Humans generate more data on Facebook in a single day than exists in all the books ever written combined. That’s not even counting Google Search trends, Amazon and Alibaba’s shopping insights, and Microsoft’s gleanings from having Windows installed on a gazillion devices. Data, unlike gold and oil, is a nearly unlimited resource.

So why aren’t we getting paid for creating it?

In return for this data — which provides the primary source of income for social networks like Facebook — we’ve developed new addictions, watched national elections fall under the influence of foreign entities, and unwittingly participated in the training of autonomous technology that’ll likely disrupt the vast majority of industries humans currently work in. But we haven’t gotten paid.

Facebook, on the other hand, has: it’s worth nearly half a trillion dollars.

Does this mean we’re all a bunch of cows giving the milk away for free? If our personal information is worth so much how come all we’re getting in return for it is status updates and a never ending stream of advertisements?

Perhaps you don’t use Facebook; maybe you’re too busy or social media just isn’t your thing. But the chances are pretty good, if you’re reading this, you use Amazon, Google, or LinkedIn. Either way, the vast majority of people on this planet are giving data away for free.

And, for now, that’s fine because we’re sure that we’re getting something out of it. The people asking questions and raising red flags often get drowned out in the sea of likes, shares, and memes.

Last year, when congress called social media companies to the figurative “principal’s office” to discuss Russian election interference, Twitter and Facebook only begrudgingly participated. People, by and large, aren’t interested in calling these companies to task for how they handle our personal info.

And currently the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals is preparing to help settle a dispute over data (our data) between Microsoft’s LinkedIn network and a tiny company you’ve probably never heard of called HiQ.

It’s excusable if you weren’t aware of the legal battle. As a dispute over data, it’s not a high-profile case with drama and intrigue. But it could have huge implications throughout the technology world. Basically LinkedIn believes it has a right to deny 3rd parties, like HiQ, from scraping data which was intentionally set by users to be made publicly available. HiQ says the data doesn’t belong to LinkedIn anyway.

So who actually owns the data?

Before we can answer we have to discuss why this information is so important and valuable.

1. Advertising makes up the bulk of Google and Facebook’s revenue. That’s a lot of money and it all comes from the unique ability tech companies have to provide detailed insights and demographics.

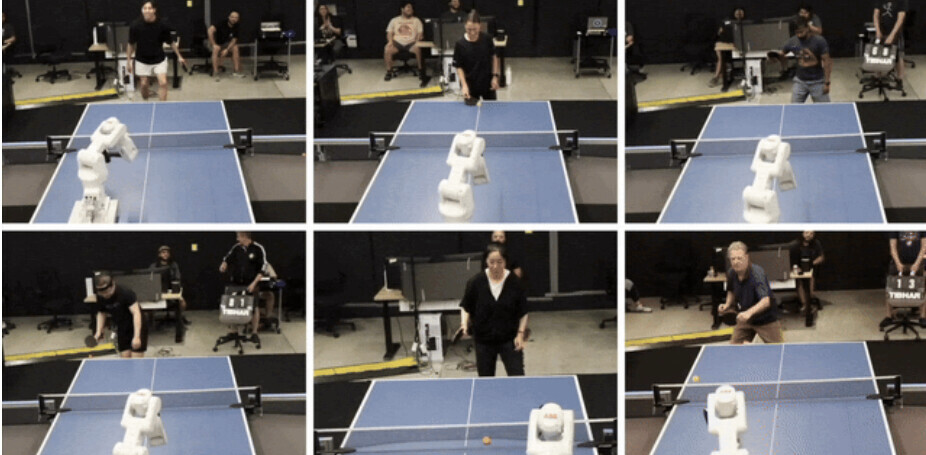

2. Artificial intelligence uses data like humans use blood, and there’s no such thing as too much. Every neural network needs anywhere from thousands to hundreds of millions of pieces of individual data to train. As AI becomes integrated in just about every industry the need for data is only going to increase.

3. As automation replaces humans in the workforce developers and businesses will slowly lose a source of uninhibited data: monitoring human employees. This means the need for data is likely to increase due to both demand and scarcity.

Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind when it comes to this type of data, personal information, is that it can’t be manufactured. Companies can try and fake it or counterfeit it, but the real value of our personal information is that it’s ours.

We spoke with the head of Carnegie Mellon University’s philosophy department, Professor David Danks, who said there were, generally, two ways of looking at data:

In the EU data is an extension of the person. It’s not like a product, but an actual part of that person. So people in the EU own their data. But here in the US, we have very much moved to a model where data belongs to the company.

What happens now?

Facebook and Google ballooned into the giants they are now because they tapped into a brand new natural resource (personal information) before most people realized it had value. And now AI is changing the way we, as a society, value data all over again.

Letting Facebook, for example, sell our data without giving us a penny of those profits, in retrospect, feels a lot like being the guy who bought a pizza eight years ago for the low price of 10,000 bitcoin: today that’d be a 8.8 million dollar pizza.

Some experts argue levying a data tax on major technology companies could pay for a universal basic income. Whether or not you believe that’s a good idea doesn’t change the fact it’s further indication our data is valuable.

But, to stretch the previous analogy, now that we’ve given away so much milk for free how do we start charging for it? It’s probably unrealistic to expect Facebook to put us all on the payroll tomorrow. And there’s a pretty good chance your “share” of the data pool wouldn’t amount to much. We’d have to get each of the big data companies to cut us checks before we could all quit our day jobs.

And it’s going to be difficult to put a price on our data (though, it turns out TNW did just that and the price was $480). Plus it’ll be even harder to track and enforce the proper licensing of data. If the government taxes big tech we have to trust that our government is looking out for citizens instead of corporations.

Yet, if we leave it up to Google and Facebook they’ll keep moving their billions around through various parent companies, offshore accounts, and whatever other tricks companies worth nearly a trillion dollars can come up with. We’ll never get back what our data is actually worth.

Ultimately, the only way we can decide who owns our data is by becoming picky with how we share it and demanding more transparency from the companies we allow to use it.

Maybe Google, Facebook, and Twitter will change the way they do business. Yet, more likely, a generation of people who’ve spent their entire lives in the age of social media will simply create a better platform.

After all, if you can get rich investing real money in cryptocurrency that doesn’t actually exist in the physical world, I see no reason why Google shouldn’t pay me to use its search engine.

Want to hear more about AI from the world’s leading experts? Join our Machine:Learners track at TNW Conference 2018. Check out info and get your tickets here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.