Disclaimer: nothing in this article should be constituted as mental health advice. This is anecdotal evidence from a technology journalist.

I’ve been a gamer since the early 1980s. I cut my teeth on Tempest and Donkey Kong in the local arcade. Gaming is my solace.

When big things happen in my life or in the world, and I need to wrap my head around them, my go-to coping mechanism is to play a game until I can think clearly and focus. This is how I’ve always blown off mental steam (for lack of a better way to put it).

But something happened in 2020 that changed everything: video games stopped working for me. The pandemic hit, the protests happened, and my mother passed away without a funeral. My mental health absolutely tanked before Thanksgiving.

When I tried to play my favorite games such as Modern Warfare and Red Dead Redemption II, I’d end up zoning out after a few minutes. More often than not, I’d load up a game on my big screen and sit at the menu for an hour while I doomscrolled Twitter on my phone.

It might not seem like a big deal, but to me this was the mental-health equivalent of losing my gym membership.

Luckily I’d manged to really get into “LA By Night,” by then. For those unfamiliar, it’s a TV show featuring a cast of actors streaming their tabletop roleplaying session of Vampire: The Masquerade.

While researching the IP and the people behind it I learned Paradox Interactive, a company known for its strategy video games, was in charge of the property.

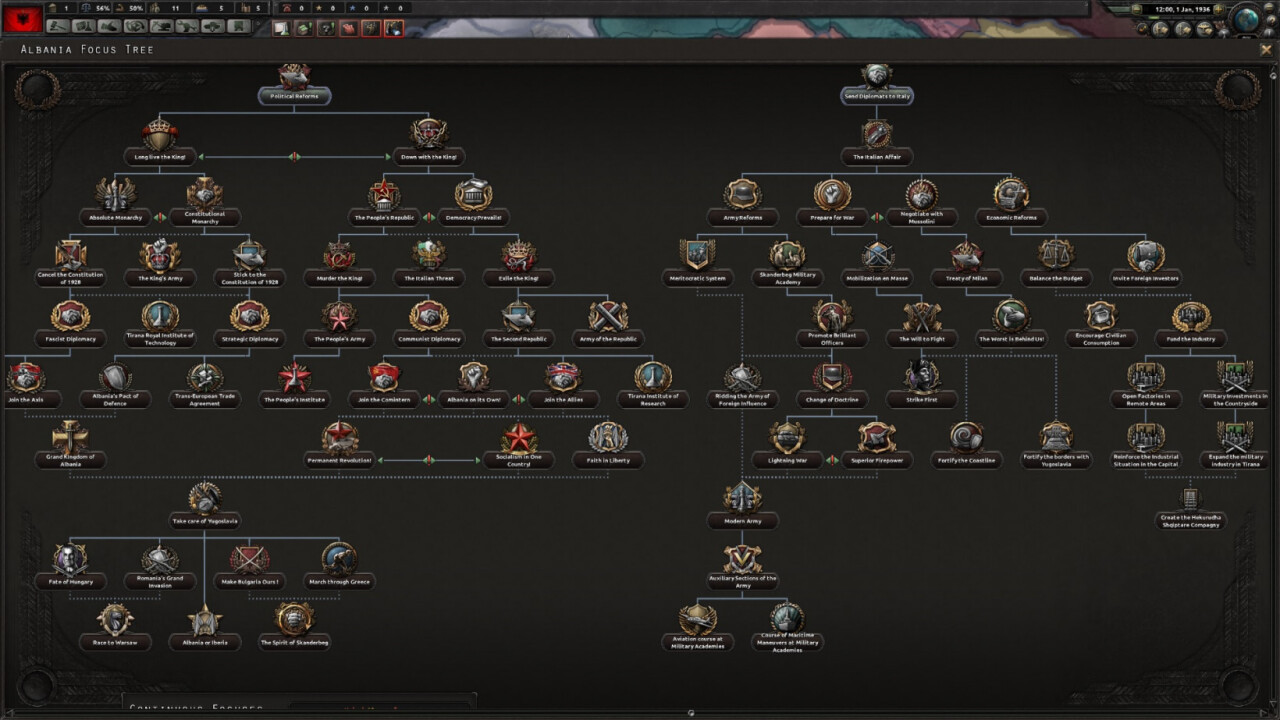

Ah yes, I remember thinking, the Paradox games. Hearts of Iron 4, Stellaris, Europa Universalis 4, and Crusader Kings III. I remembered those titles well. Over the years I’ve installed them or their predecessors and made it halfway through their tutorials a dozen times before noping out and uninstalling them.

It’s not that they’re bad or too hard. The problem is that they seem like they’re going to be a lot of fun, and people really seem to like them, but one glance at the UI and it’s clear I don’t have the time or mental bandwidth to get into them right now. I’ll do it later, when I’m not stressed out.

But, I really needed a win to end the year. So I decided to download them again. And then I tried something radical: I sat still for an hour and paid attention.

[Read: How to get over the intimidation factor and start loving hardcore strategy games]

Now I’m hooked on Crusader Kings III and Surviving The Aftermath, working my way through Hearts of Iron 4 and Europa Universalis 4, and looking forward to the next grand strategy or management challenge. I’m also feeling less stressed, less anxious, and more focused. The question is: Why?

I’ve read dozens of peer-reviewed studies on gaming and mental health and, at the risk of painting with a very broad brush, I can sum it up as: in moderation, they can have a calming effect but they can also hyper stimulate. Some experts worry that feeding our brains false rewards in the form of high-score dopamine spikes is bad, others seem to think solving puzzles and playing games that challenge our mental faculties is a good thing.

There’s no consensus and, to the best of my knowledge, there’s no long-term, peer-reviewed, controlled studies on the efficacy of video games to treat specific mental illnesses or social disorders. Especially not by genre.

But I feel better during and after playing a complex strategy game that uses up all my mental faculties for awhile. When I take the reigns of a dynasty head in CKIII or decide the fate of an entire survivor community in Surviving the Aftermath, I can feel my anxiety loosening and the lingering sense of helplessness start to fade away.

These games excel at giving me a sense of power and control that can seldom be found outside of the grand strategy / grand management genres.

However, as far as I can tell, there’s no real science behind this. Sure, we understand games can effect our mental health. But there’s a lot more discourse on the science behind keeping gamers’ attention spans and microtransactions than there is on, for example, whether or not pretending to be a WWII general in a hardcore management game can help treat impostor syndrome or something like that.

I interviewed several designers who worked with Paradox to see if I could figure out why these games seemed to provide exactly what I needed whenever I experienced feelings of powerlessness.

First up, I spoke with Lasse Liljedahl, CEO of Iceflake Studios. They’re responsible for the excellent Surviving the Aftermath, a game that takes the grand management genre to the apocalypse.

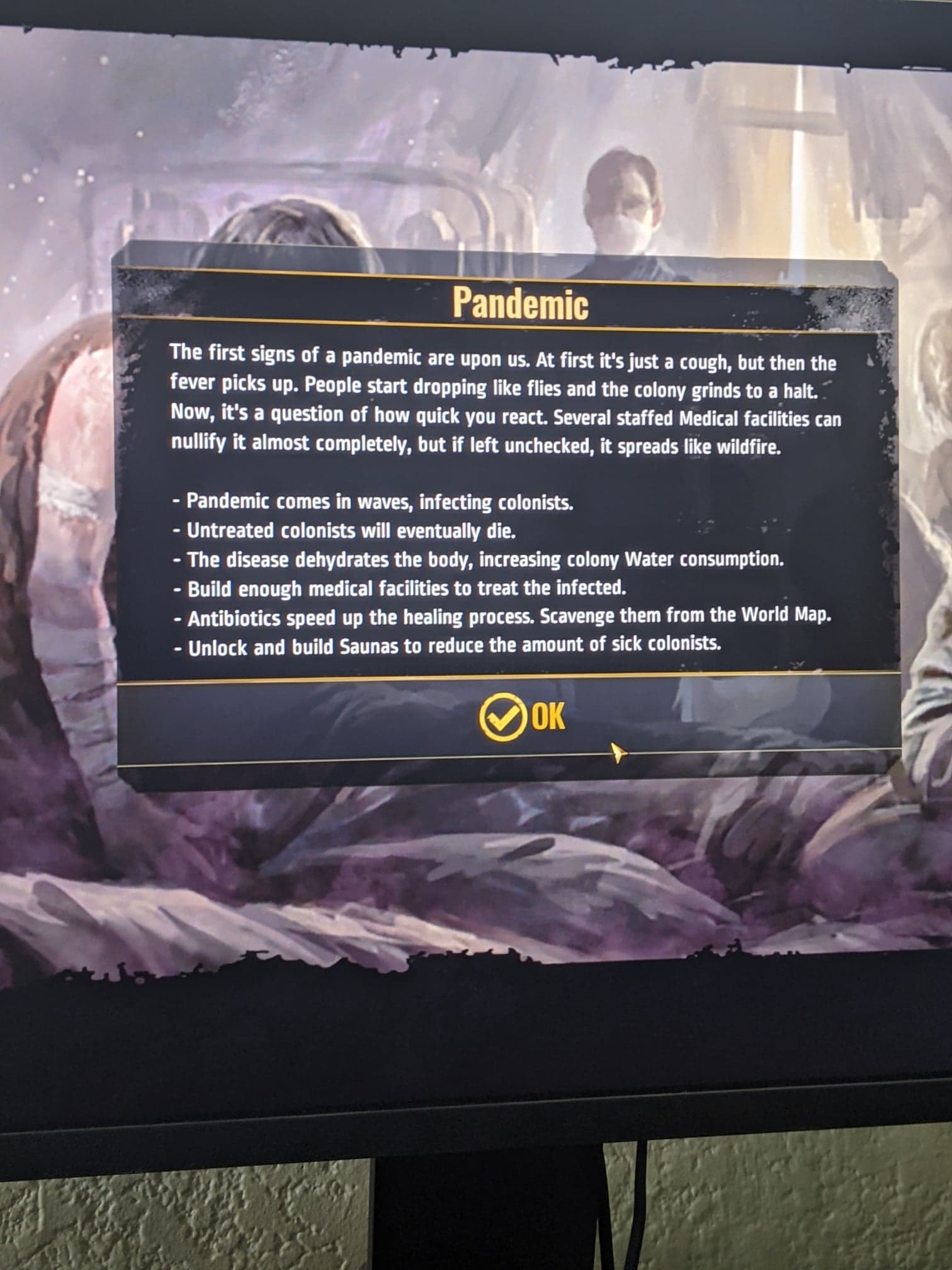

You play Aftermath from the perspective of the entity in charge of an entire settlement. You direct your people, command your heroes, manage supplies, and make hundreds of decisions that each impact the dozens of systems in play at any given time. It gets overwhelming quickly, but you always know exactly what’s going wrong and why.

After explaining my angle, Liljedahl tells me he’s “always thought that games in general were good for mental health.”

At first it feels like a contradiction. Aftermath is a decidedly dark game in that it presupposes humanity is nearly lost and all you can do is try to survive. And the game world is savage – there’s little worth celebrating more than just making it another 24 in-game hours without seeing a premature end-game screen.

But there’s a faint current of hope pulsing beneath the surface in the game. A glimmer of optimism always seems to pull me along in the same way the joy of “winning” a simpler game might give me the old “just one more turn” feeling.

I want to do right by my little people in Aftermath, because it’s something I can actually control. And when I screw up, it’s on me. I can go back, start over, and do things different. I can make it right. I have the power.

According to Liljedahl:

Players expect the game to challenge them. It’s a game you can lose … but you can also feel good about yourself. We wanted to give a little bit more hope, a little more hopeful atmosphere. There’s no night so dark that you can’t see the light at the of the tunnel.

Ultimately, Liljedahl didn’t have any magical insight into the healing powers of his game. He’s just a dedicated designer who builds games for a community known for its loyalty – and for ripping you apart if you put up some weak puzzle-game and call it a grand strategy title.

As Liljedahl told me: “You can’t use as much smoke and mirrors as a story-driven game, for instance.”

So I was able to discern why the games were so hard, and possibly why they’re so satisfying. I was on to something, but I still hadn’t discovered anything ground breaking.

Next I spoke with two of the decision-makers behind Crusader Kings III. The latest dynasty simulator from Paradox is also one of the most well-received grand management games of the modern gaming era. There’s nothing else out there like CKIII.

I spoke with lead game designer Alexander Oltner and content lead designer Maximilian Olbers to find out more about the nuts and bolts behind the game. My reasoning was that if I could learn why they make these games so complex, maybe I could understand why they’ve helped me.

Oltner’s insight instantly clued me in:

Essentially, all of our games are domination fantasies … but when it come to mental health, it’s nothing we look at specifically.

That’s a bit of a bummer, I was secretly hoping to learn they kept a psychologist on staff just to advise about game choices. But, considering there’s no real science on any of this, it makes sense. These games are developed by devoted, talented designers, not psych majors trying to come up with a novel dissertation.

But it was also illuminating when Oltner called them “domination fantasies.” It’s the ability to see myself slowly gaining and then exerting control that draws me in. The opposite of powerlessness is domination.

What’s more interesting, according to Olbers, CKIII in particular is intentionally designed to make you look at “losing” in a different light. According to him:

Losing control in Crusader Kings III just means you have new opportunities.

And that’s where the game shines. You don’t play as a person, you play as a dynasty that persists throughout the generations. If you screw up one leaders’ life there’s always the next one. It’s the ability to try out complicated strategies and the necessity to put in honest mental work towards accomplishing a goal that makes these games feel important. And when you fail, you do so in a sandbox where the only lives that are affected are digital and fictional.

At the end of my quest I realized that science doesn’t always have the answers (yet). I was looking for an explanation into something that, frankly, didn’t require any fancy insights. Grand strategy games are hard, and the harder the challenge – relative to your experience – the more you stand to get out of them.

Next up: war games!

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.