I get up every day, put on my jeans and walk to the kitchen to get breakfast. Already, I’m being tracked by my Fitbit One, which is logging every step I take, every staircase I climb and every mile I walk.

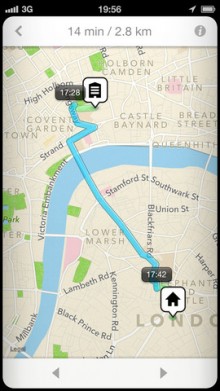

In the kitchen, I realise that I’m out of milk so I walk 500 steps to the local shop. Now not only is Fitbit tracking me, but Google is too, thanks to Latitude running on my phone, collecting a log of every single place that I go. It’s not alone. Moves, an app that is a hybrid of an activity and location logger, recognises that I took 500 steps to the shop and adds the data to its summary of my day. Then at the end of the day I stand on a Withings scale which immediately sends my weight to my Fitbit account.

Slowly but surely I’m amassing a vast amount of data about where I go and how much physical exercise I get. As something of a data geek, I love to look back at the graphs and maps I accumulate – but how exactly do they all help me? In fact, how much are any of us really helped by the data that ‘quantified self’ devices and services collect about us?

It’s one thing to know that you don’t walk enough or that you hit your activity goal for the day, but shouldn’t this highly personal data offer a little more in the way of practical benefit? Where is the ‘Quantified Self’ movement going?

He’s got the Moves

Sampo Karjalainen is the CEO at Protogeo, the Finnish startup behind the Moves app that has drawn acclaim on iOS and is due to arrive on Android this summer. In addition to walking, it can track cycling and travel by motorised vehicles. He believes that we’re only at the start of a long journey when it comes to genuinely useful ‘quantified self’ data.

“The first, and very significant, step is just to make physical activity visible,” Karjalainen says. “By making it visible it becomes a topic people start to think about.”

Indeed, Karjalainen says that he’s heard stories about users parking their cars a little bit further away from their destination in order to clock up more steps, skipping the bus to walk further and taking stairs instead of elevators.

“Building good feedback loops and motivating people to reach their goals is something we’ll start to work on soon. However, we think building intrinsic motivation is the key – if you over-gamify it with extrinsic motivators, you may get great results for some days or weeks, but even the best game becomes boring after some time.”

As Moves grows as a product, Karjalainen says that the key to success will be making the data capture process fade away from your awareness and simply allow the app to give you useful information without you really noticing that it’s been collected in the first place.

“The big change is that we can collect new types of data fully automatically,” he says.

“From the phone it’s possible to effortlessly track activities, places, communication, media consumption and creation, etc. You just carry and use your phone normally, but it’s collecting interesting data for you. Instead of just showing all that data back to you, we see that our job is to develop algorithms that find the interesting insights and provide those in a very clear and concise format back to you. That’s when Quantified Self can go mainstream.”

The quantified body

It’s certainly easy to see how factors like movement can be tracked in increasingly useful ways as products like Moves and the Nike FuelBand develop further, but how about further down the line? What else about your ‘self’ can be ‘quantified’, and how?

Consider food. Anyone who’s tried one of the nutrition tracking services already available (ranging from Fitbit’s food diary feature to apps like Nutrino, which launched at The Next Web Conference Europe 2013) will know that logging your intake is far from accurate. Unless you’re willing to weigh the portion size of everything you eat, and the service you’re using has everything that you eat in its database, all you’re going to get is a very rough estimate of your actual intake. That’s not so much ‘Quantified Self’ as ‘Guesstimated Self’.

Alcohol is another practical example. We all know that doctors set guidelines about safe drinking levels but how do you know when your body has consumed too much? When’s the tipping point that means you really should stop? Imagine if an app could flash up a warning as your body started to process that one unit of alcohol too many. You’d have no excuse for that hangover the next morning.

In your stomach or under your skin?

Imagine if you could track the inner workings of your body accurately. Imagine if your smartphone, smart watch, Google Glass-style head-up display or whatever you use could tell you in real-time when you’ve reached your daily recommended calorie intake, when you really should drink some water to keep at optimum hydration, or when you have a particular need for some, say, iron in your diet.

Implanted and ingestible technologies may provide the answer, although we have to wait some time before they are available for consumer-focused Quantified Self applications. Much of the work done so far has been in the healthcare and pro-athlete markets.

Take for example the CorTemp ingestible core body thermometer, which transmits your core body temperature to an RF-enabled device. It’s intended to be used to diagnose heat-related illness or to help athletes understand how their temperature affects their performance and vice-versa.

Proteus Digital Health is another interesting company in this field. The firm is developing a 1mm, safe-to-swallow sensor that communicates with a patch that you wear on your skin.

Venture-backed Proteus recently announced a partnership with Oracle to run clinical trails of the technology. At the moment, potential consumer uses for the technology include measuring heart rate, steps taken, sleep and rest. These all seem very similar to products that are currently available, but the company says that future uses will include care for people who have suffered heart failure, conditions related to the central nervous system and support for people who have had organ transplants.

Meanwhile, implants placed under the skin offer another way of collecting data about your health and activity. These could be used for everything from tracking vital signs and monitoring organ health to recording the growth of a tumour.

It’s very early days for implanted and ingestible technologies, and healthcare markets are likely to be the first stop for them as they emerge as commercial products. So, don’t expect to swallowing Nike+ pills and injecting a Fitbit under your skin any time soon, but when the day comes, the amount of data you’ll be able to collect about yourself is likely to skyrocket.

The other side of the coin is that your quantified self data is likely to become very useful to the same insurers who currently offer discounts to drivers who install tracking devices on their cars. “Pay a lower premium on your health insurance if you let us monitor your body,” is a likely scenario in the future. As for your employer, the traditional medical examination that some jobs require could be replaced by a mandatory look at your personal biometric data log.

Depending on where you sit on the privacy spectrum, this could be a creepy future that you want nothing to do with or a fairer, more data-driven society. As long as I know who access to my data, and I have access to all of it at all times, I say bring it on.

Image credit: AFP/Getty Images

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.