One consequence of Brexit is that Britain will desperately need a modernizing industrial strategy. In Boris Johnson’s mind, a key element of this is the recently announced “green industrial revolution” which included bringing forward to 2030 a ban on selling new petrol and diesel cars and a commitment to spend a further £1.3 billion on charging infrastructure for electric vehicles.

This announcement might suggest that the transition to more sustainable mobility is ambitious but straightforward. After all, we already know how to build a decent electric car and charging point technologies are also well established. So surely the green revolution is a simple matter of increasing the pace and scale of what is already here?

But this glosses over the complexities of such a radical transition. There is still a great degree of uncertainty involved in everything – from how many charge points will be needed and where, to how our practices and our streets might have changed by the time we reach the other side of the transition.

Electric and hybrid vehicles account for nearly 10% of sales but are still less than 1% of cars on British roads. Therefore, electric drivers are still the 1% of people whose circumstances make it easier for them to adapt their driving practices to the needs of the technology. They tend to be people who like novelty, are concerned for the environment, and who may not drive long distances. They also tend to be wealthier people with access to off-street parking who can easily install a charging point at home.

But if the ambitious goals of the green industrial revolution are to be met, technology must adapt to the needs of people from all walks of life. We cannot simply ban everyone from getting a petrol car, install a charging point in every neighborhood and think that will be sufficient. The government envisages most charging taking place at home, describing it as a “key attraction” of electric car ownership.

But many city homes do not have access to a drive or other off-street parking – in London, for example, two-thirds of households have no off-street parking. Would it be feasible to install on-street charging points next to all such houses? Even if it were, what would that do for street clutter? How would the pavements change if they became crisscrossed by electric wires?

After the UK government created an Office for Zero-Emission Vehicles (OZEV) ten years ago, one of the office’s first actions was to launch the Plugged in Places program, deploying charging points in a range of locations across the UK (we were involved in the Milton Keynes deployment). The program initially focused totally on the technology – but local authorities and industry partners were encouraged to take different approaches to charging to analyze the effectiveness of different strategies, locations , and charge point types. Some went for shopping areas, others workplaces – and a variety of charger designs were explored and ways to use them. Ever since, electric vehicle policy in the UK has had an important element of experimentation and learning by doing.

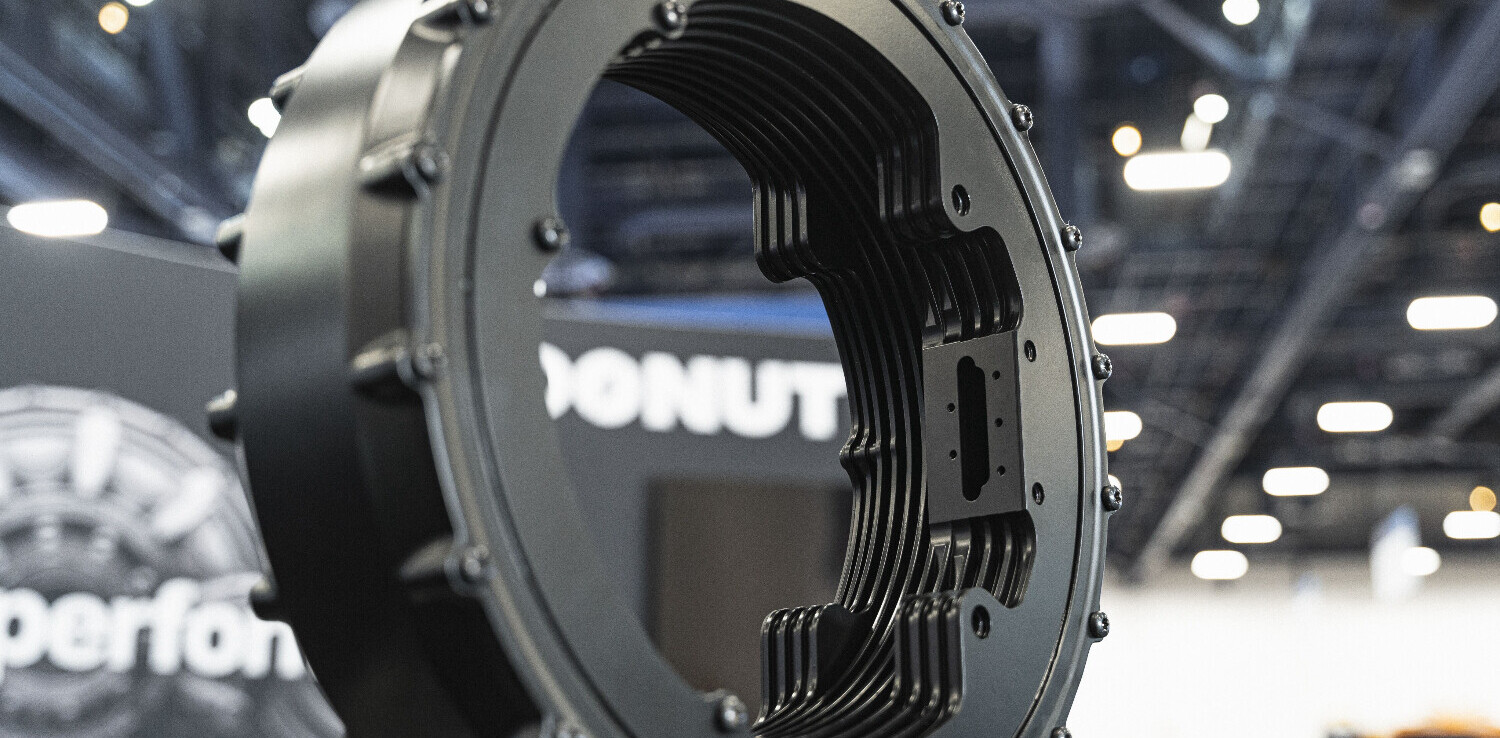

Today our team at the Open University is involved in another charge point trial, which is one of a number of government-funded projects exploring different approaches to providing electric charging in public spaces. Ours explores the possibility of wireless charging. Wired on-street residential charging looks fine now, but mass use could produce a tangle of cables which people could trip over, especially the elderly and poorly sighted. In the long term, some form of wireless systems will be needed and will have to be deployed in a variety of situations – on terraced streets, in neighborhood charging hubs, or even – were personal car ownership to fall – as part of a car club or as a new system of public transport.

This approach may or may not be suitable for achieving the goals of the green industrial revolution. The danger is that today’s needs in the still-emerging electric vehicle market might not be right for the mass market of the 2030s. Perhaps none of the current generations of trials will find an answer, or perhaps some may, or maybe some will lead to solutions that will work in particular contexts. What is important is that a clear vision for the future is complemented by a profound awareness of the uncertainties involved and a willingness to experiment and engage in acts of socio-technical imagination.![]()

This article by Miguel Valdez, Lecturer in Technology and Innovation Management, The Open University; Matthew Cook, Professor of Innovation, The Open University, and Stephen Potter, Professor of Transport Strategy, The Open University is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

SHIFT is brought to you by Polestar. It’s time to accelerate the shift to sustainable mobility. That is why Polestar combines electric driving with cutting-edge design and thrilling performance. Find out how.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.