I recently won first place in the Nexar Traffic Light Recognition Challenge, computer vision competition organized by a company that’s building an AI dash cam app.

In this post, I’ll describe the solution I used. I’ll also explore approaches that did and did not work in my effort to improve my model.

Don’t worry — you don’t need to be an AI expert to understand this post. I’ll focus on the ideas and methods I used as opposed to the technical implementation.

The challenge

The goal of the challenge was to recognize the traffic light state in images taken by drivers using the Nexar app. In any given image, the classifier needed to output whether there was a traffic light in the scene and whether it was red or green. More specifically, it should only identify traffic lights in the driving direction.

Here are a few examples to make it clearer:

The images above are examples of the three possible classes I needed to predict: no traffic light (left), red traffic light (center) and green traffic light (right).

The challenge required the solution to be based on Convolutional Neural Networks, a very popular method used in image recognition with deep neural networks. The submissions were scored based on the model’s accuracy along with the model’s size (in megabytes). Smaller models got higher scores. In addition, the minimum accuracy required to win was 95%.

Nexar provided 18,659 labeled images as training data. Each image was labeled with one of the three classes mentioned above (no traffic light/red/green).

Software and hardware

I used Caffe to train the models. The main reason I chose Caffe was because of the large variety of pre-trained models.

Python, NumPy & Jupyter Notebook were used for analyzing results, data exploration, and ad-hoc scripts.

Amazon’s GPU instances (g2.2xlarge) were used to train the models. My AWS bill ended up being $263 (!). Not cheap. ?

The code and files I used to train and run the model are on GitHub.

The final classifier

The final classifier achieved an accuracy of 94.955% on Nexar’s test set, with a model size of ~7.84 MB. To compare, GoogLeNet uses a model size of 41 MB, and VGG-16 uses a model size of 528 MB.

Nexar was kind enough to accept 94.955% as 95% to pass the minimum requirement ?.

The process of getting higher accuracy involved a LOT of trial and error. Some of it had some logic behind it, and some were just “maybe this will work”. I’ll describe some of the things I tried to improve the model that did and didn’t help. The final classifier details are described right after.

What worked?

Transfer learning

I started off with trying to fine-tune a model which was pre-trained on ImageNet with the GoogLeNet architecture. Pretty quickly this got me to >90% accuracy! ?

Nexar mentioned in the challenge page that it should be possible to reach 93% by fine-tuning GoogLeNet. Not exactly sure what I did wrong there, I might look into it.

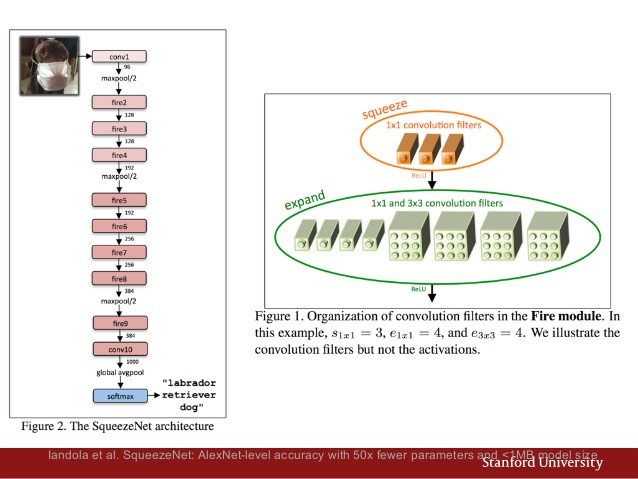

SqueezeNet

SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <0.5MB model size.

Since the competition rewards solutions that use small models, early on I decided to look for a compact network with as few parameters as possible that can still produce good results. Most of the recently published networks are very deep and have a lot of parameters. SqueezeNet seemed to be a very good fit, and it also had a pre-trained model trained on ImageNet available in Caffe’s Model Zoo which came in handy.

The network manages to stay compact by:

- Using mostly 1×1 convolution filters and some 3×3

- Reducing number of input channels into the 3×3 filters

For more details, I recommend reading this blog post by Lab41 or the original paper.

After some back and forth with adjusting the learning rate I was able to fine-tune the pre-trained model as well as training from scratch with good accuracy results: 92%! Very cool! ?

Rotating images

Most of the images were horizontal like the one above, but about 2.4% were vertical, and with all kinds of directions for “up”. See below.

Although it’s not a big part of the data-set, I wanted the model to classify them correctly too.

Unfortunately, there was no EXIF data in the jpeg images specifying the orientation. At first, I considered doing some heuristic to identify the sky and flip the image accordingly, but that did not seem straightforward.

Instead, I tried to make the model invariant to rotations. My first attempt was to train the network with random rotations of 0°, 90°, 180°, 270°. That didn’t help ?. But when averaging the predictions of 4 rotations for each image, there was improvement!

92% → 92.6% ?

To clarify: by “averaging the predictions” I mean averaging the probabilities the model produced for each class across the 4 image variations.

Oversampling crops

During training the SqueezeNet network first performed random cropping on the input images by default, and I didn’t change it. This type of data augmentation makes the network generalize better.

Similarly, when generating predictions, I took several crops of the input image and averaged the results. I used 5 crops: 4 corners and a center crop. The implementation was free by using existing caffe code for this.

92% → 92.46% ?

Rotating images together with oversampling crops showed very slight improvement.

Additional training with lower learning rate

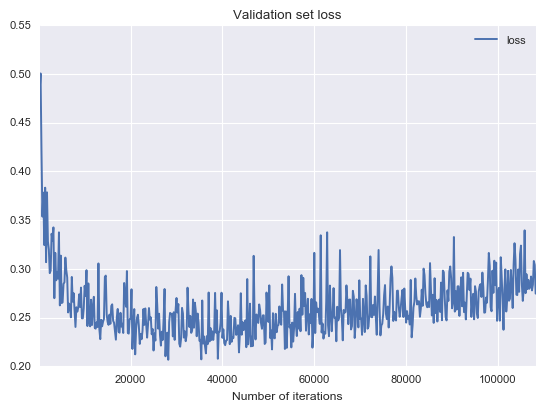

All models were starting to overfit after a certain point. I noticed this by watching the validation-set loss start to rise at some point.

I stopped the training at that point because the model was probably not generalizing anymore. This meant that the learning rate didn’t have time to decay all the way to zero. I tried resuming the training process at the point where the model started overfitting with a learning rate 10 times lower than the original one. This usually improved the accuracy by 0-0.5%.

More training data

At first, I split my data into 3 sets: training (64%), validation (16%) & test (20%). After a few days, I thought that giving up 36% of the data might be too much. I merged the training & validations sets and used the test-set to check my results.

I retrained a model with “image rotations” and “additional training at lower rate” and saw improvement:

92.6% → 93.5% ?

Relabeling mistakes in the training data

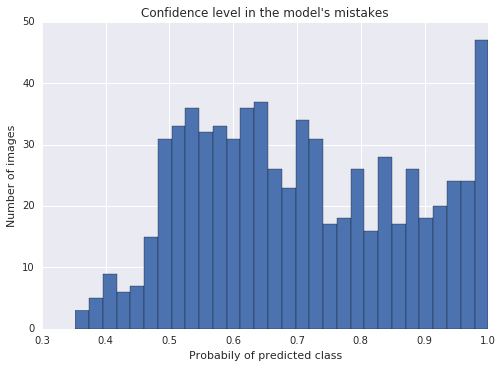

When analyzing the mistakes the classifier had on the validation set, I noticed that some of the mistakes have very high confidence. In other words, the model is certain it’s one thing (e.g. green light) while the training data says another (e.g. red light).

Notice that in the plot above, the right-most bar is pretty high. That means there’s a high number of mistakes with >95% confidence. When examining these cases up close I saw these were usually mistakes in the ground-truth of the training set rather than in the trained model.

I decided to fix these errors in the training set. The reasoning was that these mistakes confuse the model, making it harder for it to generalize. Even if the final testing-set has mistakes in the ground-truth, a more generalized model has a better chance of high accuracy across all the images.

I manually labeled 709 images that one of my models got wrong. This changed the ground-truth for 337 out of the 709 images. It took about an hour of manual work with a python script to help me be efficient.

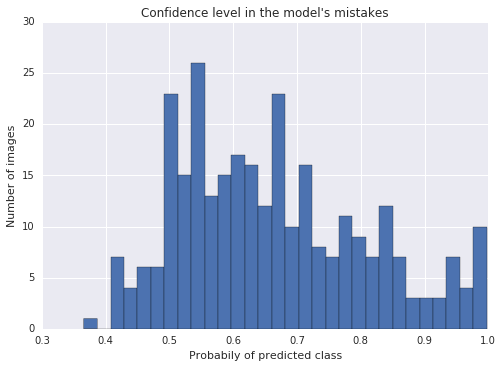

Above is the same plot after re-labeling and retraining the model. Looks better!

This improved the previous model by:

93.5% → 94.1% ✌️

Ensemble of models

Using several models together and averaging their results improved the accuracy as well. I experimented with different kinds of modifications in the training process of the models involved in the ensemble. A noticeable improvement was achieved by using a model trained from scratch even though it had lower accuracy on its own together with the models that were fine-tuned on pre-trained models. Perhaps this is because this model learned different features than the ones that were fine-tuned on pre-trained models.

The ensemble used 3 models with accuracies of 94.1%, 94.2%, and 92.9% and together got an accuracy of 94.8%. ?

What didn’t work?

Lots of things! ? Hopefully, some of these ideas can be useful in other settings.

Combatting overfitting

While trying to deal with overfitting I tried several things, none of which produced significant improvements:

- increasing the dropout ratio in the network

- more data augmentation (random shifts, zooms, skews)

- training on more data: using 90/10 split instead of 80/20

Balancing the dataset

The dataset wasn’t very balanced:

- 19% of images were labeled with no traffic light

- 53% red light

- 28% green light.

I tried balancing the dataset by oversampling the less common classes but didn’t notice any improvement.

Separating day & night

My intuition was that recognizing traffic lights in daylight and nighttime is very different. I thought maybe I could help the model by separating it into two simpler problems.

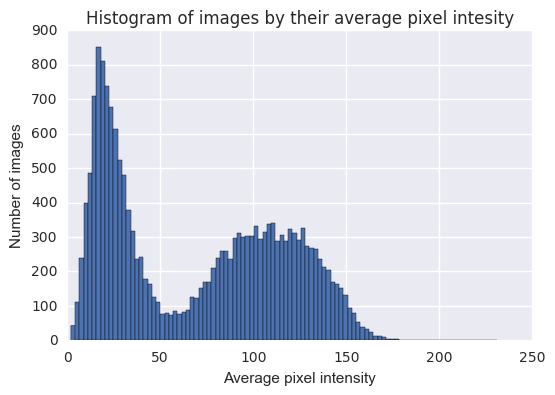

It was fairly easy to separate the images to day and night by looking at their average pixel intensity:

You can see a very natural separation of images with low average values, i.e. dark images, taken at nighttime, and bright images, taken at daytime.

I tried two approaches, both didn’t improve the results:

- Training two separate models for day images and night images

- Training the network to predict 6 classes instead of 3 by also predicting whether it’s day or night

Using better variants of SqueezeNet

I experimented a little bit with two improved variants of SqueezeNet. The first used residual connections and the second was trained with dense→sparse→dense training (more details in the paper). No luck. ?

Localization of traffic lights

After reading a great post by deepsense.io on how they won the whale recognition challenge, I tried to train a localizer, i.e. identify the location of the traffic light in the image first, and then identify the traffic light state on a small region of the image.

I used sloth to annotate about 2,000 images which took a few hours. When trying to train a model, it was overfitting very quickly, probably because there was not enough labeled data. Perhaps this could work if I had annotated a lot more images.

Training a classifier on the hard cases

I chose 30% of the “harder” images by selecting images which my classifier was less than 97% confident about. I then tried to train classifier just on these images. No improvement. ?

Different optimization algorithm

I experimented very shortly with using Caffe’s Adam solver instead of SGD with linearly decreasing learning rate but didn’t see any improvement. ?

Adding more models to ensemble

Since the ensemble method proved helpful, I tried to double-down on it. I tried changing different parameters to produce different models and add them to the ensemble: initial seed, dropout rate, different training data (different split), a different checkpoint in the training. None of these made any significant improvement. ?

Final classifier details

The classifier uses an ensemble of 3 separately trained networks. A weighted average of the probabilities they give to each class is used as the output. All three networks were using the SqueezeNet network but each one was trained differently.

Model #1 — Pre-trained network with oversampling

Trained on the re-labeled training set (after fixing the ground-truth mistakes). The model was fine-tuned based on a pre-trained model of SqueezeNet trained on ImageNet.

Data augmentation during training:

- Random horizontal mirroring

- Randomly cropping patches of size 227 x 227 before feeding into the network

At test time, the predictions of 10 variations of each image were averaged to calculate the final prediction. The 10 variations were made of:

- 5 crops of size 227 x 227: 1 for each corner and 1 in the center of the image

- for each crop, a horizontally mirrored version was also used

Model accuracy on validation set: 94.21%

Model size: ~2.6 MB

Model #2 — Adding rotation invariance

Very similar to Model #1, with the addition of image rotations. During training time, images were randomly rotated by 90°, 180°, 270° or not at all. At test-time, each one of the 10 variations described in Model #1 created three more variations by rotating it by 90°, 180°, and 270°. A total of 40 variations were classified by our model and averaged together.

Model accuracy on validation set: 94.1%

Model size: ~2.6 MB

Model #3 — Trained from scratch

This model was not fine-tuned but instead trained from scratch. The rationale behind it was that even though it achieves lower accuracy, it learns different features on the training set than the previous two models, which could be useful when used in an ensemble.

Data augmentation during training and testing are the same as Model #1: mirroring and cropping.

Model accuracy on validation set: 92.92%

Model size: ~2.6 MB

Combining the models together

Each model output three values, representing the probability that the image belongs to each one of the three classes. We averaged their outputs with the following weights:

- Model #1: 0.28

- Model #2: 0.49

- Model #3: 0.23

The values for the weights were found by doing a grid-search over possible values and testing it on the validation set. They are probably a little overfitted to the validation set, but perhaps not too much since this is a very simple operation.

Model accuracy on validation set: 94.83%

Model size: ~7.84 MB

Model accuracy on Nexar’s test set: 94.955% ?

Examples of the model mistakes

The green dot in the palm tree produced by the glare probably made the model predict there’s a green light by mistake.

The model predicted red instead of green. A tricky case when there is more than one traffic light in the scene.

The model said there’s no traffic light while there’s a green traffic light ahead.

Conclusion

This was the first time I applied deep learning on a real problem! I was happy to see it worked so well. I learned a LOT during the process and will probably write another post that will hopefully help newcomers waste less time on some of the mistakes and technical challenges I had. Here are the visualizations of the results.

I want to thank Nexar for providing this great challenge and hope they organize more of these in the future! ?

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.