Firstly, let us define what civic technology, or civic tech as it is sometimes known, is.

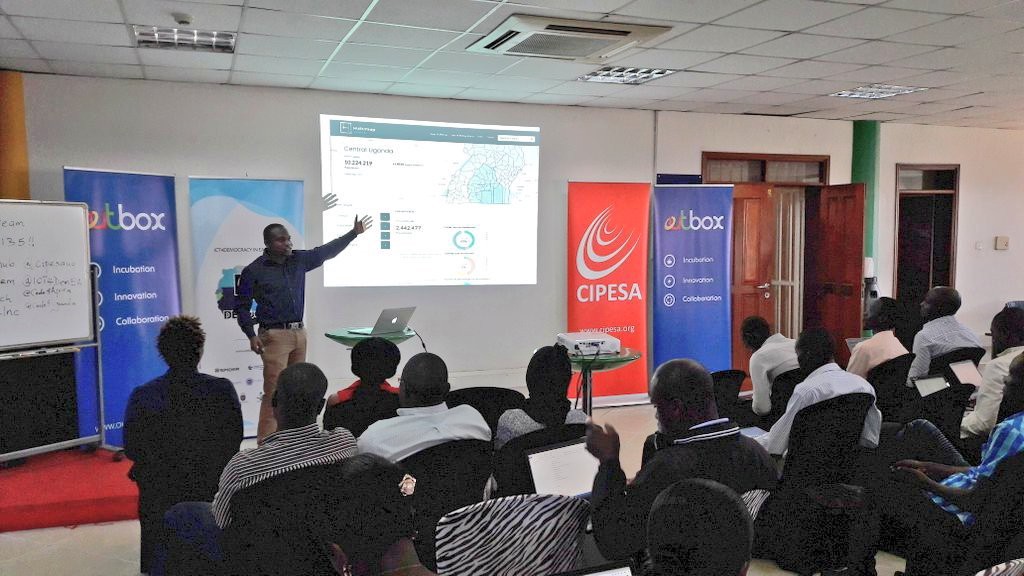

On 4 July 2017, the United States of America which is is also known as the founding home of civic tech, was popping confetti and fireworks in commemoration of her 241st year of independence. On the same day in Kampala, Uganda, there was a showcase of civic tech tools.

A full day’s event was hosted by technology and incubation space, Outbox, in conjunction with the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) to showcase civic tech as a tool of accountability in Uganda, and the Afrika at large.

A brief primer on civic tech

For many, civic tech is the bridge between a government’s mission and modern technology’s potential. However, we need to remember that civic tech has largely gained prominence only in the recent past, with the accelerated rise of the Internet and by extension social media, when savvy computer programmers, designers, civil servants and members of the private sector came together to create solutions to some of the most pressing problems stemming from ill governance of society.

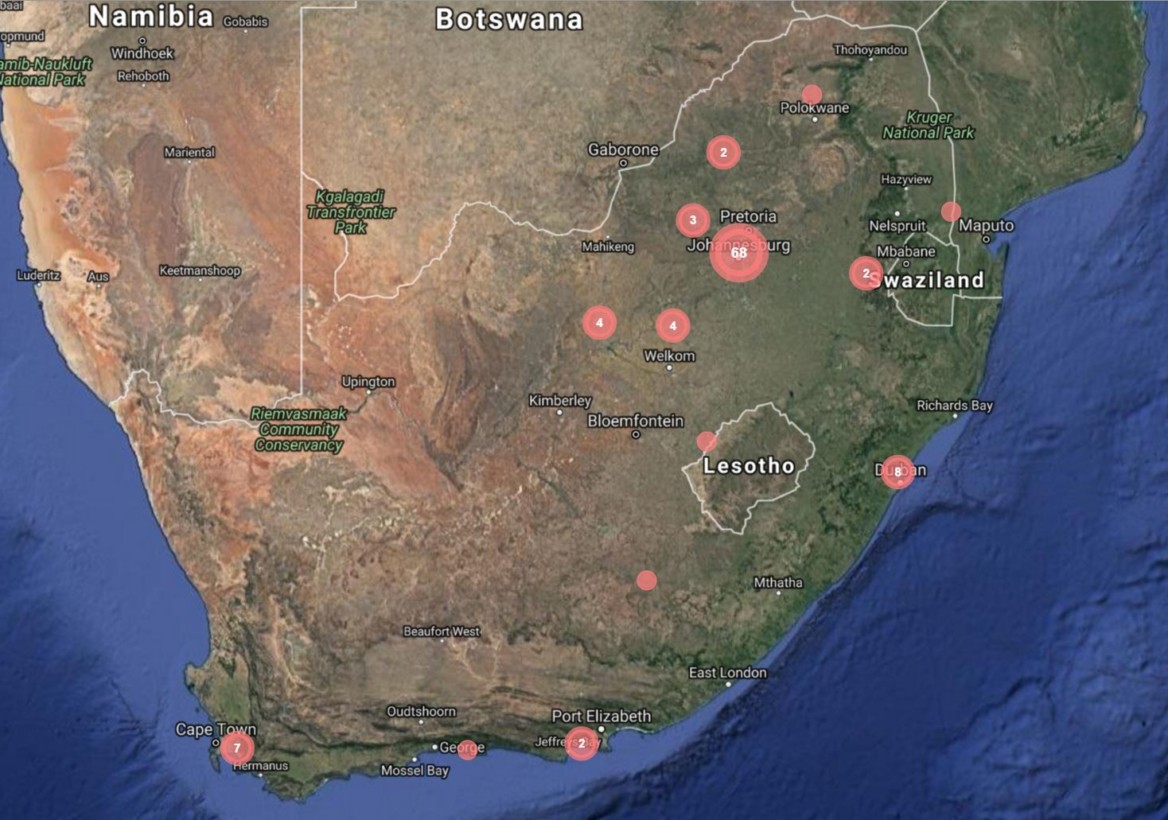

A remarkable example of civic tech in East Africa is Ushahidi. Ushahidi was developed in Kenya during the tumultuous 2007 post election period. At the time, there were episodes of violence as innocent and unsuspecting people were killed and attacked following the uprising after Kenya’s 2007 elections. To address this, the Ushahidi team deployed a relatively inexpensive and widely accessible SMS, social media and web platform to map the hotspots of violence in real-time. The interactive heat maps were used to inform Kenya’s citizens and the security forces of the fault lines supercharged by a volatile and incendiary electorate.

Arguably, no other tool has gained such global acclaim like the aforementioned. However that is no measure or sign whatsoever that civic tech is not appreciated — and used, in Uganda, and East Afrika at large.

Where is the edge?

In the age of the Internet and social media there has remarkably been an increase in civic conscientiousness and awareness.

According to recent figures from the Uganda Communications Commission, Uganda has just over 13 million Internet users; an estimated 32% of the total population. It is further estimated that the majority of those plugged into the Internet live in urban and peri urban areas.

With increased economic interests in urban areas coupled with increasingly young and tech savvy population seeking economic opportunities, there is even more pressure from the government to deliver. While it is widely renowned that public officials in Uganda have practiced spates of corruption, embezzlement and tepid responses to the citizenry in wake of calls for accountability; civic tech offers a possible solution to issues at large.

Civic tech deals in the business of information which has nefarious ties to it. Information such as public expenditure, crime statistics, development plans et al have some of that attached to them. When civic tech is leveraged as an intermediary between government and the citizen then there is more openness and accountability.

This feedback loop has a ripple effect in a way that government and other service providers religiously speak the language of service delivery without mincing words or cutting corners.

Getting to the main point

The day’s opening remarks were made by CIPESA Programmes Associate, Ashnah Kalemera who introduced CIPESA and most profoundly ICT For Democracy (#ICT4Dem), the programme through which the day’s event was organised — with an aim to promote human rights and democracy in East Afrika through ICT.

She further made remarks about what was expected and highlighted briefly what had taken place on 16 June 2017 at a similar showcase at Buni Hub, in Dar es salaam, Tanzania.

Outbox founder and Code4Africa lead in Uganda, Richard Zulu, took it away from there. A parade of civic tech products, tools and initiatives were highlighted in this lengthy presentation. Most remarkably was PesaCheck, a Kenyan founded fact checking tool for news and media whose arena has recently been proliferated by the unnerving rise of “fake news”. Still, in the post-truth age, there has never been any more dire need for fact checking of public budgets, procurement process, polling data, census data et al. Among tools presented included:

- Budeshi: an open contracting platform meant to strip away the opaque details behind public procurement.

- Siyanza: a platform to unmask contracts and bids awarded through lobbying by charlatan politicians.

- Citizen Reporter: a citizen journalism platform.

- HURU Map: a visualised data repository of Uganda census data.

- Dodgy Doctor: a content first platform by the Star Media Group in Kenya to identify and shame quack doctors.

- SADC Medicine: a web tool for proving authenticity of medicine in drug stores.

By the close of Richard’s presentation one couldn’t help but look on with wonder at how much a group of hackers and designers and lobbyists had collectively put across to promote civic engagement from different and several facets of governance.

Richard gave a great example of a case of citizen journalism where in 2016, an unknown citizen filmed a police patrol truck in what seemed like a deliberate knock of an enthused supporter during one of the unlawful but peaceful procession. What he didn’t mention was that the alleged driver who was arraigned in the courts of law was recently acquitted on the grounds of absence of “sufficient” evidence.

This example aptly summarises the hurdle behind the long walk to fully embracing civic tech in Uganda and East Afrika.

When does one gain the confidence that their query sent via the AskYourGov platform has been seen, or in some extreme cases, has bounced?

Furthermore, when does one gain the hope that their query will be replied to or, as in many cases, be flushed down a bottomless pit of silence?

As some researchers have found out, it is very paramount to get an acknowledgement of receipt for any sort communication made to government officials. Even with electronically signed emails and other diplomatic cables, the proof of receipt can easily be swept under the rug.

Isaac Latigo from Parliament Watch Uganda — a collective of social media savvy journalists and activists — presented a catchy slideshow of their works. They guid3 aging legislators to new and modern platforms of communication. While the youth are increasingly adopting social media and civic tech tools, across the divide, the August House mainly dominated by aging legislators and public officials is not and this despite the legal and regulatory frameworks that demand of MDAs to publish and provide information on demand.

The strategy behind Parliament Watch’s activities is in the duality of execution. In one way, they rally MPs to adopt social media and diligent use of e-mail and other digital forms of communication. In some cases they even open up these digital accounts for the aforesaid officials.

Now, on the other hand, they must create engaging content for their target consumers — the citizens.

Since they are in the business of reporting on the long and boring parliamentary proceedings, they must commodify these proceedings in short and terse and catchy segments. The biggest upside is in some isolated incidences, like the #MPsEngage segment on Twitter they have garnered more mileage than what could have been possible for the same, on mainstream media.

Not enough

When requests for data are made to MDAs and go unanswered, or if lucky enough, rejected (not discounting that a few requests are granted), then that undermines the laws and charters the country subscribes to; access to information, right to information, universal declaration on human rights, among others.

This is not reason enough to throw in the towel. Fair enough, there is still interest from the government’s side. If they are truly engaged, at least, ParliamentWatch showed us that it is possible albeit on a small scale.

A duo comprising of Daniel and Ivan from Omuliisa co-presented their flagship product; M-Omuliisa. It was initially developed to provide agricultural extension services to rural farmers in Uganda but has since been refashioned to serve the growing needs of service delivery.

M-Omuliisa is deployed in the Northern and Eastern parts of Uganda through available via SMS and web platforms. The team couldn’t emphasize enough how the product was made possible through intimate and prolonged engagements with stakeholders right from the parish and district levels. Feedback from the initial product development phases were incorporated and concerns affecting the product were addressed almost immediately.

However, the narrative about the proliferation of mobile devices in rural areas is probably oversold according to revelations from Daniel, one of the presenters. While potential for change was huge, and the trails by the disruption of mobile money were significant, the challenges surrounding literacy of the rural populace could possibly be the largest impediment to adoption of basic technology (as an intermediary to service delivery).

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic — Arthur C. Clarke

He said, they had to teach the rural farmers intuitive and basic tasks such as sending texts and interpreting feedback from USSD platforms. A prohibitively expensive and mundane process, quite often technology solutions did not cater for.

According to 2014 census data, about 75% of Ugandan live in rural areas. This is a significant number that must be included in the civic tech agenda at all costs. This is what inclusive is truly made of.

The panel of the day comprised of Gerald Businge of Ultimate Media Consults, Lillian Nalwoga of CIPESA, Ray Besiga; a designer and software developer at Sparkplug and Joshua Akandwanaho from NITA-UG. It was moderated by Brian Lamtoo, a software developer with Creative DNA, the makers of NTV Go; a citizen journalism mobile application in Uganda.

Ray introduced Urb, a mobile application he developed to crowdsource reports on shortcomings of services rendered by government and her parastatals such broken utilities, potholes, and the like affecting city dwellers. With great pleasure, he announced that one pothole had been refilled thanks to that one of the handful reports submitted on the app. In line with the power of crowdsourcing, Yogera.ug, was developed by a team at Hivecolab (the first tech hub in Uganda). It seeks to promote “whistle-blowing” of the bad, and celebration of the good, among civil servants through crowdsourced responses from the public.

KCCA, in the last couple of years, has taken significant interest in creating a city that works for the inhabitants. Similarly, it has proactively adopted civic tech platforms such as social media and other platforms such as its own mobile application and parallel web portals. For example, during the event, two platforms were showcased. User.ug is a web platform for monitoring clean construction projects in the city. The other was a solid management system, to monitor volume and distribution of waste management service providers.

Moving on, Joshua Akandwanaho on behalf NITA-UG highlighted the importance of government investments in enabling civic tech. He reemphasized what Mr Moses Ocero, the Assistant Commissioner at Ministry of ICT & National Guidance, had earlier talked about. In the current financial year, the government had dedicated about UGX 248.15 billion, an estimated 0.86% of the national budget to the Ministries of Science, Technology and Innovation and that of ICT & National Guidance and supporting agencies. This by any measure may look like a drop in the ocean, however it is a significant increase to the ICT sector that was barely allocated to about USD 2.5 million in FY 2014/2015 (back there Ministry of ICT represented almost the entire ICT sector) to the current USD 68 million.

Also, with the growing interest in Public Private Partnerships (PPP) and private sector involvement in ICT infrastructure projects such as the USD 12 million Facebook-Airtel Uganda-BCS partnership fibre optic project in West Nile Uganda, there is much potential.

Moreover, the government is deeply interested in developing and supporting ICT infrastructure such as her own national fibre optic backbone; in order to link all MDAs to a centralised and accessible network. In the evenings, and as already piloted in the metropolis of Kampala, free wi-fi from the freed bandwidth is availed to citizens at no charge.

Through implementation of existing laws such as the Access to Information Act, and the proposed Open Data Policy, more is expected from government in trading information between her MDAs and the general public in different and more engaging ways.

These synergies in government, Gerald Businge called should be even more nuanced in the media fraternity. He said that they as a fraternity ought to adopt development of tools and products in partnership with software developers and designers.

It was at this point that Lillian Nalwoga called for concerted efforts in different facets of the stakeholder engagement. She decried that for long many CSOs have been working in closed silos insulated from the software development community. What better way was to approach civic tech was people from diverse backgrounds and collectively prod and prod until there was more spread and adoption of tools to promote accountability and transparency.

At the end of the day, one money quote rang true, “Civic tech is not about the exploitation of technology but service to community.”

This service is paved neither by only bits and bytes, nor even just good intentions, nor ideological hairsplitting, but by deliberate action and concerted efforts from a range of responsible stakeholders. The civic tech showcase was just the beginning of many showcases to come.

This post was originally published by iAfrikan. Check out their excellent coverage and follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.