our ability to accomplish the essential aspects of our workday it also contributes to the overall stress we feel about our job. Even going so far as to impact our ability to maintain and develop good relationships at work.

“Email can be a superficial blanket that distances you from real relationships where you’re really working together.” —Study participant

Would these problems go away if people didn’t have access to e-mail? Well, one study wanted to look into what would happen if they did just that.

Researchers at the University of California, followed around 13 information workers. The study logged workers computer interactions, stress levels, and also had the workers respond to a series of questionnaires. The purpose was to find out how people would use their time if they weren’t allowed access to their e-mail.

“Without email, our informants focused longer on their tasks, multitasked less, and had lower stress.”—Researchers; Mark, Voida, & Cardello

It’s important to point out here that for these study participants, in fact in all instances above, e-mail was a secondary function or task of their employment. There are many people who respond to e-mails as part of their primary work.

The point here is to understand that we should be focusing on our primary tasks at work and when we don’t, we end up distracted, less happy, and less productive. The key, no matter what your job, is to find flow.

Finding your flow

Our productivity largely hinges on the kind of work you are doing and how motivated you feel about that particular task. For us to really feel motivated and accomplished at work, we have to enter a state of deep work (or flow).

Cal Newport is an author and blogger who writes about the concept of deep work. He defines it as:

“Cognitively demanding activities that leverage our training to generate rare and valuable results, and that push our abilities to continually improve.”

For Newport, the benefits of deep work are as follows:

- Continuous improvement of the value of your work output.

- An increase in the total quantity of valuable output you produce.

- Deeper satisfaction at work.

You know when you feel like your brain is going to explode from how hard something is, but you just keep hacking at it until you get it? You do it because it’s a rush, and a challenge, and you just know you have to finish something, and you won’t even breath one single breath until you do? Then when you finally finish it and you are all like:

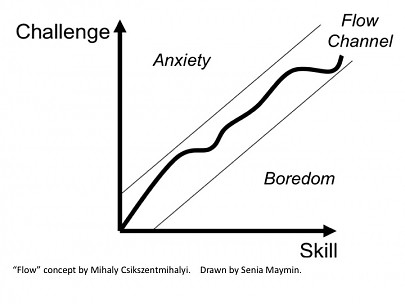

In psychology this is called flow—a state of effortless concentration. We have trouble achieving it because we are usually trying to find a balance between challenge and skill. When a challenge exceeds our skill level, that breeds anxiety. When there is far too little challenge, we are bored.

Here are three other things you can do to help improve your chances of entering flow (thereby making the most out of your time spent at work):

Eliminate obstacles

There are plenty of obstacles that stand in our way of a flow state. Workplace interruptions comprise a large majority of them. The average worker experiences at least 87 interruptions each day. Some advice from the Harvard Business Review about how to get into flow? Try not to check your e-mail until you’ve accomplished the most important task of your day.

If e-mail is your most important task of the day, respond to e-mails that will only take one to two minutes to complete first. Set aside the more involved e-mails in an ‘action folder’ and make sure you respond to them when you can devote the right amount of time and mental energy (this actually goes for everyone).

Set clear goals

If you don’t know what you want to achieve you will not achieve it. I could write a dissertation on this with myself as the primary case subject. It’s not enough to just have a goal in mind, you have to be as specific as possible about what that goal is and how you are going to achieve it.

Write down what success will look like, what failure will look like. If you want to find flow, you need to define these things for yourself so you can know when you achieve them.

Note your progress

So much about finding flow, indeed staying motivated in general, is about taking the time to acknowledge what you have done well. We either assume other people will notice, or that it’s not important enough to take time out of our schedule to say, ‘Hey, I did pretty good on that thing damn it.’

Even small wins motivate us. Writing down and crossing off items from your to-do list can help you measure progress and take advantage of those small wins.

Seriously, the more difficult something is, the better we feel about it once its completed. Challenges present us with an opportunity to learn a new skill, but they also allow us to see the fruits of our hard work.

For me, finding my flow means I’m not responding to every e-mail that comes to my inbox right away. Instead, I focus on my writing and research and turn off e-mail notifications until I complete my primary work. This helps me center my focus on what really matters.

When we find flow, our workdays seem to fly by. That’s one of the many benefits of focusing on the part of your job that you find challenging and enriching. Find ways to challenge yourself, keep focused on your primary task, and stop making time for distractions.

Read next: 3 Gmail tricks that can save you hours every week

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.