It’s difficult to pinpoint the first commercially-successful ebook, but many would give a nod to Stephen King’s novella Riding the Bullet. Released exclusively online in March 2000, it was purchased for $2.50 by 400,000 King fans in the first 24 hours, jamming the servers of one of the vendors providing it. It would go on to garner over half a million downloads and bring in $500,000 in revenue. “eBooks are here to stay,” one industry website said. “This revolution has well and truly begun.”

It’s difficult to pinpoint the first commercially-successful ebook, but many would give a nod to Stephen King’s novella Riding the Bullet. Released exclusively online in March 2000, it was purchased for $2.50 by 400,000 King fans in the first 24 hours, jamming the servers of one of the vendors providing it. It would go on to garner over half a million downloads and bring in $500,000 in revenue. “eBooks are here to stay,” one industry website said. “This revolution has well and truly begun.”

Despite such rosy proclamations, ebooks failed to gain much traction for several years. While in college, I used to participate in online message boards geared toward professional writers, and for most authors, ebooks were only one step above vanity publishing. An ebook publisher is where you went when a real publisher had rejected you. Of course with the launch of the Kindle, iPad, and other ebook readers, the medium has finally hit its stride and is commercially viable. In July of last year, Amazon announced that sales of Kindle ebooks were outperforming its hardback inventory. And just a few days ago it made another announcement that ebook sales had surpassed paperbacks as well.

But even with the commercial success of epublishing, Stephen King’s novella still remains one of very few examples of a widely-sold work published exclusively as an ebook. If you peruse through the top 100 selling Kindle books in the Amazon store, nearly every title has a corresponding print edition. Print, it turns out, still lends an ebook its credibility.

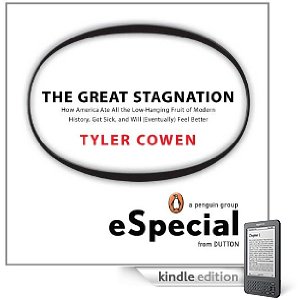

Perhaps this is why I was surprised to read recently that a famous economist had published an ebook to widespread critical acclaim. Tyler Cowen is a professor at George Mason University and the co-creator of the popular economics blog Marginal Revolution, which receives over 30,000 pageviews daily and has more than 100,000 RSS subscribers.

A few weeks ago, the publisher of his print books released The Great Stagnation, an ebook available in several downloadable formats. Almost immediately, discussion of the book began breaking out in mainstream venues; Ezra Klein at the Washington Post reviewed it. A New York Times blogger interviewed Cowen. The Economist and Wall Street Journal covered it.

A few weeks ago, the publisher of his print books released The Great Stagnation, an ebook available in several downloadable formats. Almost immediately, discussion of the book began breaking out in mainstream venues; Ezra Klein at the Washington Post reviewed it. A New York Times blogger interviewed Cowen. The Economist and Wall Street Journal covered it.

The book is short by conventional standards — a mere 15,000 words, the size of a long magazine article — and this, in part, factored into Cowen’s decision to forgo print. “I thought there was an important niche for books that are exactly the right length,” he told me in a phone interview. “But I also thought back to the 17th century to the origins of economics, and at that point in time, the publishing costs were low, there weren’t really publicity costs, and you had all these pamphlets. And they were about the same length as The Great Stagnation. So I thought there was something natural about the human attention span that lends itself to that length.”

But with the short length came several considerations: printing costs, distribution, whether book stores would stock it. It didn’t take long for Cowen to decide that an ebook edition would be appropriate. Dutton, the publisher that had published his previous books, was open to the idea.

Putting out an ebook with a major publisher has its similarities and differences compared to distributing a print edition. Cowen said the actual editing and pre-production of the book was the same, with obviously less emphasis on the front cover design. The promotion, however, was different. The idea of a print review copy that you can mail out to book reviewers doesn’t exist. And your target audience must be at least tech savvy enough to download the work.

One advantage Cowen has with his ebook is the popular blog he can use to promote it. “It makes a huge difference,” he said. “First you have a built in audience, your readers. But secondly, even people in the mainstream media, financial journalists for instance, have been reading me. They may or might not like me, but they’ll at least say to themselves, ‘There’s some chance this guy’s worth listening to. I’ll buy it, I’ll read it, whatever.”

Cowen has no idea how well the book is selling, but presumably the widespread coverage in major outlets will lead to more sales. But if the book is commercially successful, it wouldn’t be unfathomable for Dutton to decide it wants to release a print edition. Why restrict its availability if it hinders the movement of more units? “First I’d really want to see how the ebook does,” the economist said. “It’s 15,000 words, and what that even looks like in print, I’m not sure. I really think it works as an ebook, and have plenty of other books that exist in print, and to have one that’s just an ebook would be fine with me. Ideas like that tend to be at the discretion of the publisher and the terms of the contract, and even though the author is consulted, if the publisher wanted to do it, I’m not sure I would forbid it. But I don’t think it’s the model for me. The model for me is to focus on content and provide it in the formats that readers want. Unlike a lot of writers, I have a job as a professor, so I don’t have to sit back and think, ‘If this book doesn’t sell am I out on the street?'”

So in the end, it seems that the reason a famous economist decided to forgo a print edition of his book was, in part, because he could afford to.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.