What would a social media feed be without monsters? I’m talking figurative monsters here; your racist uncles, your Trumps, your worst influencers – people so terrible you have to read everything they say and see everything they post.

Despite their awfulness, we can’t go without them. Buy why? My theory is that these people exist in your feed as a contrast agent, a reminder of awfulness that makes the good stuff stand out more, sometimes comically, sometimes aggravatingly.

Believe it or not, there’s a parallel to be made between monsters illustrated in the margins of medieval books by monks, and the people we follow on social media out of morbid fascination. Hear me out.

Both the monsters in our feeds and the monsters in the margins play a similar role; they frame the content we might actually be interested in, contrasting the interesting and useful with the vile and terrible.

View this post on Instagram

“For medieval people, monsters were necessarily part of Creation. God created the world and its inhabitants, and therefore created monsters. Why would he create monsters, though? Monsters usually represent the ‘dark’ side of the world, sins against Christian virtues. The representation of monsters precisely reminds people of the ever-present, attractive, and deceitful world of pleasure, lust, and greed.”

For modern people, modern monsters play much of the same role. But instead of being doodled by monks, they are created by the clerics of our day, the media, and us, on social media. They might not be outwardly as atrocious, but the qualities ascribed to them serve the same role. Take a medieval monster like the Cynocephali – a mythical species of dog-headed people, that often was used to represent the ‘uncivilized’ Scandinavians or Africans.

In media nowadays, both social and traditional, people are (justly or unjustly) vilified to represent the underbelly of whatever your surroundings’ fear du jour is. Like the monsters in Medieval margins, they normally exist far from home, but close enough to feel threatening.

Ironically, the way I bumped into this parallel was on Twitter.

The above quote about Medieval people came from Dr. Damien Kempf, a historian with the University of Liverpool, who, together with his late wife Maria L. Gilbert, wrote a book called Medieval Monsters, about well, you can guess.

The Monster of Cracow@WellcomeLibrary, Pierre Boaistuau, Histoires Prodigieuses, 1559 pic.twitter.com/MIO6hckYus

— Damien Kempf (@DamienKempf) July 12, 2016

Kempf also runs a Twitter and Instagram account where he shares the best monsters they found while scouring massive online archives of Medieval books, which are available courtesy of libraries or universities.

The rise of social media has led to the flowering of a lively scene of medievalists, historians, and archivists sharing what they find online.

Where Kempf specializes in monsters, others, like book historian Erik Kwakkel, post shots of interesting pages they find in ancient manuscripts. Others, like Dr. Johanna Green, highlight the beauty and fine detail of the illustrations. Others again make good fun of the illustrations – treat yourself to Daniel Mallory Ortberg’s Two Monks Inventing Things series on The Toast as an example.

View this post on Instagram

Kempf aims to highlight the scary, the beautiful, and the funny: “sometimes [I] get frustrated when I read that Medieval monsters have to do with anxiety, ideology, propaganda – what about the fabulous, even wacky imagination that gave birth to them on the pages of a manuscript or sculpted decor of a church?”

He’s not exaggerating when saying wacky. Check out this little dude:

View this post on Instagram

I laid out my thoughts on the parallel between the functions of metaphorical monsters nowadays and illustrated monsters back then, hoping that Kempf would not laugh at me. He didn’t, luckily, but he did tell me more about the functions monsters served in the books.

“I do not think there can be a single, definite answer to it. Let’s note, first, that the books where we find most of these monsters were religious books such as the Bible or Book of Hours, that is, book of prayers made for lay individuals. Depictions of monsters often appear in the margins of the page. Sometimes, they seem to be a commentary upon the text they surround, but most often they have no direct relationship with it. In other words, they do not have a purely ‘illustrative’ function in the sense that they rarely illustrate the text around them. They constitute a world of their own. Monsters occupy the margins of the page in the same way they are believed to inhabit the edges of the known world.”

Ok, so that checks out. Our modern day monsters (in the affluent west which skews my perspective), like ISIS for example, live in far-flung places.

View this post on Instagram

“Monsters such as devils were obviously represented to scare people and to remind them of their sinful condition, to remind them that one should always strive to live according to Christian ideals.”

Again, that checks out if you replace ‘Christian ideals’ with ‘neoliberal surveillance capitalism.’

“There is, however, also an entertaining function that we cannot undermine, and which is much more difficult to assess. Some monsters are indeed so comical that we cannot but smile, or even laugh, when looking at them.”

We lose 300 Americans a week, 90% of which comes through the Southern Border. These numbers will be DRASTICALLY REDUCED if we have a Wall!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 11, 2019

Other monsters are sublimely weird, in a way that makes you wonder about the mental sanity of the monks who spent their lives copying Bibles and drawing fantastic beasts like these – maybe on their breaks? Or maybe just to make their neighbors laugh?

As Dr. Kate Wiles writes in an article for History Today, it isn’t and hasn’t been clear why some of the drawings were done. Wiles quotes 12th century French Abbot St. Bernard of Clairvaux as writing, “What profit is there in those ridiculous monsters, in that marvelous and deformed beauty, that beautiful deformity? To what purpose are those unclean apes, those fierce lions, those monstrous centaurs, those half-men…”

When the illustrations aren’t depicting more or less what’s going on in the text, Wiles writes that theories behind them range from illustrations being purely decorative to acting as mnemonic devices to help memorize the text. But for us modern humans, the appeal is easier to pinpoint.

Wiles words this better than I could: “In many cases, their inexplicability, borne from their lack of context, only makes them more intriguing. It is not necessary to be an art historian of the Middle Ages to appreciate them.”

Kempf agrees with that last bit. He wrote to me that “The majority of my exchanges on social media are with non-academics, which I find particularly rewarding given that my aim in posting medieval images on Twitter and Instagram is precisely to reach out to people who are not specialists and would not otherwise encounter these images.”

This might also be because professional historians might not totally be on board with the merry sharing of Medieval manuscripts just yet: “Academics used to be quite reticent, if critical, with regard to social media – things have gradually changed and more of my colleagues now use it as a way of sharing their work not only with other colleagues but also with the wider public. “

And a wide public it is indeed, clocking in at close 100,000 followers over Twitter and Instagram. This number pales in comparison to, say, one of the Kardashians, but remember it’s an account posting pictures of illustrations that were done in the margins of ancient books and manuscripts.

To Kempf, the appeal is obvious. “I sort of knew they would spark interest: as I mentioned earlier, the medieval aesthetics of monsters is very cartoonish and often comical, and it easily catches the eye!” he writes.

When you spend too much time on Twitter

[BL, Arundel 83, 14th c.] pic.twitter.com/eyRZXFZJbP— Damien Kempf (@DamienKempf) July 23, 2018

“Skeletons with a goofy smile are always a hit,” he writes. “Devils are also very popular, particularly the ones with deformed bodies (with faces on buttocks and knees) and foolish facial expressions. The weirder the image, the better it works, generally. “

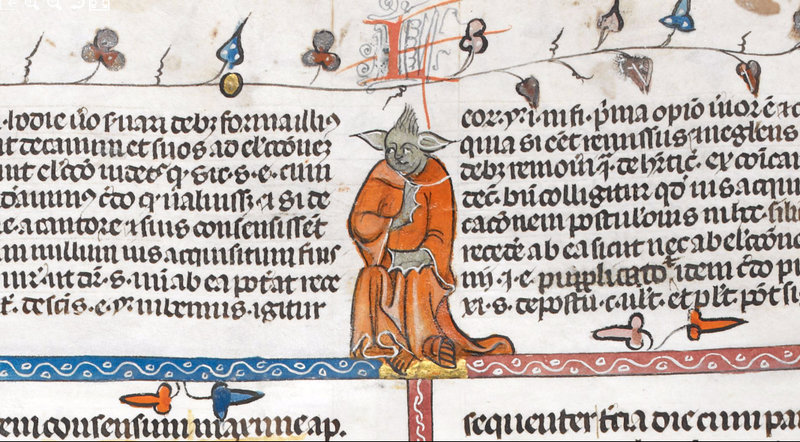

There are even some medieval monsters that are symbolically relevant to our age – in quite different ways. You’ve probably seen medieval Yoda, which was found by Kempf.

But when I asked about others, Kempf quickly had a better example for me: “The monstrous frog coming out of the mouth of the false prophet seems to embody a lot of what is going on in politics nowadays…”

The False Prophet

[BnF, Latin 8878, 11th c.] pic.twitter.com/bITxPlntaq— Damien Kempf (@DamienKempf) November 8, 2018

The relevance to us is completely different to the one they had when they were drawn, of course. According to Kempf, studying them gives historians “a window into people’s imagination, how they imagined, and feared, the existence of beings that are different, the ‘others’. Now, the very process of defining the ‘other’ helps the construction of one’s own identity. Who am I in relation to someone else, the ‘other’? Studying monsters, therefore, is as much about imagination, dreams, fantaisies, anxieties as it is about social construct and hierarchy.”

Which brings us back to the monsters in our feed. How will future historians look back on the way we paint and perceive the evil, vile, and terrible of our present? Will they look at them and label our period as backwards, like we do for most of the Middle Ages? Or will they see how we respond to our monsters and take that into account?

Kempf: “People often refer to the medieval period as the ‘Dark Ages’ (so anything backward is conveniently labelled ‘medieval’), a period of intense social and religious control, and censorship. But it was also a period full of humor, wit, grotesque and laughter, which is perfectly reflected in the way medieval people imagined and depicted monsters.”

I’d like to believe we have a measure of control over how we’ll be characterized in the future. We are all the monks painting our monsters now.

If there’s anything we can learn from Kempf’s work it might be to not get sidetracked by the monsters in the margins, unless those monsters were drawn centuries ago by bored monks. Give future historians a chance to look back at the monsters of our age and marvel at them and ridicule them, much like Damien is doing for the medieval ones now.

In the relentless onslaught of news cycles it’s hard to zoom out and see the bigger picture. It’s also hard to zoom in and see things for what they are. I think that’s what interested me so much about the monsters in the margins; they’re both minor details in bigger work, and at the same time a unique insight into the fears, humor, and worries of another age.

And in the meanwhile, try to enjoy them as the marginal side notes in history they probably will be.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.