The center of the Milky Way twinkles in microwave radiation, seen in new data obtained by astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. This study could help explain the behavior of supermassive black holes found throughout the Cosmos.

Supermassive black holes reside in the central core of every major galaxy. The one at the center of our own galaxy is called Sagittarius (Sgr) A* (usually pronounced SAJ a star).

Sagittarius A* has the mass of four million suns. Astronomers have seen flaring of radiation from this supermassive black hole before, but never in the detail recorded in this new study.

Hot spot, bright wavelengths

Thick clouds of gas and dust, obscuring the view of Sgr A* from Earth in visible wavelengths. However, it is possible to see through this material using instruments designed to detect radio and microwave emissions.

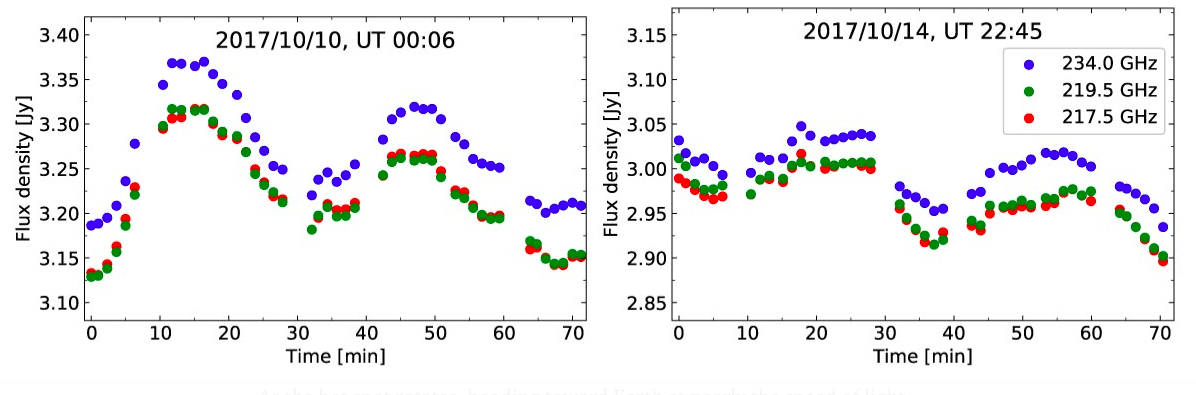

A team of astronomers examining the core for electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths of around one millimeter discovered a semi-repeating signal of microwave radiation. Astronomers knew that Sgr A* occasionally flares up at the wavelengths observed in the study, but the reason for the display was uncertain.

The ALMA team studied Sgr A* for 70 minutes a day, over 10 days. They found one wave of radiation amplifying and dimming over the course of an hour, and another which cycled in half that time.

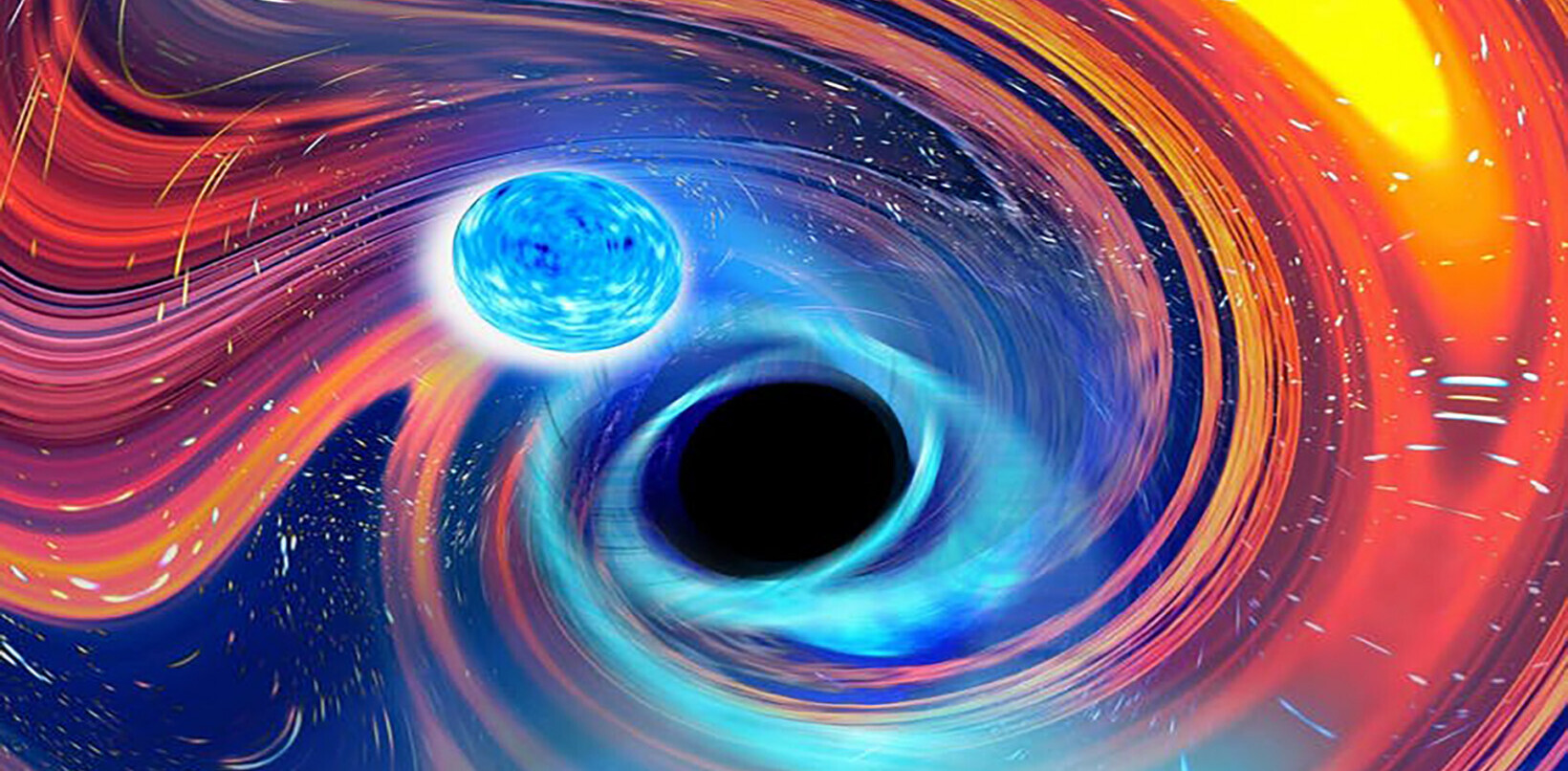

Researchers on the discovery believe the energy may be the result of a pair of bright radio spots orbiting close to the supermassive black hole.

Such hot spots would circle exceedingly close to the black hole, where gravity and radiation have extreme effects. A body with an orbital period of 30 minutes would orbit just 0.2 astronomical units from this behemoth black hole. This is one-fifth the distance between the Earth and Sun, and half the distance Mercury orbits from our parent star.

“This emission could be related with some exotic phenomena occurring at the very vicinity of the supermassive black hole,” suggests Tomoharu Oka of Keio University.

One theory to explain these features suggests that hot spots may occasionally form in the disk, emitting signals in microwave wavelengths. As the hot spot rotates, heading toward Earth at nearly the speed of light, relativistic effects amplify the signal.

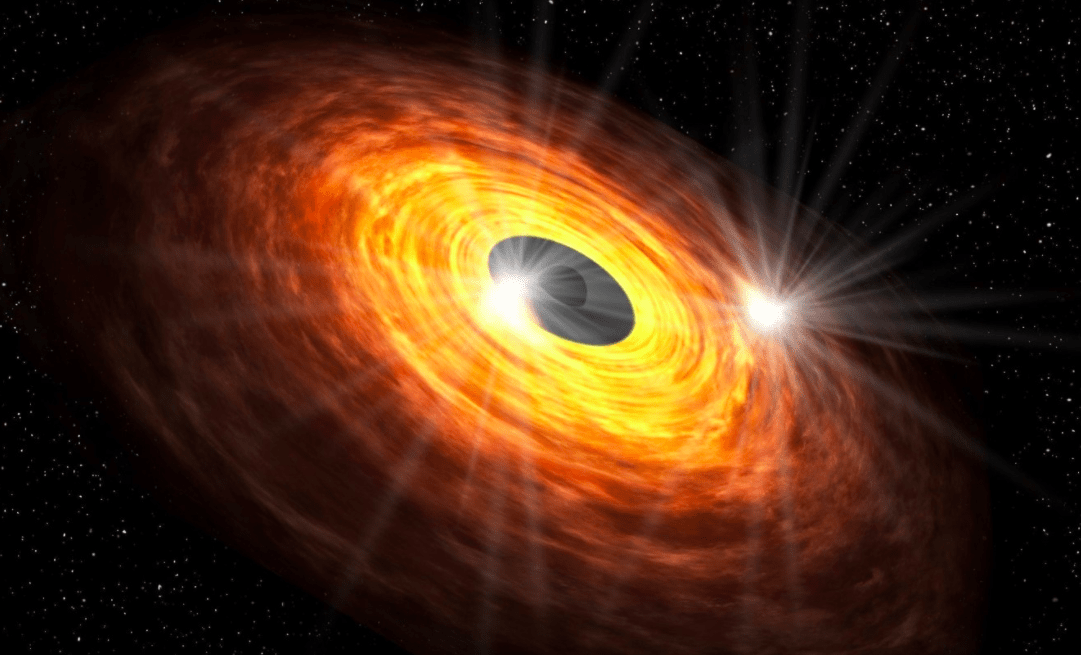

The world was recently awed by the release of the first-ever picture taken of the region surrounding a black hole in the galaxy M87. It is very likely the second image of a black hole will be our own supermassive black hole, Sgr A*. The NASA video below provides a look at the first black hole for which there exists a detailed image, the supermasssive black hole near the core of the galaxy M87.

Hot spots like those suggested in this study, moving at relativistic speeds, could make imaging Sgr A* more difficult, even with the Event Horizon Telescope.

Black holes do not produce any light or radiation (hence the name), but they are surrounded by matter that glows with electromagnetic radiation as it spirals toward the enigmatic object.

Orbiting so close to Sgr A*, these objects would be subject to vast gravitational forces. This could allow astronomers to study the effects on space and time of extreme gravity, researchers conclude.

The newest hot spots in the galaxy have a certain twinkle about them.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.