Lytro’s Illum, the first professional light field camera, will be available at consumer outlets worldwide and will ship all pre-orders on Friday, August 1. The camera retails for $1599 and is available in the US from Amazon, Best Buy, Target and B&H.

The camera combines a unique mix of 3D graphics and computational photography to produce distinctive “living pictures” that can change focus, depth of field, and perspective tilt at a viewer’s command. It’s targeted to professional photographers and enthusiasts keen to experiment with alternative photographic techniques and interactive storytelling.

The refocus and perspective shift features offer new opportunities to convey a narrative or record a scene. Living pictures present a brand new visual experience — not quite photo and not quite video, but something of a mix where the discretion of what to see and when is in the viewers’ hands.

This is my first shot with the Lytro Illum.

The advantage for viewers is that they can see different parts of the story at will. The advantage for shooters is that they don’t have to worry about precise focus at the time of capture.

Light field technology is not designed to replace traditional DSLR cameras — though Lytro CEO Jason Rosenthal thinks it eventually will — but rather to complement and offer an alternative dimension to the current crop of digicams.

A depth shot of bath salt bins at Pier 39 in San Francisco.

Next generation tech

The Lytro Illum records depth and focus in a different way than DSLRs and smartphones. Instead of a sensor recording the color and intensity of the combined light, an array of lenses in front of the light field sensor enables it to record the color, intensity, and direction of individual light rays.

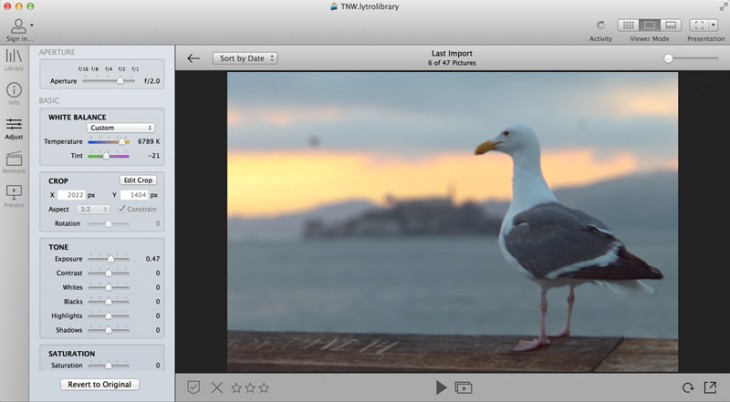

The Illum’s 40 megaray customized sensor (capturing 40 million rays) works together with the camera’s fixed 8x zoom lens to offer a 30 to 250mm range. The aperture is always fixed at a wide f/2.0, however since the Illum captures 3D data, the effective aperture range is commensurate with the 2D equivalent of f/2.0 to f/16. The lens autofocus feature zeroes in on the subject, shows you the refocus range in the frame, and gives you a starting point for your composition.

Seagull contemplating Alcatraz Island (Credit: Josh Anon)

A four-inch, angled, backlit touchscreen LCD provides plenty of room for fingertip focus and composition, while the Illum’s 1/4000 of a second maximum shutter speed makes it a natural for high-speed photography and sports.

Lytro does not advertise megapixel count because with light field photography, printing is beside the point. However, for the record, the conversion from magarays to megapixels amounts to roughly a 4-megapixel range with prints of about 8 x 12 or 16 x 20 inches.

The camera’s operating system is built on a version of Android with the kind of Qualcomm Snapdragon 800 CPU processor found in devices like the Samsung Galaxy S5 or the HTC One M8. It has wireless capabilities to connect with mobile devices, a removable battery, an SD card slot and a USB 3.0 port. It also accommodates accessories like external flash and tripods.

Starlings

In the hand

I was able to test out a pre-production Illum and here are my initial impressions.

Comparative weight depends on what you’re used to. At 2.07 pounds of matte black magnesium and aluminum, the Lytro is a heavy camera compared to some late-model DSLRs and mirrorless interchangeable lens models targeted to the enthusiast crowd. But for the pros who tend to carry heavier and bulkier gear, the Lytro will weigh in on the light side.

The camera measures 3.4 x 5.7 x 6.5 inches (86mm x 145mm x 166mm), and is roughly comparable in dimension to many standard DSLR bodies. As a fixed lens camera though, it’s more compact than many pro models sporting high-end lenses.

The Lytro has a minimal number of physical button controls and a fair number of touchscreen menu controls: You can use the on-screen menu bar to adjust shooting mode, ISO and more. Exposure compensation and bracketing controls are available, while your specs are clearly visible in the information bar at the bottom of the display.

Light field photography requires a different composition method, but the Illum’s built-in software, with its orange (far away) and blue (close up) color-coded depth overlay, gives real-time feedback on which elements in the scene are within refocus range and where they are situated relative to each other.

The indicators on the LCD screen instantly reminded me of Ansel Adams’ zone system for exposure, and I like to think about light field in-camera scale as an analogous zone system for depth. Once you start walking around with a Lytro, you immediately start thinking in terms of depth, but don’t make the mistake of discarding your 2D composition principles — you’ll need both to get your best shots.

In bright sunlight, be sure to crank up the screen brightness so you can actually see the colored indicators. Once I did that, I never had a problem seeing the display and thus establishing scene depth.

To shoot with the Illum, keep in mind that you can change the focus of the finished image as you view it on screen. As you shoot however, first choose a center of focus in the scene to serve as the point around which the picture will refocus best — either tap the screen to focus or use the camera’s autofocus feature.

With a camera of two pounds that you’re positioning away from your body to look down into a live view — not the traditional way of composing through a viewfinder — you have to be ready for that weight and space out your shots accordingly. Holding the camera in position for too long got my hands tired. But that may have been due to my unfamiliarity with the camera and getting used to the technique of measuring and adjusting the depth of the photo as well as determining the main area of focus and then considering composition.

Even though the camera is forgiving in terms of focus, you still have to focus in the near and far view to get a dynamic living picture. Here, the Lytro button is your friend, giving you the depth reading that helps you gauge the relative focus of objects in the frame. If you do not have a combination of near and far elements, the final image won’t have enough points of interest, and thus tapping the finished picture to change the depth of field will not tell a vibrant story.

It took a few hours to get used to not only thinking in depth but actually judging depth properly. But if you are wrong, the camera display quickly lets you know, at which point you either change your focus or zoom in or both.

For macro shots, you can actually touch the object with the lens as you focus. Subjects that are almost flush with the lens are in focus and the camera lets you refocus on other objects nearby.

Viewing live pictures

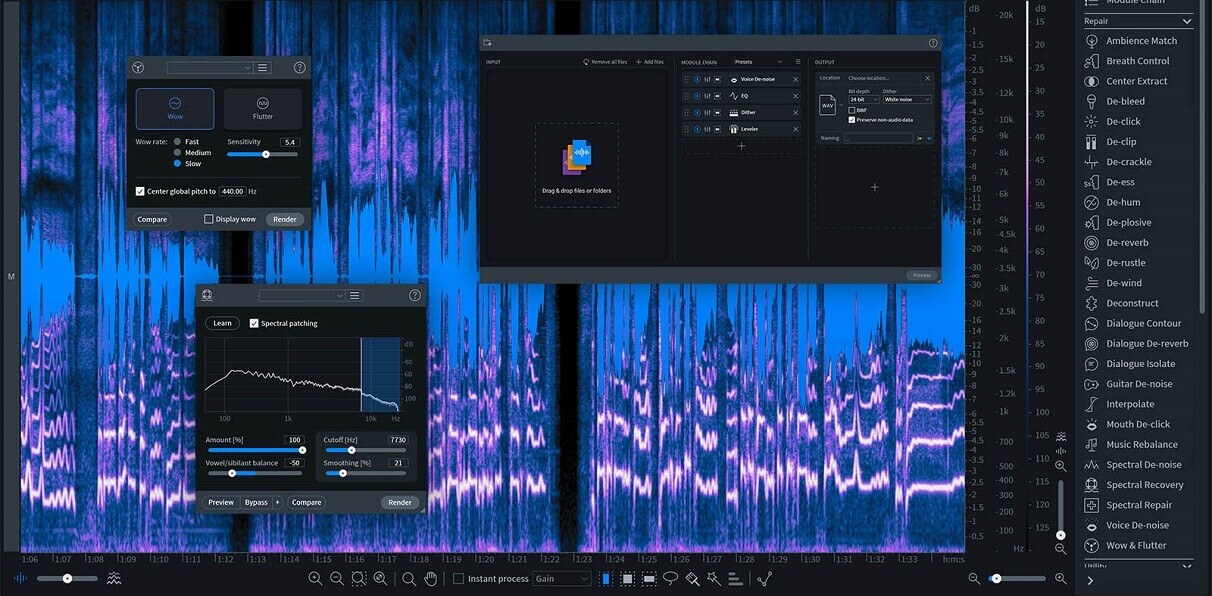

The Illum ships with Lytro Desktop, software that lets you import, customize and share your living pictures. A beta version of the software I saw allowed for many classic camera edits that photographers are used to such as exposure, contrast, highlights, shadows and more.

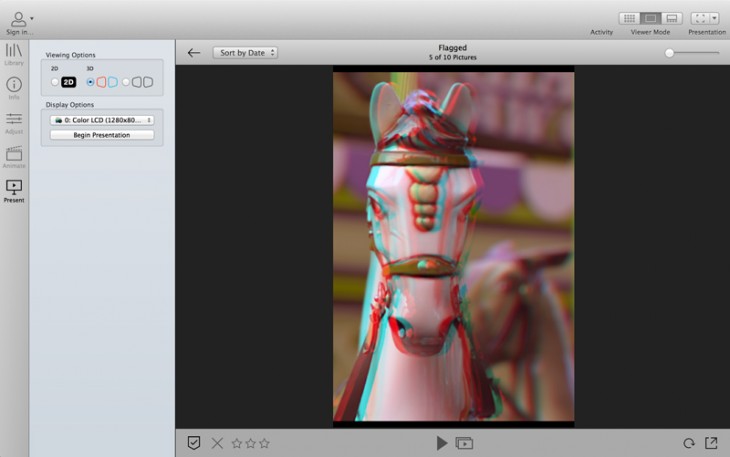

You can adjust aperture, tilt and rotate the focal plane for cinematic animations or instantly view shots in 3D. When you’re done, you can share your shots on social networks or embed them online in an interactive player.

The software requires OS X 10.8.5 or later or 64-bit Microsoft Windows 7 or 8.

A social mobile app for the iPhone and iPad is also available, letting you see your own as well as community living pictures. A new feature lets you create videos that automatically pan in and out of a living picture.

Living pictures can be viewed on the Lytro site and the player is now supported by the 500px photo portfolio site.

Bottom line

Lytro images, unlike traditional 2D stills, depend on the viewer to do something besides passively view your photos — they need to tap to refocus, shift and tilt perspective or both.

Lytro Desktop software, apart from its photo management functionality, also allows users to export the living picture images as videos or 3D stereo images. Instead of a static image the viewer needs to touch in order to change focus, it can refocus and move automatically.

You can adjust aperture, tilt and rotate the focal plane for cinematic animations or instantly view shots in 3D. When you’re done, you can share your shots on social networks or embed them online in an interactive player.

The software requires OS X 10.8.5 or later or 64-bit Microsoft Windows 7 or 8.

A social mobile app for the iPhone and iPad is also available, letting you see your own as well as community living pictures. A new feature lets you create videos that automatically pan in and out of a living picture.

Will shooters and viewers change their habits in order to accommodate the new living pictures as a more elaborate and interesting storytelling medium? While only time will tell, I believe that given the vast shift toward viewing images exclusively online, living pictures are a natural evolution of the photographic genre and that as long as viewers needs only tap, swipe or move a mouse — or just view an animated movie — that viewers will adopt the light field technology as a natural extension of photography.

All photographs and featured image (c) Josh Anon. Living pictures (c) Jackie Dove and Josh Anon as noted. The entire slate of living pictures shot for this story can be viewed online.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.