Just beyond the reach of charged particles from our Sun (which is, in some ways, the edge of our solar system), the Voyager spacecraft have witnessed a previously-unseen phenomenon for the first time.

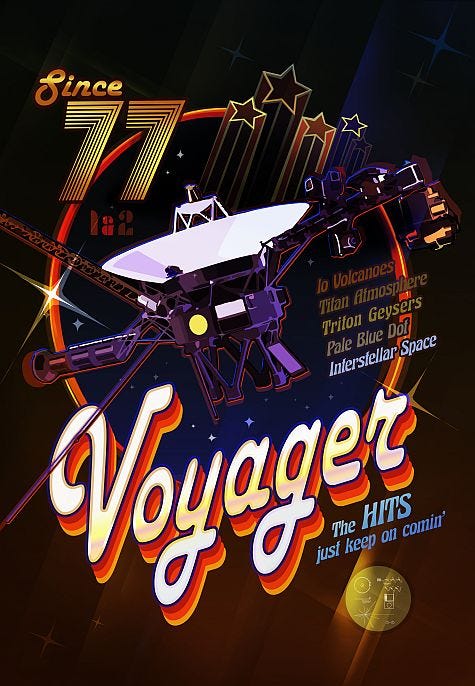

The pair of Voyager spacecraft, launched from Earth in 1977, are now in the shallows of interplanetary space. Despite being launched four decades ago, this pair of robotic explorers is still making new discoveries, as they traipse through uncharted territory.

“The Voyager 1 (V1) and Voyager 2 (V2) spacecraft were launched in 1977 on a mission to explore the outer planets and reach the heliopause, the boundary between the hot solar plasma and the relatively cool interstellar plasma… One of their remarkable discoveries was the detection of shocks propagating into the interstellar plasma from energetic solar events,” researchers wrote in an article, published in The Astronomical Journal.

Why is everyone so negative about electrons?

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) from the Sun expel shock waves of hot gas and energy at speeds around 1.6 million kilometers per hour (one million MPH). Even at speeds that could circle the Earth 40 times a second, it still takes nearly a year for these shock waves to reach the Voyager spacecraft.

Cosmic ray electrons — negatively-charged subatomic particles racing from the Sun — are propelled by shock waves from a powerful stellar eruption. This form of radiation has been theorized previously, but cosmic ray electrons have now been seen for the first time, by both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.

“What we see here, specifically, is a certain mechanism whereby when the shock wave first contacts the interstellar magnetic field lines passing through the spacecraft, it reflects and accelerates some of the cosmic ray electrons,” explains Professor Don Gurnett of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Iowa.

These cosmic ray electrons race through space at nearly the speed of light — roughly 670 times faster than the shock waves that originally propelled them. Several days later, a second wave of slower, lower-energy, electrons arrived at the spacecraft. The shockwave itself arrived at these distant reaches of the Solar System nearly a month later.

Electrons in the interstellar medium between stars are reflected by the magnetic field at the edge of our Solar System. The motion of the shock wave, ejected from the Sun, accelerates the wave through the magnetic field. These electrons then spiral along the magnetic field lines, gaining speed, as they travel away from the shock.

“The idea that shock waves accelerate particles is not new. It all has to do with how it works, the mechanism. And the fact we detected it in a new realm — the interstellar medium — which is much different than in the solar wind where similar processes have been observed. No one has seen it with an interstellar shock wave in a whole new pristine medium,” Gurnett explains.

Examination of these processes could help astronomers learn more about exotic flare stars, which vary brightness to an extreme degree, driven by storms on their surface.

Learning about these storms will also assist NASA, SpaceX, and other organizations looking to place space colonists on the surface of Mars. Such lunar or Martian colonists would be exposed to far higher levels of radiation than we experience on Earth.

A space in the hole

“V’Ger must evolve. It’s knowledge has reached the limits of this universe and it must evolve. What it requires of its god, Doctor, is the answer to its question, ‘is there nothing more?’” — Commander Spock, Star Trek: The Motion Picture

Launched in the age of disco, the twin Voyager spacecraft from NASA were sent on a mission to explore the outer Solar System. The mission took advantage of a rare alignment of planets, allowing an easier journey around the giant worlds.

Currently 22.5 billion kilometers (14 billion miles) from Earth, the Voyager spacecraft are the most-distant human-made objects anywhere.

Cosmic ray instruments onboard the Voyager spacecraft revealed electrons seen by the detectors were reflected and accelerated by solar eruptions.

“Barring any serious spacecraft subsystem failures, the Voyagers may survive until the early twenty-first century (~ 2025), when diminishing power and hydrazine levels will prevent further operation. Were it not for these dwindling consumables and the possibility of losing lock on the faint Sun, our tracking antennas could continue to “talk” with the Voyagers for another century or two!” NASA describes.

The edge of the Solar System can be defined in a number of ways. The heliopause, where the streams of charged particles from the Sun give way to the interstellar medium, was recently passed by the Voyager spacecraft. However, gravitational effects from the Sun stretch out much further — to the Oort Cloud — a diffuse group of rocky and icy material surrounding our Solar System. These intrepid robotic explorers will not reach this distance for tens of thousands of years.

Although the two Pioneer spacecraft were launched before Voyager, these two craft are not as fast as Voyager. Pioneer 11 is due to leave the Solar System in 2027, and in 2043, New Horizons (which explored Pluto) will pass that mark. Finally, in 2057, Pioneer 10, the first of these spacecraft to launch (on March 2, 1972) will pass the outer particle boundary of our solar system in 2057.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.