Commercial ebook publishing and distribution is a crowded space: Amazon, Apple, Google, Barnes and Noble and others each have stores and devices for digital books, which have been seeing consistent growth. Ebooks are undoubtedly the future of long-from content. They’ve opened up a whole range of new publishing opportunities for independent authors, and the significance of being able to self-publish books so cheaply and simply should not be underestimated.

For the most part, the focus on ebooks has been commercial. One area that’s underrepresented: free contemporary ebooks. While many exist, and most commercial ebook stores like Amazon and Google Books have some free ebooks, there’s no central source for readers to download free ebooks or for authors to distribute them under more lenient licenses like Creative Commons.

With Leebre, Michael Bethencourt — a 22-year-old free software and free culture fan who graduated with a Computer Science degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison — plans to change that (Bethencourt’s previously contributed to open source projects like Google’s MOE and the games Nexuiz and Warzone 2100, and during college he did internships with Microsoft, Facebook and supercomputer company Cray). “Right now, there aren’t really any good communities for independent authors to publish their works, and certainly none focused around free culture,” he says. “Furthermore, independent authors have no easy-to-use tools for making ebooks or nicely formatted online books, so self-distribution and self-publishing is really hard, unless they have technical knowledge.”

“Leebre intends to fill this gap: provide a community and tools for independent authors to publish their work and get noticed,” says Bethencourt. “In 2010, I received a Nook as a gift, and was rather dismayed to find that there was no huge repository of fresh, free fiction, just like I was used to for music,” he says, referencing Jamendo. The repository for free music from independent artists was a huge inspiration to him, and he wants Leebre to provide similar resources and community to independent authors.

A community of readers and writers

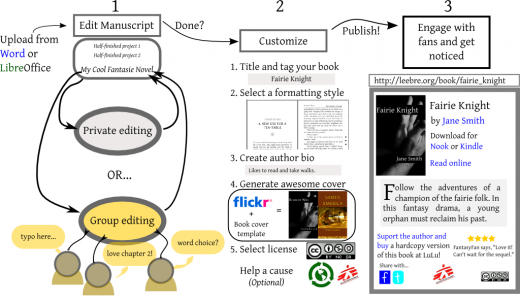

Bethencourt has an ambitious vision for a community platform that will both give authors an easy way to format and share their work, and readers a place to find free books and connect with their favorite authors. A cornerstone of Leebre, like Jamendo, will be the driving free culture philosophy and use of Creative Commons for licensing. However, Bethencourt’s vision goes far beyond website simply for Creative Commons books to be hosted and shared. The community, especially, is what he hopes will differentiate Leebre from popular ebook stores like Google Books and Amazon. “The key to (for example) YouTube’s success wasn’t that it was simply a host for videos, but that it was a social platform built around videos,” he says. “Readers like being able to connect with authors, and vice-versa.”

Readers can support authors through donations and links to other sites that sell books, like Amazon and Lulu. Bethencourt doesn’t see services like these as competition; instead, Leebre is “intended to complement them.”

One of the more interesting ideas he has for the donate button: authors can choose to support a cause and have donations directed to a non-profit of their choice. “I hope to see even established authors distribute short stories or books on it in order to fundraise for a cause,” he says.

Each book will be downloadable in ePub, MOBI, HMTL, and PDF, and can be read online as well.

Leebre for authors

Of course, the most important part about a website for book lovers is the selection of books. But Bethencourt isn’t worried about that part. The feedback he’s seen from authors has been positive and supportive. He expects it to be a platform where works that might not otherwise be published will be given a chance. Short stories, for example — “anyone who has completed a Creative Writing degree (and I know this since I took several creative writing classes while in college, which have definitely influenced my design decisions) will have probably 5 or 6 or so rather decent short stories which are basically un-publishable through conventional means.” Novels are much more of an investment from authors, but he expects a strong community, the donation system, and the opportunity to get noticed will “be enough to offset trepidations about posting it for free.”

“With my discussions with authors, it would seem the biggest barrier isn’t ‘not wanting to give them for free’, but rather just the effort of putting them online, and in a place people would download them,” says Bethencourt, “The authors I’ve shown the website to barely bat an eye at the idea of posting their work for free: they’re generally just enthralled to put it up somewhere, and not have it rot on their hard-drive looking like crap.”

A major draw for authors — and an integral part of the platform and Bethencourt’s vision for its future — is an online book editor. It’s how books are uploaded, and it’s how every author will be able to have a professional looking ebook without having to worry about formatting and design.

Everything on Leebre will first go through the online editor (built entirely using HTML and JavaScript), to ensure a high quality, consistent display of all books, regardless of the format. Authors can either upload their books (as a .doc, .docx, .odt, .html, or .epub) or simply copy and paste the text in, which actually works better, according to Bethencourt (and it means you can upload a book from any source that supports “copy”). Then the system parses the text and “guesses” at what’s what — dedication, chapter headers, prologue, endnotes, footnotes, etc. The author then gets a chance to check whether the system guessed right, but he says it usually does, “especially if you are uploading as an ePub which gives a few more clues than, say, Word.” The book can be worked on within the editor, and Bethencourt has plans for group editing and “crowd-sourced” editing.

Semantic book editing

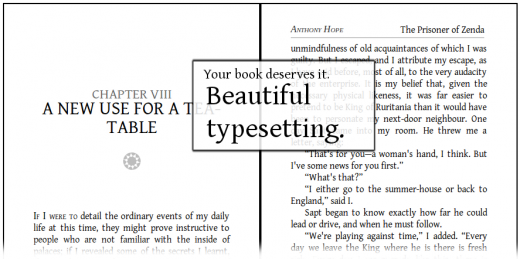

This is all done with the help of an internal format that Bethencourt’s currently calling “SemBook” for Semantic Book, because it “encodes the book in a very semantic way. That is, it retains much more of the author’s intent than ePub or MOBI.” Instead of using normal formatting tools — bold, font size, etc. — to set how each chapter header, footnote and everything else looks, everything is specified as what it is (chapter, footnote…). Then, depending on the style chosen, everything will be formatted automatically. “It is inspired by LaTeX, and so has a What You Mean is What You Get philosophy, as opposed to word processors and their What You See is What You Get,” says Bethencourt.

The use of the semantic format allows for some pretty cool things to be done. For one, it makes it really easy for a book to look good, without the author knowing anything about design. The author just makes sure everything is specified in the editor, and then chooses a styling template (there will be many to choose from). The template takes care of making everything look how it’s supposed to, and the look of the entire book can be changed simply by changing the template. “That way, it always achieves excellent formatting, no matter what the author originally submitted: the manuscript could be in 20pt pink Comic Sans, but the result will be the same across authors,” explains Bethencourt, “With Leebre, I want to even the playing field and give independent authors this same ‘professional’ look.”

In the future, this could become an even bigger part of the platform: “Eventually, I hope to connect graphic artists and people with experience in typesetting to authors, by providing standardized ways to specify templates to the graphic artists, and a similar community (with rating systems, comments, popularity metrics, and so on), to create and consume templates for books. This is to provide the largest possible selection to authors for style.”

The internal format also makes it easy for books to be published on Leebre in various formats. “As long as the author can get it into this [SemBook] format, it can be formatted extremely well as any other format.” For example, in the ePub and Kindle formats, anything specified as a chapter in Leebre’s editor will be designated as a chapter in the table of contents.

The format even recognizes more complicated elements like dialog, which allows quotation marks to be customized depending on language.

The semantic format pervades Leebre’s concept. But to almost everyone, it’ll be invisible (the only people who need to deal with it are developers and eventually designers). Authors upload a document or copy and paste their books to get them into Leebre; readers read them online or download them in ePub, MOBI, HTML, or PDF. Behind the scenes, SemBook makes it all work. “The semantic format is something only used internally, and is the ‘secret sauce,’ if you will, to getting automatic professional looking formatting, without using a typesetting program.”

Eventually, Bethencourt would like to spin the editor off and make it easy for other projects, like Project Gutenberg, to make use of it. “Project Gutenberg right now has a massive collection of public domain books,” he says, “but they are all inconsistently and sloppily formatted.”

Bethencourt sees the ease of publishing books with the online editor as something that sets Leebre apart from other ebook stores. “I’ve looked at Amazon some, and it’s not a simple task to turn your manuscript into a publishable ebook,” he says, “With Leebre, it is a very simple task, and the end product is polished, elegant, and to publishing standards. The online edition looks like a real paperback book.”

Where it stands

Bethencourt has been working on Leebre for just over a year. The core is nearly ready, although Bethencourt says “there are a few non-essential features that are unfinished (such as the rating system), and a few others which do not live up to my vision.” He plans to launch a private beta in mid-February, open to Kickstarter supporters and anyone who’s submitted a beta request. He wants it to be “stunning” before it’s available to everyone.

On Kickstarter, the project has passed its goal of $3000, for a virtual private server for the beta.

After the private beta, Bethencourt plans to open it up to those with .edu email addresses, and finally to the public. He hopes to involve more developers — currently, it’s only him, Rebecca Carvalho as publicist, and another developer that hasn’t started — and “get the software itself polished up and separate, so that projects like archive.org, Project Gutenberg, WikiBooks, and WikiSource can all benefit from better formatting.”

As far as financials, he plans to create a a 501(c) non-profit, making donations “easier and tax-deductible,” but is waiting until the project is more established. “I’m planning on going the route of other free software non-profits, like Mozilla, the Document Foundation, etc.,” he says. The project will be funded by donations, an occasional fundraising drive if necessary, and perhaps branded gear for sale, although it’s obvious that money is of little importance to Leebre, beyond what’s needed to sustain it. The project promises “100% dedication to the community and free software,” and that there “will never be ads, or any other sort of compromise of the site’s mission.”

“I plan on keeping it dedicated to the free software and free culture community,” Bethencourt says, “I want it to be the best tool for educators, writers, and readers, and so I intend to keep it non-profit.”

Along with the crowd-sourced editing feature, Bethencourt plans for online creativity workshops that mimic traditional creative writing courses and workshops, internalization (of the site, and of books, potentially through crowd-translating), and eventually, support for more diverse types of fiction like graphic novels and illustrations.

(Fre)ebook revolution

Jamendo, Flickr, Wikipedia and many other projects have proven that both the creators and consumers exist to make free projects work. The demand is there, and Leebre seems a welcome companion for both readers and authors. Bethencourt has a long road ahead of him to make Leebre succeed, with his ambitious vision as both its greatest asset and greatest challenge. Above all though, the project’s success will hinge on its community. It needs people willing and able to fill it with quality independent books. And it needs readers passionate enough to make it worth it. It’s an uphill battle, for sure — but for the sake of independent authors, readers, and the free culture movement, I hope Bethencourt succeeds.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.