Back in 2016, enterprise “private blockchain” was a new, unfamiliar idea. There were not many major players in the private permissioned blockchain space; a big name was IBM, whose contributions to Hyperledger Fabric has since brought its tech in front of the likes of Walmart, Nestlé, and Aetna.

You would think that the prominence and history of IBM’s brand would result in wide industry adoption of their blockchain tech, but instead, adoption has been sluggish and most solutions are still in the nascent proof-of-concept stages. This suggests that many of IBM’s enterprise customers are not satisfied.

The reason might be fundamentally about IBM’s technology; IBM’s Hyperledger isn’t really a “blockchain,” and what it does offer is hard to use and difficult to scale.

When I worked at JP Morgan in 2016, I led an emerging technology group that researched and vetted blockchains for the bank’s potential use and strategic investment. At the time, we did in-depth analyses of early versions of Hyperledger, Axoni, Symbiont, Tendermint, Ripple, and Ethereum.

My team discovered that the blockchain options in the market were technologically subpar for real enterprise use cases. These tech problems ranged from having code compiled down to computer “bytecode” that rendered business logic unreadable — and therefore hard to check for auditors — to running so slowly that one couldn’t perform helpful business transactions any better than with a traditional database.

We used to joke if we were to go to our bosses at JP Morgan and tell them that you couldn’t upgrade your business smart contracts in Ethereum without hard forking the entire network, we would be laughed out of the room.

So we came up with a list of questions that we asked at JP Morgan while looking at blockchain vendors. Questions like:

- What language will this blockchain use?

- Is the language designed for safety?

- Can the system easily express complex business rules?

- Can you upgrade your contracts, i.e. establish a governance regime over any contract?

- Can the system interact with external blockchains?

- Can the system add participants (nodes) without drastically slowing down performance?

Using these questions as a framework, I believe that blockchain requires architectural elements that IBM’s system fundamentally lacks.

I’m also not the only one who has since suggested that IBM’s performance claims don’t add up; and while my colleagues and I don’t see the numbers game (transactions per second, node count) as the only factor in blockchain adoption, we do think it’s important to educate people on what a blockchain is and is not. This education will hopefully help everyone better understand the landscape of this emerging technology.

What blockchain is and isn’t

In order to really understand where IBM’s blockchain fails to satisfy, we need to look at the very definition of a blockchain itself. A blockchain is a decentralized and distributed database, an immutable ledger of events or transactions where truth is determined by a consensus mechanism — such as participants voting to agree on what gets written — so that no central authority arbitrates what is true.

IBM’s definition of blockchain captures the distributed and immutable elements of blockchain but conveniently leaves out decentralized consensus — that’s because IBM Hyperledger Fabric doesn’t require a true consensus mechanism at all.

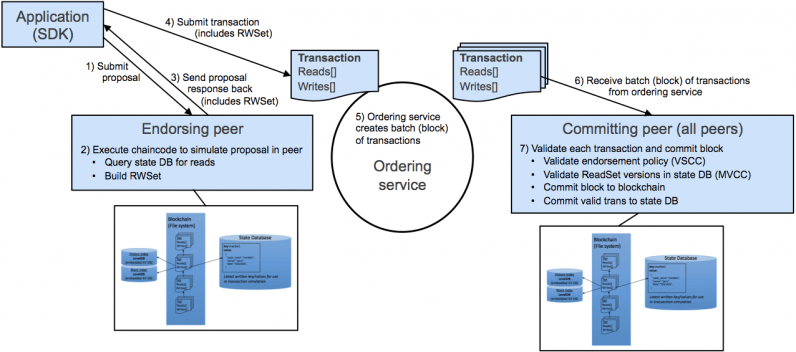

Instead, it suggests using an “ordering service” called Kafka, but without enforced, democratized, cryptographically-secure voting between participants, you can’t really prove whether an agent tampers with the ledger. In effect, IBM’s “blockchain” is nothing more than a glorified time-stamped list of entries.

IBM’s architecture exposes numerous potential vulnerabilities that require a very small amount of malicious coordination. For instance, IBM introduces public-key cryptography “inside the network” with validator signatures, which fundamentally invalidates the proven security model of Bitcoin and other real blockchains, where the network can never intermediate a user’s externally-provided public key signature.

In a Hyperledger node, the only signatures that matter for consensus are the validator’s, while the user signatures disappear into arbitrary data in the “RWSet” which is replicated through the network (see diagram below).

IBM plays very fast and loose with performance numbers due to their complicated architecture. The architecture, or shape of a blockchain, matters because it controls how information moves on the digital ledger.

The architecture of IBM’s platform is complex, involving non-uniform nodes, unreliable smart contracts, and many points of failure. Security-wise, its architecture provides assurance only within the system, meaning that there is always a risk that someone can subvert the intention of a user.

Moreover, the performance numbers that IBM Hyperledger Fabric claims are misleading. Hyperledger uses a multi-chain environment (they call them “channels”) as part of their confidentiality/network security. However, their transactions cannot be replicated across channels, meaning each channel should be evaluated independently from a performance point of view.

When looking at individual channels, IBM’s system struggles to get above 800 tps, but even a 16-channel configuration can barely get above 1500 tps, with latencies reaching well into the 10-20 second range at the upper throughputs.

Why smart contracts matter

The final point of consideration consists of the smart contract languages used to program commands in a blockchain. A smart contract is not just a piece of code; it is a representation of business logic.

A smart contract may secure a house on the blockchain, assure a digital identity, or even just represent an escrow transaction between people buying and selling an old TV. It is important that a smart contract is reliable and always does what it says it will.

When it comes to building anything on a blockchain, you need to be able to represent what you want to do (buy, sell, package data, etc.) through smart contracts. The easier or simpler your language is to use, the faster you will build the thing you want and get it in front of the eyes of stakeholders.

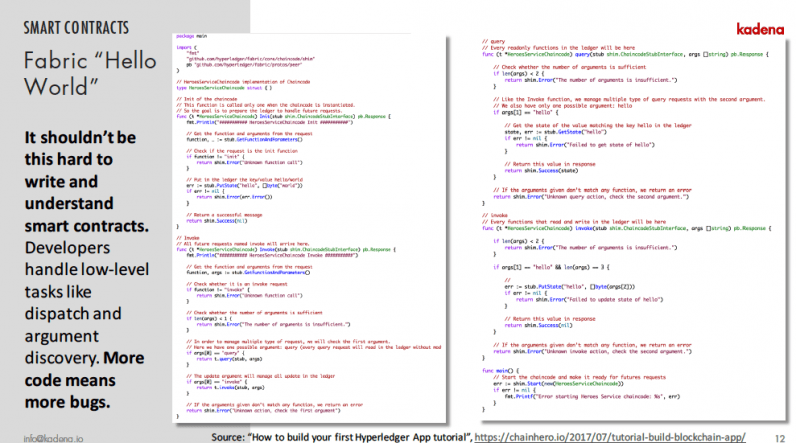

IBM Hyperledger Fabric smart contracts (“chaincode”) can be written in a number of programming languages including general Javascript or Go. Supporting multiple languages might seem beneficial because it allows people to pick up blockchain without necessarily learning a new language.

But there are trade-offs between the convenience of a programmer already knowing a general purpose language and the security and safety that a domain-specific language provides. When the stakes are as high as in blockchain — where millions of dollars can be lost if code is buggy or incorrect because it wasn’t designed for blockchain — the smart contract language must be purpose-built and safe by design.

Finally, if programming languages are measured by user-friendliness, then coding for Hyperledger isn’t exactly simple. In order to spell out the classic programmer intro sequence of telling a computer to say, “hello world,” you needed 150 lines of code that look like this:

The takeaway

While IBM still dominates a lot of the enterprise blockchain press cycle with their relationship announcements, it‘s important to look under their hood at what the technology actually can do.

When I participated in evaluating the tech at JP Morgan, we found that IBM’s technology did not stand up to its performance claims and definitely was not offering the simplest or safest solutions for digital ledgers. I believe that challengers will arise offer better tools, better blockchains, and a better vision for the future of our society and how we use technology.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.