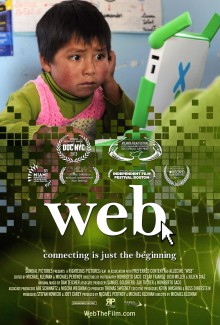

In keeping with this year’s Social Media Week theme of “Reimagining Human Connectivity,” filmmaker Michael Kleiman has released WEB, a documentary that takes a close look at the One Laptop Per Child rollout in Peru while examining the larger social implications the Internet will have as it spreads to new populations around the world.

The micro and macro threads that WEB follows make it a fascinating film. Interviews with academics, technologists and entrepreneurs tackle the subject on an intellectual level, while watching the excitement of the children as they start using their laptops adds a vital emotional dimension.

WEB has been making its way around the film festival circuit, but this week is the first time that it’s available on iTunes, Google Play and Amazon Instant Video. Interviewees include Internet pioneer Vint Cerf, OLPC founder Nicholas Negroponte, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales, Foursquare CEO Dennis Crowley and “Cognitive Surplus” author Clay Shirky.

The OLPC project has faced heavy criticism over its effectiveness and execution, and some of those concerns appear justified in the film. The foundation has lost much of its early momentum, but it does continue to operate. While Kleiman’s overall portrayal of the OLPC comes across as positive, he doesn’t shy away from showing the technical challenges and lack of training that have plagued the endeavor.

A scene where children collaborate to create the Spanish Wikipedia article for their small town is as powerful as the scenes of technicians fiddling unsuccessfully with the equipment are uncomfortable. If anything, WEB corroborates my impression that OLPC is a well-intentioned, but deeply flawed, project that sometimes manages – when it actually works – to change the lives of ordinary people in remote places.

As the film progresses, Kleiman inserts himself more into the film. He starts out as an observer of the characters, but eventually develops a close friendship with the children and their parents. You could argue that his presence ends up affecting the results of OLPC. For instance, at one point he tries to use his own generator to power an OLPC router, but his equipment ends up breaking it.

I’m not one to insist on objectivity in a documentary, so Kleiman’s own part in the film works for me. The movie is stronger for it because it directly addresses the tension of a foreigner living in the villages instead of awkwardly ignoring it. The friendships he builds get swept up into the larger theme of the role the Internet plays in making us more – or sometimes less – connected.

Coinciding with this week’s release, WEB has shared with TNW two extended scenes that didn’t make it into the film. In the first clip, Vint Cerf reminisces on how the Internet came to be. Cerf helped come up with the protocol that enabled discrete networks to communicate with each other.

Looking ahead to the future of the Internet, Cerf mentioned a number of trends, such as the rise of connected appliances and new devices; voice commands and instantaneous translation; interplanetary networks for scientific explorations; and increased risk factors and privacy implications.

In the second clip, Clay Shirky expounds on concepts he describes in Cognitive Surplus. New Internet-powered industries like the sharing economy advance Shirky’s theory that technology and improved communication enable us to use resources more efficiently.

“The resources are the same resources they were yesterday, but today we’ve got a community that’s willing to manage it together,” he said.

Interview with the director

We spoke to Kleiman to learn more about his inspiration for the film. He first got interested in the topic after reading Robert Wright’s book Nonzero, which portrays evolutionary history as the advancement of wider webs of interdependence.

“OLPC struck me as an embodiment [of that idea] because it’s bringing more voices to the table, to this web of interdependence,” he said. “That was the jumping off point.”

Kleiman acknowledged that opinions about OLPC are polarized, with people thinking it’s either a failure or “the greatest thing that ever happened.”

“What works about OLPC is people really have the desire for technology. I thought I might see a pushback or a resistance to the technology, but at least what I saw was, for the kids and the parents, a desire.”

Researchers have questioned whether OLPC produces actual educational gains, but Kleiman noted that just getting exposure to computers has value on its own in helping prepare students for higher education and the workforce.

“The challenges that I’ve seen and come through in the film are just the technical challenges,” Kleiman said. “My computer and Internet breaks all the time and I’ve got a really easy fix: go to the Genius Bar, call up Comcast. When you’re in the middle of the Amazon, it’s not as easy. The other part that has been a real weakness for OLPC has been the teacher training.”

He added that he’d like to see students learn to program and understand how the machines work, which would require instruction beyond just letting them figure things out on their own.

When I asked what Kleiman learned from the experience, he talked about the interest that people have in understanding what’s going on in other parts of the world and the desire to be remembered:

One theme in the film is that people there were constantly asking me not to forget them. There’s a meaning that comes from knowing there’s someone far away that knows you and is thinking of you. In this age, it’s impossible for me to think about forgetting someone because I see their every move on Facebook, there are so many other ways to remind us of them.

Kleiman said he made the film because he “had no idea” what was going to happen next with the growth of the Internet. The film doesn’t necessarily set out to answer that question. The world seems headed toward global connectivity, but the effects will be unpredictable.

Kleiman said he made the film because he “had no idea” what was going to happen next with the growth of the Internet. The film doesn’t necessarily set out to answer that question. The world seems headed toward global connectivity, but the effects will be unpredictable.

So is the Internet a basic human right? Even within the film, there’s an ongoing debate. Vint Cerf has called it a “civic right,” similar to a horse and buggy in the past. Meanwhile, A Human Right founder Kosta Grammatis asserts in his interview that the Internet is more than just the hardware and software technology that enables it. Instead, it’s a “digital civilization” that global citizens have a right to access.

For his part, Kleiman said he’s comfortable talking about the issue in terms of governments “not having a right to disconnect.” Regimes that cut their citizens off from the Internet are violating their rights, but global residents don’t necessarily have an inherent right to get online.

Kleiman said that his hope for the film is for it to be a “catalyst for a global pause or reflect about the type of Internet we want to create and how we collectively want to use technology to shape our society.” Partnering with Social Media Week to screen the film in seven cities helped him to start that conversation. He concluded:

As more and more people are brought online how does that change the way all of us think about how we relate to each other? How does our sense of community change, shared culture, even our understanding of simple things like friendship? As the Internet spreads to the furthest corners of the world, these are issues and concerns that all of us will need to grapple with together. The film’s goal is to highlight that tension and SMW provides a really appropriate space to do so.

If you’re reading this, you’re already one of the lucky few billion people with access to the Internet. WEB helps remind us to be thankful for the benefits that connectivity has made possible, cautious about the potential pitfalls, and generous in our efforts to bring this amazing technology to other global citizens.

➤ WEB [iTunes, Google Play]

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.