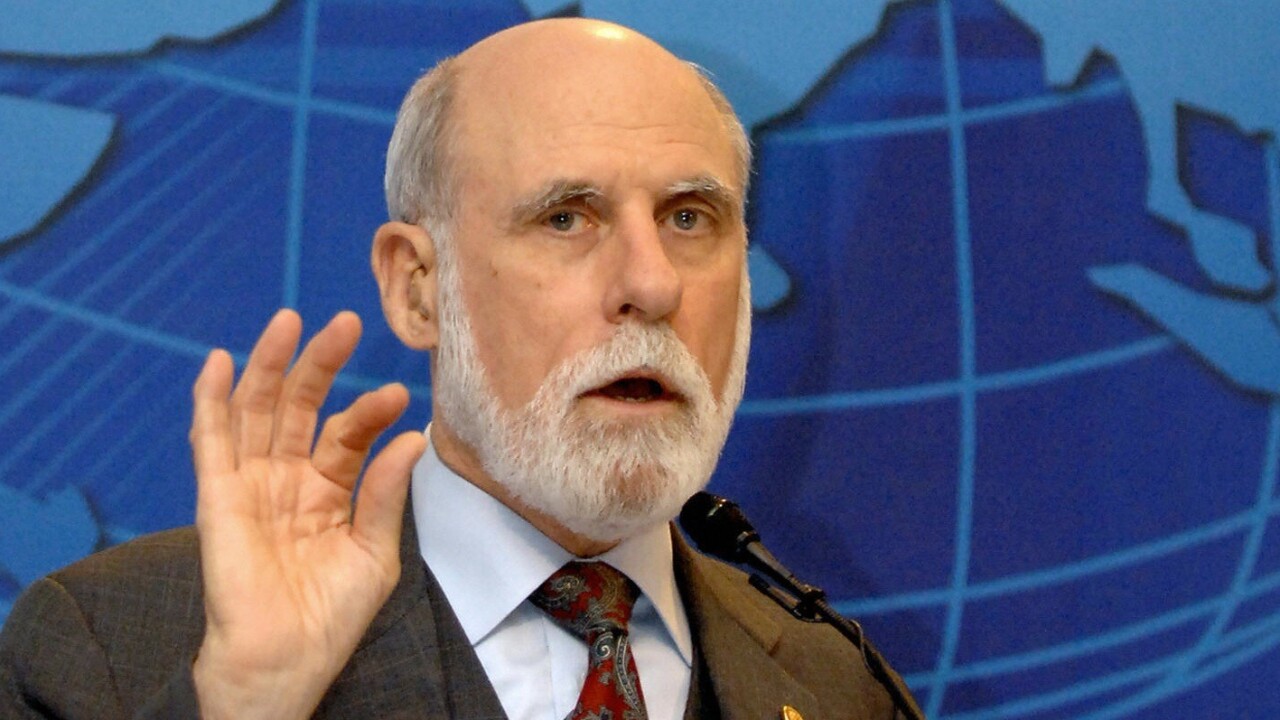

Few people have as much claim as Vint Cerf to the title “Father of the Internet,” but as the technologies he helped develop in the 1970s and ’80s become increasingly central to our lives, delighting us in ever more exciting ways, they’re also facing greater scrutiny by the intelligence services.

Cerf is currently based in the UK, from where as part of his role as Chief Internet Evangelist for Google he is acting as a spokesperson for the company on Internet policy issues across Europe, the Middle East and Africa. He spoke at the ScotlandIS Global Forum conference in Edinburgh yesterday, an event aimed at Scotland’s technology industry leaders.

To tie in with Cerf’s talk, we caught up with him on the phone to discuss PRISM, contextual tech and the future of the Internet.

Citizens of the Internet: Should national laws apply online?

The PRISM scandal (although Cerf thinks scandal isn’t the right word and prefers to describe it as a “brouhaha”) has thrown many people’s assumptions of what kind of privacy they can expect online into disarray, and with President Obama having spoken of the “tradeoffs” required between Americans’ privacy and their security.

However, the effects of US law are felt far beyond the 50 states. Many of the laws that influence PRISM-style spying operations hinge on a single nation’s legal structure, but can affect people in all sorts of places around the world. I’m in the UK but use mainly American Internet services and work remotely with a team based in locations all over the world. As I’ve noted before, I feel more like a citizen of the Internet than of the UK.

However, Cerf isn’t keen to entertain the idea that the Internet and our activities on it should exist outside of traditional nation state structures, even if we sometimes feel that they do.

“I think it’s attractive to have this certain fantasy that the virtual world that we live in is somehow hovering over the real world and isn’t connected to it. But the fact of the matter is that the way we create that virtual world is with pieces of equipment, hardware and software that exist in the real world. So we realize the virtual world in various geographic locations. So there is certain inescapable jurisdiction associated with that.

“So I think we should be a little careful about fooling ourselves that there isn’t the real world out there that has certain constraints and restrictions on it.

“You will recall The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. If you remember your history, that is what created the nation state and it created the notion of sovereignty. What has happened in the case of the Internet in particular, although not uniquely so, is that it has created an environment where boundary lines are blurred.

So, Cerf believes there is room for new international agreements that recognize the online space as ‘transnational’.

“The Internet doesn’t really know when it’s crossing an international boundary. It’s a virtual thing which links everything together. It’s transnational — I think it’s an important term to use. Not international but transnational. Now a consequence of this is that we can’t really say that the Westphalia notion absolutely applies.”

“I’ll give you an example,” says Cerf. “This is one that I am taking from a former French diplomat Bertrand de La Chapelle, who is a member of the ICANN board and an academic now, and for all practical purposes a reincarnation of an 18th century French philosopher. He makes the point that if there were a river flowing from country A to country B, and country A decided to dump all of its pollution into the river just as it goes into country B, that this would not necessarily be an example of a sovereign right that nation A has on the grounds that it’s taking an action that’s harmful to nation B.

“There are similar situations on the Internet where somebody attacks a person through the network, harming them even though the two of them are in different national jurisdictions. At this point we have to step back and say ‘We must be in a post-Westphalian environment where our actions in one country cannot be entirely protected on grounds of sovereignty.’

“Now in order to realize any of those notions we are going to have to have some international agreements that we collectively agree that certain actions are unacceptable and that we will collectively take steps to either prevent them or prosecute people who engage in them. And that is something which we have examples of now. Interpol is an example. Drug wars are an example. Anti-fraud measures are an example. Anti-terrorist measures are an example, especially where you are tracking financial transactions.

“So I mean you have examples where this need to deal with transnational events has been accommodated and I think the internet is going to be subject to same kind of treatment.”

Glass and contextual tech

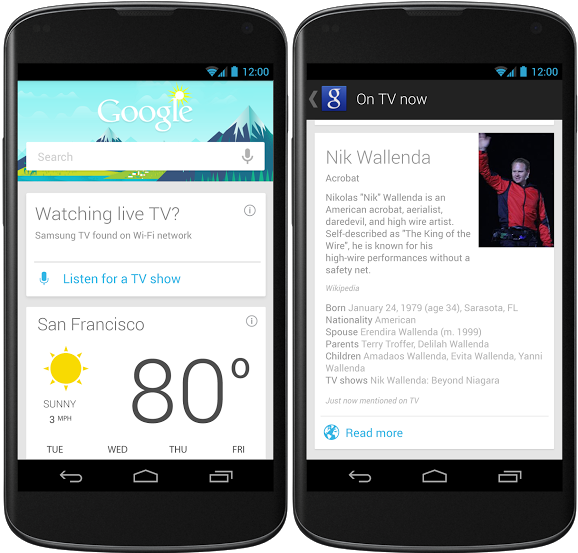

The past year has seen great leaps forward in both wearable tech and contextual technology that learns about you and offers up relevant information based on your location. Google is at the forefront of both of these trends with Google Glass and Google Now. As a Googler with a greater sense of historical perspective than just about any other at the company, Cerf is excited by the potential of both.

The past year has seen great leaps forward in both wearable tech and contextual technology that learns about you and offers up relevant information based on your location. Google is at the forefront of both of these trends with Google Glass and Google Now. As a Googler with a greater sense of historical perspective than just about any other at the company, Cerf is excited by the potential of both.

“I think what happens when you bring the computer into your environment where it sees what you see and hears what you hear is that you have the opportunity for very cooperative relationship. And this is an unusual opportunity to take advantage of the possibilities of artificial intelligence or at least extremely smart software.

“I’ll give you an example that doesn’t actually work right now but it is a sort of thing one might imagine happening in the future. Let’s imagine that we have a blind German speaker and deaf American sign language speaker and the two of them are wearing Google Glass. So let’s see what happens.

“The German speaker speaks in German. The Google Glass of the deaf user hears German, translates it into English and then shows it as captions in the Google Glass for the deaf person. The deaf person responds with sign language which the blind guy can’t see but his Google Glass does, translates the American sign language into English and then translates the English into German and then speaks German using the bone conduction audio system of the Google Glass that the blind person is wearing.

“Now we can do all of that except for the sign language interpretation which is actually pretty hard. But it’s not completely out of the question, with image processing and the like advancing as time goes on.

“So this is kind of an example how Google Glass becomes your partner in this common sensory environment and helps you adapt to things that you wouldn’t normally be able to. Google Now takes advantage of the same sort of thing because it sees what you see, it hears what you hear and knows where you are — a simple GPS system. And so it can now be responsive to questions that are related to context and it can even take initiative.

“For example, if Google Now knows what’s on your calendar and notices where you are and what time it is, it could say to you, ‘You should take an alternate route to get to this destination because there is a traffic problem over here’. Or ‘We would recommend that you take the tube because there is congestion everywhere.’

“There are a variety of things that one can imagine. Of course in the advertising context there is always a possibility of somebody saying ‘Well, if you walk down on the block a little further here, there is a lunchtime special at this little tiny restaurant.’ So once again it’s an opportunity to allow us to apply computing capability to our sort of immediate situation. And it’s the context which is quite exciting.

“Anyway. There is a variety of things that can happen and it’s the contextual opportunity, the thing which allows us to apply lots of computing cycles in the context of what you are doing or where you are or what is known about your current situation. That I find extremely powerful. I think there is just an endless number of possibilities waiting to be explored and implemented.”

Does the Silicon Valley ‘data silo’ trend hold back the potential of contextual tech?

Technology like Google Now is so effective because of how much Google knows about us. Imagine if such contextual technology could combine the deep knowledge that a number of different services have about you? Your Google location and search histories coupled with your Foursquare tips, Yelp ratings or Facebook friends list, for example.

However, there’s a trend away from open APIs in Silicon Valley – just look at how Twitter has pulled back a lot of the freedom it used to give to developers, while Google+ barely has an API to speak of. Will emerging contextual services be hampered by being subject to corporate data silos in a way that early ‘Web 2.0’ services weren’t? Think about how APIs helped the likes of Twitter and Flickr flourish early on. Cerf thinks it’s a matter of privacy.

“Let us imagine that the reason Google Now is capable of doing something useful is that it you have allowed it to access to have access to other things that you have done in the Google space,” Cerf says. “The idea that Google would allow that contextual information to go to somebody else, I think would fly in the face of the interest we both have in protecting your privacy.

“Now the other side of this coin is that Google also has a Google Data Liberation policy which says that that which is put into our system by your or for you — for example incoming emails, things like that — should be extractable from the system. You should be able to remove any of the data that there is and then repurpose it however you wish. On the other hand they don’t think you would want Google to arbitrarily and without your authorization, share data with other people.

“So here I think that it might be hampering in the sense that if Google information about your calendar or searches that you have done or the email that you have or the documents that you have, you probably would not want Google to arbitrarily and without your consent share any of that data with anyone else. So to the extent that that means that the various businesses that are trying to provide service to you can’t aggregate everything that is known about you by everybody. That’s probably in your best interest.”

The next great leap forward for the Internet

We couldn’t speak to a father of the Internet without asking him about what he thinks is the next great leap forward. It turns out that what’s exciting Cerf is something that has been talked about so much that some people have already grown skeptical of its true potential.

“To be trite about it I think the Internet of Things is really a big deal. It’s very clear that this is on its way, that appliances around the house, the office and your car and on your person are becoming Internet-capable. And this opens up some remarkable opportunities. One of them is the contextual kinds of opportunities we have been talking about. But I think it also leads to things like continuous monitoring of your physical state.

“You’re seeing Fitbit and other kinds of monitoring capability coming into play now. There is a very popular notion here called Quantified Self which here in the US translates into people whose genome has been fully sequenced, people whose physical condition is being monitored minute by minute with a variety of different measurements.

“These sorts of things are allowing us to observe the state of your health, state of your body, on a minute by minute basis. And that’s actually quite important because there is some medical conditions that won’t be detected because you went to the doctor once every 3 months and you know he took the blood pressure and temperature and that’s about it. But if you have continuous monitoring, you may actually be able to detect a serious problem very early on and do something about it.”

Also read: Internet pioneer Vint Cerf talks online privacy, Google Glass and the future of libraries

Image credits: JUNG YEON-JE/AFP/Getty Images, Wikimedia Commons, Google

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.