Pop quiz time: What’s estimated to be worth between $5 and $10 billion by 2020 and is (at least, in my humble opinion) largely bullshit?

Answer: Influencer marketing.

Okay, let me clarify something. The idea of paying people with huge amounts of reach to advertise your products isn’t dumb. Celebrity endorsements are a thing, and have been known to work wonders for brands. Think about LeBron James’ nearly $1 billion deal with Nike, or George Foreman with his eponymous lean, mean, fat-reducing grilling machine.

Online influencers, on the other hand, are a different kettle of fish.

Christ, just let it roll off your tongue. Influencers. It’s one of those words that sounds really grubby, doesn’t it? A bit like phalanges, or dongle. I don’t know about you, but the idea that someone identifies foremost with their ability to influence other people just rubs me the wrong way.

Thing is, they’re very seldom actually influential. At best, most are just really photogenic. And the entire industry serves as a tool to separate clueless brands from their marketing budget.

Bloggers or blaggers?

Social media services have always shown an uncanny ability to raise the profiles of their most prolific users. MySpace, for example, gave us Jeffree Star, who now owns a veritable cosmetics empire.

Similarly, platforms like Snapchat, Vine (RIP), Instagram, and Twitter brought countless more people to the attention of the world. Along the way, many realized that they could make money from their accounts, or use their profiles to get free products and trips.

Some of this blagging is actually pretty brazen. Earlier this year, an Irish hotelier received an email from vlogger Elle Darby, who wrote:

“My partner and I are planning to come to Dublin for an early Valentine’s Day weekend. I came across your stunning hotel and would love to feature you in my YouTube videos and recommend others to book up in return for free accommodation.”

Obviously, the hotelier published her email to his Facebook page, which promptly went more viral than a nasty case of swine flu. Things blew up, and faced with her own notoriety, Darby published a teary video where she “set the record straight.” Sadly, that’s since been deleted, but the internet never forgets.

At the time, Darby had around 87,000 YouTube subscribers, and most of her videos at that time averaged around 15,000 views.

Let’s do some back-of-the-napkin math. Dublin is a notoriously expensive city, with a chronic shortage of hotel rooms. Furthermore, Darby was looking for accommodation during the busy Valentine’s Day period, which pushes the average nightly rate higher.

So, let’s guesstimate that she’s looking for about £750 worth of free accommodation, which translates to roughly $1,000. Divide that by the average number of views her videos were receiving at the time, and the hotel is looking to pay £1 (or $1.30) for about 20 views of a video that mentions it.

That’s pretty crap. For context, you can dump about $7 into YouTube’s ad system and get around 2,000 impressions.

By and large, online influencers don’t represent good value for money. And that’s when they actually follow through. Quite often, they take the product and cash, and leave brands high and dry.

This is something that’s rife. According to a 2017 study from influencer fraud agency Sway Ops, around 15 percent of influencers who agree to promote a product take the item, but fail to produce any content around it.

This trend affects both small companies and huge global brands. Recently, Snap’s PR firm, PR Consulting (PRC), paid actor and Instagram personality Luka Sabbat an eye-watering sum to promote Spectacles.

Sabbat got $45,000 upfront, with a further $15,000 upon the completion of the deal. Here’s what was expected of him, according to TechCrunch:

He was contracted to make one Instagram feed post and three Stories posts with him wearing Specs, plus be photographed wearing them in public at Paris and Milan Fashion Weeks. He was supposed to add swipe-up-to-buy links to two of those Story posts, get all the posts pre-approved with PRC, and send it analytics metrics about their performance.

Obviously, he didn’t come close enough to that, and now the PR firm wants its money back.

Fraud, glorious fraud

By and large, the influencer marketing space is rife with fraud. It’s like if Herbalife and Amway had a lovechild, and the baby insisted on perpetually talking shite into a camera.

Last year, Sway Ops found that almost 50 percent of fraudulent interactions on Instagram took place on posts tagged #ad or #sponsored. I presume this is to convince brands that their advertising spots are performing better than they truly are.

With brands more inclined to spend their precious advertising dollars on the influencers with the most reach, influencers are incentivized to play dirty. Broadly speaking, this manifests itself with fake followers, and bots leaving comments and likes.

The good news is that brands are increasingly aware of this. In June of this year, Unilever’s marketing boss, Keith Weed (that’s his real name) said that the company would refuse to work with anyone using these underhanded tactics.

“The key to improving the situation is three-fold: cleaning up the influencer ecosystem by removing misleading engagement; making brands and influencers more aware of the use of dishonest practices; and improving transparency from social platforms to help brands measure impact,” Weed explained.

“We need to take urgent action now to rebuild trust before it’s gone forever,” he added.

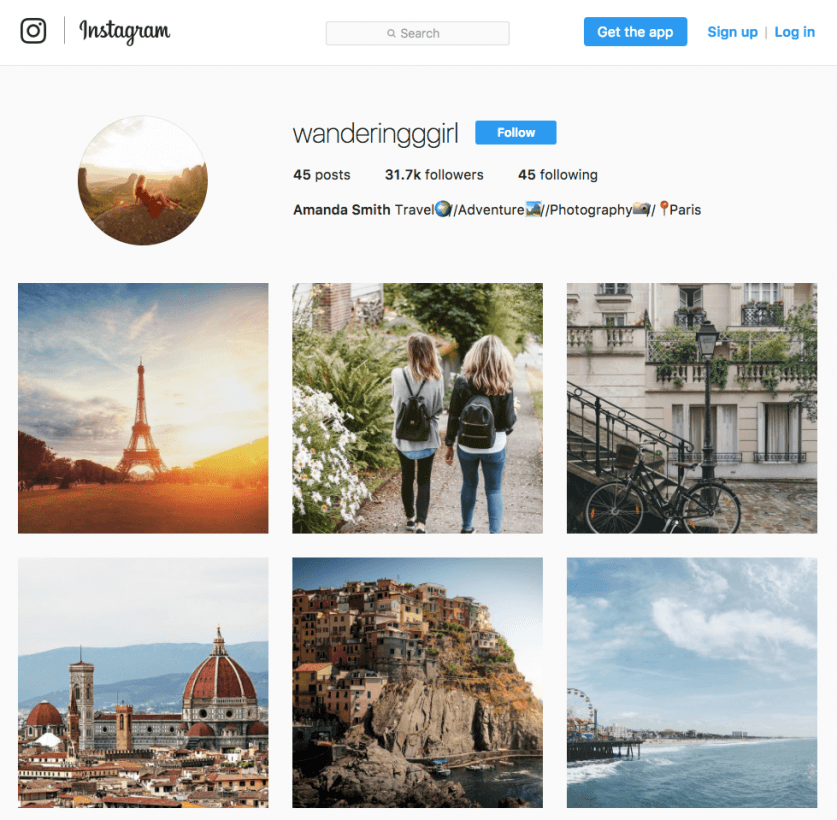

But unfortunately, some are still getting caught out. Earlier this year, marketing agency Mediakix created two fictitious Instagram accounts focusing on travel and lifestyle respectively. The experiment was to see how far you could take a fake account.

Both accounts had a healthy amount of followers and engagement — paid for, of course. In the case of the travel account, Mediakix were bold enough to just use stock photographs of exotic locales, pilfered from other parts of the internet.

It didn’t take long for brands to start lining up to offer sponsorship deals. The totally fake travel account, for example, secured deals with an alcohol brand, as well as a national food and beverage company.

It’s worth noting that this chicanery isn’t limited to Instagram. Twitter, for example, is filled with accounts that boasts hundreds of thousands of followers, while simultaneously following hundreds of thousands of followers.

If you’ve ever been followed by an account, only to be unfollowed seconds later, odds are high that person is using a script designed to inflate their follower numbers.

What the hell is an influencer anyway?

I guess my biggest gripe with influencers isn’t the grubby nature of it, or the fact that many accounts are thinly veiled tools for fraud, but rather the fact of how grubby and nebulous the term is.

What is an influencer?

One explanation creates two separate camps, with the likes of Zoella and Logan Paul in one section, and “micro-influencers” in another. These are people who have over 15,000 followers, which is the threshold to be considered by some brands for sponsorship deals.

But what about the tens of thousands of people who identify as influencers, despite having only a handful of followers? You don’t have to look far for them.

I don’t think these people cheapen the term “influencer,” because it’s already pretty much worthless. However, I do find it more than a little bit sad that people aspire to be one.

Please let it all end

So, in conclusion, the term “influencer” is nebulous at best, with no clear definition. Literally anyone can call themselves an influencer, despite the fact that most aren’t actually influential in any meaningful sense.

Furthermore, the field is filled with the worst types of opportunistic and dishonest actors. Fraud is rife, perpetrated largely by automated bot accounts hired out by those seeking to increase their own profile. This happens on almost all social media platforms.

And, I’m sad to say, this has done nothing to dent the stratospheric rise of influencer marketing. As long as there are brands eager to take advantage of alternative marketing channels, there will be an army of photogenic young vloggers eager to take their money. But that doesn’t mean I can’t be grumpy about it all.

So, what can be done? One idea is to have influencers abide by a code of ethics, similar to those journalists work under. They could pledge to never use bots in order to artificially augment their traffic and reach, and promise to ensure sponsored content is clearly labeled as such.

I’m skeptical about that, because influencers aren’t journalists. There’s no editorial process. There isn’t an editor-in-chief barking commands, and ensuring that everyone toes the line. They exist solely to be tools for marketing products and services — that’s it.

So, perhaps the burden to fix influencer marketing lies on the shoulder of brands. Like Unilever, they could promise to never work with bot accounts, and to treat each engagement with an influencer like an actual business deal, ensuring they hold up their side of the bargain when they agree to market a product.

With influencer fraud now a $100 million problem, this seems like the most inevitable outcome.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.