Beginning in 2016, China saw the sudden and meteoric rise of the short video social media platform Kuaishou 快手. The app had been quietly accumulating a following since its launch in 2011, focusing on half-organic, half-algorithm-driven growth and ignoring traditional media and influencer marketing altogether. The strategy worked, and as of 2018, it was sitting on a registered user base of over 700 million people, with 100 million daily active users.

What makes it unique among Chinese apps is not its feature set, but the demographics of its user pool, which is comprised of a higher percentage of rural and small-town residents than competing short video platforms. This emerging user segment has given rise to a new type of influencer, the tuwei 土味 KOL, one that doesn’t bother with the manicured, fashion-focused gloss — aka the chaowei 潮味 style — that characterizes urban internet celebs.

And the Chinese internet loves it. Giao Ge, a tuwei KOL whose main shitck is comedic sketches delivered in thick local dialect, has amassed 3.1 million fans.

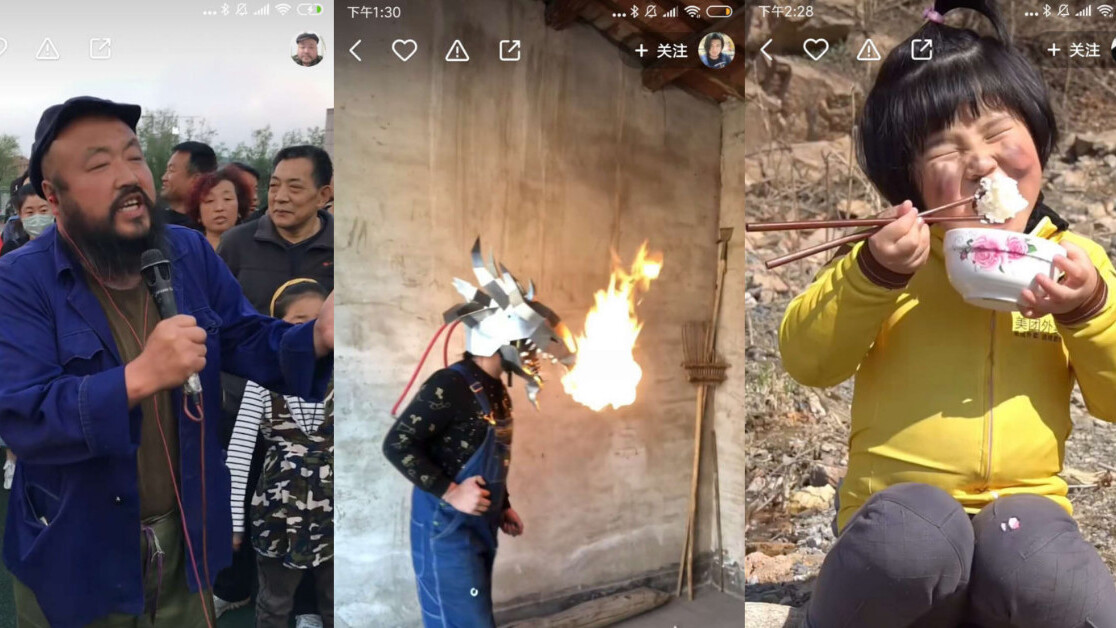

In Hebei province, Shougong Gengge 手工耿哥 made a name for himself through a mix of whimsy and ingenuity, attracting 3.2 million fans with a series of videos profiling his wacky inventions, like this dragon helmet that actually breathes fire:

And then there’s Jilin-based Dehuitabaoge 德惠他宝哥, a bearded, middle-aged singer in a pageboy cap whose 4.8 million fans visit his feed to watch him belt out folk songs in public parks. Need a little perspective? Kay. That’s more followers than Jack Dorsey, the guy who founded Twitter.

There are agricultural influencers that film their harvests, grandmothers who play musical cups on camera, and village kids doing drag comedy in their grandmother’s dresses, many with audiences over a million strong. All this falls under the tuwei banner. So what ties it all together?

What exactly constitutes “rural flavor”?

Other than place of origin, it’s hard to define precisely what makes tuwei content, well, tuwei.

In common usage, the term can be disparaging or complimentary, depending on its target. Used negatively, saying that someone is tuwei is the equivalent of calling them a redneck. It also refers to unsophisticated fashions or mannerisms that have fallen ludicrously out of date. Used positively, it’s a nod to the organic simplicity of the rustic farmland ideal.

The spectrum of tuwei influencers mirrors that dichotomy. On one end are celebs like Liziqi 李子柒, whose videos play out like meditation tapes, all rapeseed fields, bubbling brooks, and artful flower arrangements created beneath the shadows of the Sichuan mountains.

On the other end are endearing father-daughter team Gaoxiaofunvxugong 搞笑父女徐工, whose skits come across as the Chinese equivalent of Honey Boo Boo: he wears silly costumes while she stuffs her adorable face on camera — or, you know, plays with butchered pig heads. Typical stuff.

Author Zheng Zhuoran takes a stab at defining the essence of tuwei in his essay for online marketing blog Chuanbo Ticao 传播体操. In it, he lists what he sees as the four common threads running through the most popular rural channels:

Coarse realism

Happy-go-lucky chef Meishi Zuojia WangGang 美食作家王刚 made the Chinese internet simultaneously gag and applaud with his way-too-realistic recipe videos, featuring graphic depictions of the poultry-slaughtering process.

Many tuwei channels are equally unapologetic in their matter-of-factness, and feature non-sugar-coated looks at the less savory aspects of village living.

Use of rural dialects

This one’s a gimme: many rural KOLs speak in regional accents that mark them out as distinctly provincial.

Personal catchphrases and cliches

Zheng points out that a number of the bigger tuwei celebs have adopted personal slogans that come across like car-dealership jingles.

Lack of self-awareness

Zheng also observes that many rural KOLs display a real or pretended lack of awareness about their own “provincialness” — either through unabashed, exuberant self-confidence, or through deadpan delivery.

What’s the attraction for urban users?

Zheng’s piece credits tuwei‘s popularity to a few different factors, but he reckons it largely comes down to “pretty fatigue” — an inevitable public backlash against the carefully-manicured perfection of beauty-queen influencers. Beauty, says Zheng, has been edited and Photoshopped, and edited again, into something uniform and monolithic. This manicured approach gets tiresome, but there are endless ways to “appreciate ugliness”.

Interesting take, but we’d argue there’s more to it than that.

For urban consumers, the attractions of tuwei are myriad. Sure, it’s a little bit about poking fun at hillbillies and cringing at the mud-spattered reality of animal husbandry. But it’s also about yearning to get back to nature and the perception of the countryside as a place of purity, where the food is fresh and life is simple.

It’s also about retro nostalgia — many rural residents are still using electronics, home decor and clothes that urbanites haven’t seen since they were kids. The environments hearken back to simpler days, reminiscent of a China that has all but disappeared from metropolitan life.

And finally, it’s about admiring the romanticism and DIY-spirit of a rustic lifestyle. As urban culture becomes further removed from sources of production, there’s a certain fascination with the idea of self-sufficiency: slaughtering your own chickens, planting your own corn, and sewing your own clothes.

Maybe most practically, while urbanites might trust traditional influencers for skin cream recommendations, they visit rural KOL channels to make farm-to-table purchases, sidestepping supermarket chains whose claims of “free range” meat or “organic” produce are perceived to be suspect.

Where culture goes, marketers follow

The rising popularity of rural KOLs has pushed tuwei beyond the bounds of short video platforms and into pop culture, spurring an outpouring of tuwei emojis, memes, and predictably, marketing campaigns. Rural influencers have been invited onto major national talk and talent shows — Giao Ge recently appeared on the hit talent competition Rap of China — and businesses like Agricultural Bank of China have jumped on the bandwagon in recent months with a spate of well-received tuwei ads.

Why it matters

Kuaishou is a living record of China’s diversifying internet population and the “sinking market economy” — a terms that refers to the trickling down of consumption trends from first- and second-tier cities to third-tier cities and below.

It’s also a window into the lives of the users that will be driving the growth of China’s apps in coming years. By extension, tuwei isn’t so much a trend as it is a sign that China’s rural populations are becoming a strong and vocal presence on platforms that have underrepresented them for, well, ever.

Trivium User Behavior helps tech teams understand the human factors driving China‘s user markets. Our analysis sits at the cross-section of usability, sociology, and consumer research.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.