There’s certainly something in the air at Silicon Roundabout, and I’m not talking about car exhaust fumes.

David Cameron’s vision for East London’s transformation into a hot-spot for tech startups seems to be well on course, but let’s not give too much credit to the Government. The cluster of companies that call Shoreditch home was growing long before the UK Prime Minister announced his plans for Tech City, with organizations like TechHub boosting London’s burgeoning startup scene for over a year now.

It seems you can’t go a day without reading something about Silicon Roundabout. Whether it’s a million-pound funding boost, a new ambassador for New York, or the news that a major San Francisco-based social network has set-up shop at TechHub. (Sorry to disappoint you, it’s not Facebook.)

The scene’s buzzing. A little too buzzing, some might say, and surely this level of excitement hasn’t been seen since, oh, I don’t know, 1999?

Can it even be called a dotcom boom? The surge in wacky international domain names should mean that it’s called a dot-ly, dot-is or dot-it boom. But that’s just word games. The dotcom boom is real, and whether you’re in Silicon Roundabout or Silicon Valley, everyone’s asking the same question: Is it a bubble, and is it going to burst?

There’s no easy answer to that much-mooted question, but to get a sense of where we’re at just now, it may help if we look back a decade or so to see what things were like then. Are there any patterns we can spot? Is there anything startups and entrepreneurs can do to dodge the shrapnel should the dotcom market crash for a second time? What is the difference between then and now?

To help me find an answer, I spoke with Rupert Cook, Head of Technology (Mergers & Acquisitions) at Goetzpartners, and an investor, adviser and entrepreneur. Cook’s also the author of Selling Your Technology Company for Maximum Value.

Here’s what Rupert had to say…

In the beginning…

“In mid-98 I gave up my job at a consultancy, because it was obvious something very exciting was happening elsewhere”, says Cook. “Me and a number of others at the company had pitched various Internet-related ideas to the guys at the top, but they weren’t sold on the whole Internet thing.”

It seems that the big old-fashioned companies just didn’t get it. So Rupert, and many others like him, jumped head-first into that ‘fad’ called the Internet. Cook continues, “Lots of people were quitting their jobs. They had sensible jobs in consultancies, banks, insurance…but that’s how the UK dotcom boom started.”

A new country

With the benefit of hindsight, they seemed like very innocent times. New Labour, led by the dynamic and charismatic Tony Blair, was creating a buzz; Britpop was still a recent phenomenon; everybody was talking about this thing called  Cool Britannia; and a new millennium was on the horizon. The late 20th century was an exciting time to live in the UK.

Cool Britannia; and a new millennium was on the horizon. The late 20th century was an exciting time to live in the UK.

Then there was this thing called the Internet. A whole new media that people were embracing and dismissing in equal numbers, but those who saw its potential were eager not to be left behind.

“There was this fever, I think it was tied-in with the upcoming new millennium”, says Cook. “The feeling was that the Internet was much more than a whole new media, it meant a whole new economy. The feeling was everything was going to be different and there was a great deal of optimism. Unlike now, where we’ve just come out of one of the worst recessions ever.”

So, in the UK at least, the dotcom bubble was only part of the story. It felt like a whole new country was being born, and those with the minds and the money to get involved did their very best to do just that, otherwise they’d miss. Cook continues: “There was a feeling that everything had changed and people were being empowered. That helped a lot. People thought ‘I’ve got to be part of this, if I’m not I’ll just watch this go by’.”

Playing catch-up

Silicon Valley is where it all started though, about two years before this ‘fever’ hit UK shores. It seems that people felt a need to catch up, and the first forays into Internet businesses felt like a giant land-grab, a modern-day gold rush. People didn’t really know what the Internet was, but they felt they needed to be part of it.

“Because it was all new, there was a feeling that experience didn’t count for anything, because nobody had any”, says Cook. “There was a feeling that anyone could do it. The rulebook was being written from scratch, therefore there was no barrier to entry.”

It was this initial “I know as much as anyone else about this” attitude which led to the first real surge of Web companies in the UK. And it wasn’t about revenue, not directly, at least.

“The idea of making revenue wasn’t at all important”, says Cook “It was all about getting users. The feeling was that companies would be valued on their number of users, and they would be able to raise a lot of money if they’ve got lots of users. Then maybe they’ll be able to float the company.”

One of the best examples of this was Freeserve, a UK Internet Service Provider (ISP), founded in 1998. Freeserve ![]() started as a project between Dixons Group plc and Leeds-based Planet Online. The idea was that free Internet access would be provided to customers buying PCs from Dixons’ retail outlets.

started as a project between Dixons Group plc and Leeds-based Planet Online. The idea was that free Internet access would be provided to customers buying PCs from Dixons’ retail outlets.

“Freeserve did have revenues too”, says Cook, “but its valuation when it floated was pretty much a correlation of the number of users it had. Multiply your users by a number of dollars, and that’s how much you’re worth.”

Cook also noted that Freeserve tried to buy one of his ventures at the time, an online company called Web Weddings, a successful dotcom service (in terms of users) that organized weddings. But why would an ISP try to buy an online business specializing in marital affairs? Cook explains:

“They wanted content. In those days, the idea was, if you could get people using your ISP, the longer you could keep them in your own properties, the better it was. It was the same when AOL and Time-Warner merged – everybody was trying to create these great walled-gardens, where there was loads of content so that you would never have to go anywhere else.”

As crazy as it may sound now, Freeserve offered Cook’s team £5m for Web Weddings, but they turned it down because they thought it should be worth £50m. Why? Because of their number of users – of which there were tens of thousands. This was a mere six months after they’d started the company with £60k in capital. What about hindsight? “I should’ve taken the money and run”, says Cook.

But Cook had set-up an incubator and was launching many dotcom companies, from which Web Weddings was only one.

“We had people pitching to us all the time for investment”, says Cook. “And their own valuations were just totally crazy, all based on their projected number of users. So they didn’t even have the users in place yet.”

This was a familiar story elsewhere too. Silicon Valley spawned countless crazy valuations based on little more than ideas scrawled on napkins. But there was one key difference between the dotcom boom in the UK and its Californian counterpart.

“There was this feeling that we had to catch up with the Americans”, says Cook. “America seemed to be taking over the world with the dotcom stuff, and the feeling in the UK was not so much about copying what was going on in the US, but making up for lost time.”

The 2-year lag between Silicon Valley ‘getting it’ and the UK latching on meant that there was a real sense of urgency. But underneath all that, Cook suspects most people recognized that the excitement was going to be short-lived. “I think deep down people realized it was a bubble. There was a bit of a frenzy then, something that isn’t there with the dotcom boom today”, says Cook.

The First Tuesday phenomenon

The First Tuesday phenomenon kicked-off in London in 1998, started by Julie Meyer, an American-born entrepreneur. She was a relatively junior person at NewMedia Investors (now Spark Ventures) which was an incubator that advised companies such as Lastminute.com, one of the big success stories to emerge from the first UK dotcom boom.

In October 1998, alongside Nick Denton, John Browning (both journalists) and investment banker Adam Gold, Meyer began organizing networking events for tech entrepreneurs on the first Tuesday of each month. This became known as ‘First Tuesday’ and eventually spread into many major cities across Europe.

From the first meeting in a pub, with just a few people, the First Tuesday phenomenon exploded. “I remember going to one of the biggest ones in Lord’s cricket ground”, says Cook. “There were 1,500 people there. Another one I went to was held in Fabric nightclub. It just got bigger, and bigger, and bigger.”

The point of these meetings was to connect startups, who wore green dots, with investors, who wore red dots. So essentially, these drink-fueled parties were a stream of green dots chasing a crowd of red dots, who were all trying to avoid the people wearing yellow dots – the advisers, accountants, lawyers, bankers etc.

First Tuesday is still going today, though in a slightly different guise. “It’s a shadow of its former self”, says Cook. Check the promo video out for yourself:

http://youtu.be/DJpGIgQeXSg

Music Unsigned

It was at the First Tuesday part at Lords where Rupert Cook was introduced to one of his other ventures from the first dotcom era, a company called Music Unsigned. Not only did Cook meet the company founders at this event, he also hooked up with a guy who would later put a lot of money into Music Unsigned.

“After working closely with the guys from Music Unsigned, I rang up the investor I’d met at the event and told him we had a business plan”, said Cook. “And he put £250,000 into the company, without any paperwork.”

It was this kind of outcome that First Tuesday had the potential to produce. But it was also indicative of the sense of excitement people were feeling at the time – people were putting up a lot of money with very few formalities in place. This was true in Silicon Valley too.

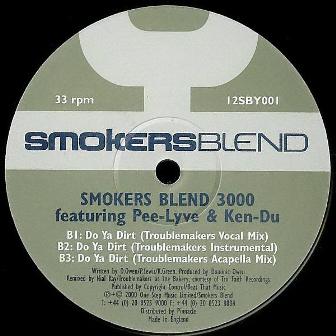

“The first band on Music Unsigned got their recording contract over the Internet”, says Cook. “They were on the front cover of NME and other music magazines and secured amazing PR on the back of how they were signed.”

The band in question was Smokers Blend 3,000. They were signed on the basis of the music they uploaded to the Music Unsigned website. Whilst the band didn’t go on to fame and fortune, another band did five years later, using a similar approach to Smokers Blend 3,000.

Arctic Monkeys are generally considered as one of the first acts to gain worldwide success through the Internet, and the band gained a big fan-base and subsequent record deal based on its presence on MySpace. This was a landmark moment which many argue heralded the start of a new era in music. And trailblazers such as Music Unsigned helped pave the way for future successes elsewhere.

Music Unsigned ended up floating in October 2000, 6 months after the dotcom bubble had burst. So there was a lot of money in the company, but given the precarious predicament the whole Internet scene was facing, the shareholders decided it was best to have the money tied up in a safe, profitable company. Thus, an insurance company swallowed Music Unsigned and that was that.

“It was a great shame”, says Cook. “It was a great success for quite a while but it was perhaps a little bit ahead of its time.”

And this was the story for many startups, both in the UK and in Silicon Valley. Working out a proper business model for an unproven idea, combined with a lack of widespread fast Internet, meant that many great ideas simply died.

The money factor

One of the key differences in the first dotcom era, was the ease with which companies could raise capital, as we saw with Music Unsigned.

“The fundraising was so easy back then”, says Cook. “Today, there are many more experienced investors in the space who don’t throw money about.”

The investors back then were essentially taking a lot of risks on unproven ideas, ploughing money into ventures that were, in hindsight, always doomed to fail. There were many inexperienced entrepreneurs who had nothing to lose should their business fail, because the investors were taking all the risks.

Today, investors tend to look for those with a proven track record in startups – repeat entrepreneurs, or businesses that have shown they can work based on similar companies in a particular space. That can only be a healthy thing.

Laying the foundation

It’s easy to view the first dotcom bubble as a failure, but it wasn’t. It laid the foundation for what we see today. It was a testbed – entrepreneurs, investors, advisers, bankers…everyone, all learned a lot from the whole episode and we’re a lot stronger for it today.

“The whole landscape has now been mapped out in terms of what can make money online”, says Cook. “There are still lots of new things being developed, of course, but at least there is now a basic model for what works online and what people are prepared to pay for.”

Back in 1998/1999, nobody really knew what people were willing to engage with online. Did people want to gamble, watch videos, listen to music, play games and chat to friends? We now know that they do, but it’s been a very iterative process to arrive at that conclusion, and the fall-guys from a decade ago were instrumental in the birth of the dotcom boom we see today.

Is it really different today?

Is it really all that different today? There are many examples of crazy valuations and large sums of cash being turned down by startups. Just look at Groupon, who reportedly turned down a $6bn takeover from Google last December. And when it announced that it planned to float back in June, a somewhat ambitious figure of $20bn was attached to the company, despite it not making a profit. In fact, it actually had a $450m loss last year.

The same applies to many other dotcom companies today, ones that have a lot of users, valued at crazy levels despite lacking profitability. There are echoes of ten years ago for sure, but a key difference is many of the companies are generating significant revenue, so the idea is that profits will follow. Whether that actually happens remains to be seen in many cases.

In the intermittent years between the two dotcom booms, technologies, attitudes, skill levels…everything, has caught up. And the latent potential the Internet always promised is now being realized. So even if all the Groupon-type companies fell tomorrow, the bubble would probably still remain in tact.

Ten years ago, dawdling dial-up prevailed and the cohesive gel we now know as social media wasn’t in place. This is a massive plus for the current dotcom boom and is why it’s not likely to go the same way as before – the infrastructure is now in place.

App-etite for success

Many startups these days are essentially an app, or a number of apps. And this should also be healthy for the tech scene in the UK and elsewhere.

“Nowadays to make an app, it’s so cheap”, says Cook. “It’s so easy to start an Internet company if you have just one game, one idea or whatever, and get that distributed. In fact, it can almost be free – if you can get a programmer mate to bring your idea to life over a single weekend, then you’ve got a business.”

And this is a key point. Startups can hedge their bets, develop 20 or 30 apps on the basis that at least one will be successful. Just look at Rovio, the Finnish developers that make Angry Birds. Rovio created something like 40 games before Angry Birds took the world by storm.

With apps, good ideas can be born without a massive commitment from those at the helm. They can be created in an entrepreneur’s spare time, developed and honed in the evenings and weekends.

In many ways, the current startup scene can be analogized with the music industry. In the same way as the Internet has made singles the main focal point of a band’s success rather than albums, individual apps can make or break a tech startup, and the need for an overarching supreme business model isn’t quite as important, certainly not in the very early days. And this could be good – it makes companies more lightweight and agile in their formative years.

Right…so is this a bubble?

“I don’t think this is a bubble like the first one”, says Cook. “I think this is an open evaluation in certain areas. This isn’t a complete hype bubble, as was the case before. There’s foundation in this one, and there’s serious money being made because it’s so much more easier to sell things over the Internet.”

“I don’t think this is a bubble like the first one”, says Cook. “I think this is an open evaluation in certain areas. This isn’t a complete hype bubble, as was the case before. There’s foundation in this one, and there’s serious money being made because it’s so much more easier to sell things over the Internet.”

And this is such an important differentiator between the the two dotcom booms. Most people would now agree that the Internet isn’t a fad. It’s real, everyone’s on it and smartphones make it ubiquitous. For that reason alone, there is a lot of money to be made online.

This is applicable across the board – in the UK, the US, Europe and in all the developing economies. Where there’s fast, reliable Internet, dollars, pounds, rupees and yen will flow.

As we’re seeing in the UK, there are proper clusters developing which is healthy for any startup scene. There’s Silicon Roundabout as we’ve already mentioned, and Cambridge too is emerging as a thriving hub for innovation.

“The clustering is really helpful”, says Cook. “There wasn’t really a similar thing going on before in the UK. There were a few companies around Brick Lane, but there wasn’t the same support network that there is today. There’s a lot of mentoring going on today too, entrepreneurs that have been there and done it. There are a lot of dedicated mentor programmes. I’m one of the mentors on the Springboard programme. There’s a lot of people offering their time for free to help new startups.”

There’s also a number of funds around now that have been developed by entrepreneurs who were around during the first dotcom boom, such as Profounders and Atomico, as well as government-led initiatives. The UK tech scene has the money and the minds to support it, and it’s definitely a lot healthier this time.

Spotify already calls London home. Twitter is looking to launch its first office in the UK capital too. Smaller startups such as Flubit and Use it or Lose it are just starting out on their journey into the unknown, and only time will tell if they succeed.

As for Rupert Cook, he’s still heavily involved in startups, with the likes of 360Amigo and Minimonos currently under his auspices.

There’s a lot going on across the UK, and whilst there may not be the same buzz as before, that’s perhaps because there’s less hype, and with less hype that might mean that this time around it’s for real.

Of course, many tech startups will crumble, that’s a given. But that has always been the case in every industry since the beginning of time. As long as Capitalism remains the dominant economic system, and the Internet isn’t a fad, then this ‘bubble’ won’t burst. It might shrink, it may expand and it will definitely evolve. But it’s here to stay.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.