I just got back from a press trip to Bucharest, Romania. While there, I was afforded the chance to speak with Bitdefender’s CEO and founder, Florin Talpeş. We talked about the burgeoning Romanian tech scene, which was once dominated by outsourcing companies, but is now filled with genuinely innovative companies that are aggressively expanding abroad.

During our chat, Mr. Talpeş dropped a bombshell: in Romania, programmers (and other research and development professionals) don’t pay income tax.

I’m serious, and it’s not a swindle. Rather, it’s strategically clever move from the Romanian government that’s been in place since 2003. It’s designed to incentivize developers to stay home, rather than chase a bigger salary abroad.

Romania, which joined the EU in 2007, is one of the poorest countries in the European Union. Thanks to EU freedom of movement rules, which allow citizens of EU countries to seek employment opportunities in any of the other 27 EU member nations, Romania is at risk of losing its brightest and best. But thanks to this ingenious tax break, it’s managed to stave off the worst of a developer brain drain.

But first, a bit of history.

To understand why this tax break exists, it’s crucial to understand the politics and history of Romania.

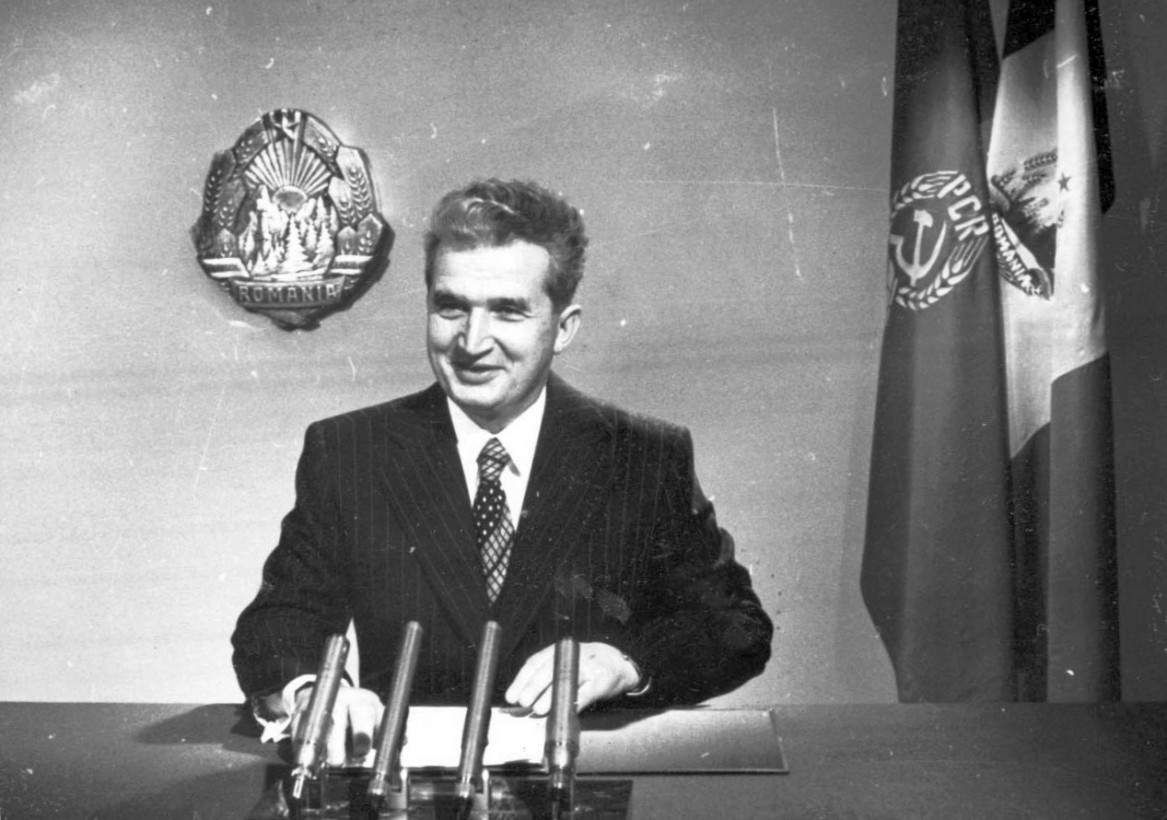

After World War II, Romania found itself on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain. From 1947 until the gruesome execution of loathed dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1989, the country was run by a succession of authoritarian communist governments, each more ostentatiously awful than the last.

The funny thing about authoritarian governments is that they’re empowered to change the destiny of a nation with the stroke of a pen, and that’s exactly what happened in Romania.

Overnight, the education curriculum was changed to emphasize science and (particularly) math. Consequently the country’s universities pumped out a near-constant flow of world-leading scientists and mathematicians, who worked in government laboratories and enterprises.

By the end of the fifties, Romania – which today has a population roughly one third the size of the UK – was one of only eight countries with the capability to domestically produce its own computers. That’s no small feat, given the nascent nature of the technology, and the inherent complexity in early-era computers.

It’s more than a little bit ironic that an ideological system so vehemently opposed to entrepreneurship and free market capitalism would create the conditions for such a system to flourish, but that’s exactly what happened in Romania.

When communism fell and the Soviet Union dissolved, Romania (like the rest of its neighbors) was in a state of shock. The internal and regional markets had effectively collapsed, and large government employers began to shed workers. Although it ultimately led to better times, it was a difficult period in the country’s history.

The arrival of free market capitalism afforded these mathematicians and scientists – who were regarded as amongst the best in the world – the opportunity to launch their own ventures. Romania became a hotspot of IT outsourcing in Europe. Western European companies could access incredible talent at a fraction of the cost of a local programmer.

Put simply, they could get a Porsche-quality programmer at a Dacia-level price. It was a no-brainer.

Fighting the brain drain problem

As a country, Romania is uniquely susceptible to brain drain.

For starters, there’s the language factor. Unlike its neighbors, who speak Slavic-based languages (with the notable exceptions of Hungary and Moldova), Romania’s language is based on Latin. There are many shared words between Romanian, Spanish, and Italian. For example, the word for “floor” in Romanian is “etaj,” while in French it’s “étage.” As a consequence, it’s relatively easy for Romanians to learn other Latin-based languages.

Most of the older generation speak French as a second (or third – Russian was also taught in schools) language to varying levels, but the younger generation predominantly learned English. During my (admittedly brief) time in the country, I didn’t once encounter anyone under the age of 30 who was unable to converse with me in English. Many possessed strong American-tinged accents, which is a testament to the ubiquity of Hollywood movies and MTV.

And then there’s the fact that it’s extremely easy for Romanian people to emigrate elsewhere in Europe, courtesy of its EU membership. Besides cars and wine, one of Romania’s biggest exports is its people, who can be found working in offices and startups across the continent.

It’s understandable to see why Romania is eager to keep its tech talent within its boarders. Schools are good, and universities are largely funded by the government. Naturally, it doesn’t want to spend money educating someone, only to see them emigrate and pay taxes to a foreign nation – like Germany, France, or the UK.

Freedom of movement has been good for Western Europe and Romania’s people. But has it been good for Romania as a whole? It’s not entirely clear.

But there’s another little-discussed factor worth mentioning: those who emigrate tend to be risk-takers, and are more likely to launch startups and hire other people. They tend to possess the types of personal characteristics that drive innovation, and are essential for economic growth. This phenomenon can also be seen in the US, where a disproportionate amount of Silicon Valley’s biggest companies are either founded or run by first- or second-generation immigrants.

Can this system work elsewhere?

Before you start packing your bags and buy a ticket to Bucharest, there’s a couple of caveats that I should mention.

Firstly, although developers don’t have to pay income tax, they still have to pay for social security contributions, which are somewhat steep. This is analogous to National Insurance in the UK; separate from income tax, but a tax nonetheless.

Although Romania is a cheap country (my breakfast one morning cost me 4.5 RON, which is about $1.10), the country has a relatively high sales tax, which inflates the ticket price of many consumer goods. Moreover, despite the tax break, salaries for developers are still low compared to Western Europe and the United States.

In short, this tax break is suited to disincentivizing emigration, rather than encouraging inward immigration.

It’s not uncommon to see governments use the tax code to shape the labor market. A good contemporary example would be the tax break offered by the Trump Administration to Taiwanese manufacturer Foxconn.

In exchange for $4 billion in tax relief, Foxconn will build a massive factory in Wisconsin, which will hire 13,000 locals in a state that’s been devastated by the deindustrialization of the West that’s taken place over the past 20 years.

This deal isn’t without its critics. Many have argued that this deal doesn’t offer taxpayers value for money, but that’s a point for a separate article entirely.

However, what is notably uncommon is to see governments use the tax code on a personal level, and prioritize certain professions over another.

Could this work in an affluent, developed country like the UK or US? I don’t think so. Developers are drawn to London and San Francisco for a variety of compelling reasons, like higher salaries, better employment opportunities, and the chance to develop your career by working in a fast-paced and innovative startup.

Having spoken to hundreds of developers that have moved to London and San Francisco over the years, I’m yet to hear one mention taxes as a deciding factor in their immigration stories.

But what about developing and middle-income countries like India and China, who both possess excellent universities, but are experiencing massive outflows of talent to the West? Could such a tax break convince Indian and Chinese techies to stay home and build the domestic tech scene?

It’s not clear. What is clear is that pitching a tax break for a privileged, educated few will be a hard pill to swallow in countries where many are living on less than a dollar a day. But as Romania’s example shows, this strategy can create the groundwork for further economic growth in the long run, and help lift more people out of poverty.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.