Recently I noticed myself feeling a sort of anxiety whenever I was away from my phone for too long.

I found myself constantly wondering what was happening without me (or to me) online and became aware of just how often I’d pull my phone out of my pocket to “just check the time” only to wind up pointlessly scrolling through Twitter.

It’s a habit we can all relate to, but as I started noticing how it affected friendships, conversations and even my clarity of thought, I decided to do something about it. Most people at this point would probably delete Facebook and Twitter, then write about how great doing that made their life.

I didn’t do that — in reality I need most of those social media profiles for work, and I do enjoy using them occasionally, so I needed to find a better way.

Here’s how I broke the habit.

Stick to the Web

App developers increasingly build their apps to foster addiction and try to build subconscious habits where you constantly find yourself scrolling with little purpose. Increasing the time you spend in an app is the name of the game — and it’s working.

Facebook consistently reports that users are using its services for longer and longer. So does Snapchat. More eyeballs for longer is what every startup is pursuing.

I’ve found an incredibly easy way to beat those odds: use the inferior Web versions. When the app is installed on your phone, distraction is only a tap away, but with the Web there’s a conscious barrier to what you’re doing.

Now my social media browsing is limited to the browser only on mobile. I don’t have Twitter or Facebook installed on my phone; instead, only allowing myself to log in via the Web interface when I really need to catch up. When I’m done, I log out.

This has two major benefits. First, it greatly increases the barrier to entry for aimlessly scrolling through your feed. Using Twitter actually requires visiting Twitter, logging in and then using a crappy version of the site.

For the first few weeks just needing to log in was mostly enough to stop me in my tracks and make me aware of what I was doing: why am I logging back into Facebook?

Second, it kills push notifications. Do I really ever need to know about a mention, like or comment right now? Almost always the answer is no. Occasionally I might miss a direct message, but I try to encourage people to text me next time instead.

This shift has helped me a lot and I now use this method for keeping a lid on mindless phone use for any app I can.

Make your passwords complex — then delete them

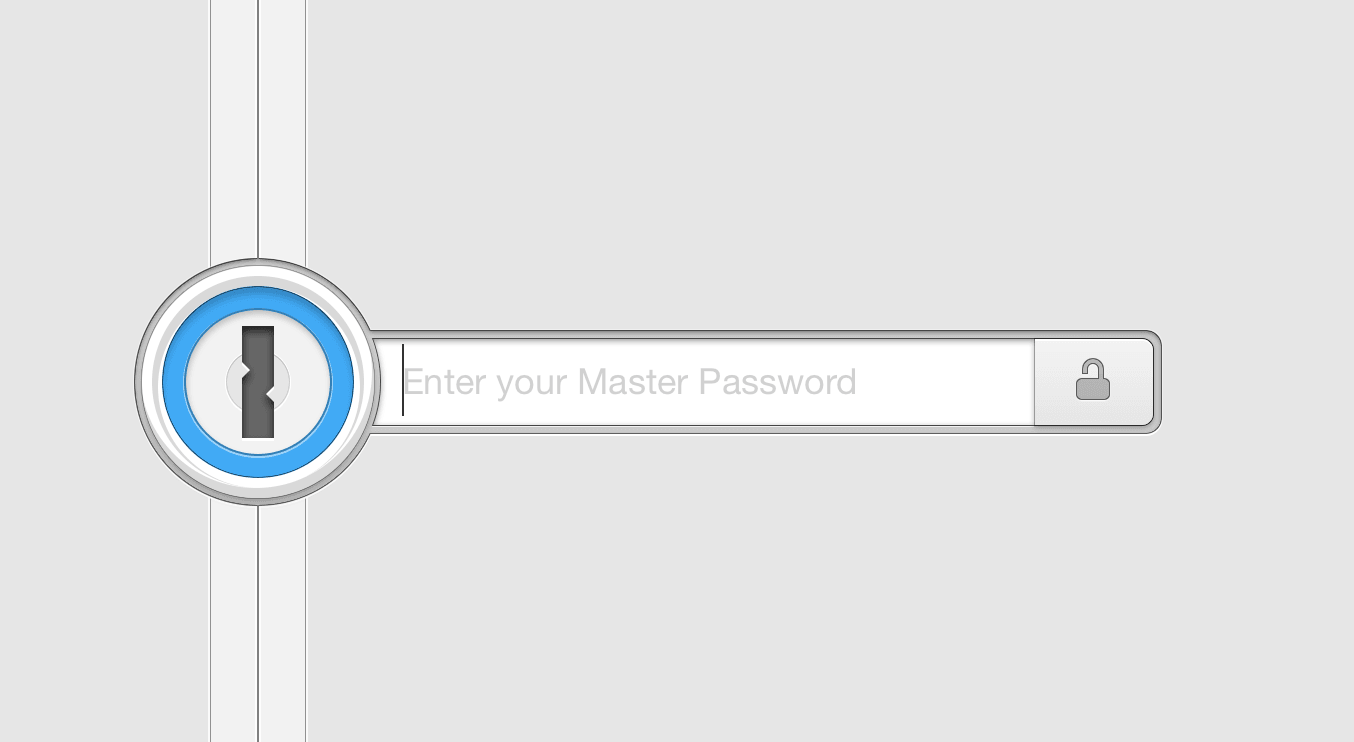

A few weeks in, I noticed a problem. Since I knew the passwords off the top of my head, sometimes having to log in wasn’t enough to break the habit — I’d find myself browsing before I even know what had happened.

I found a way around this too: go into 1Password and generate yourself a 32-character password. Save it, print it, then delete it from your safe. Put it somewhere you can get to it, but don’t carry it with you.

Every time you have to log in, the laborious task of typing in this ridiculous password is a reminder of why you did all this in the first place.

If you can’t kill the app, kill notifications

Notifications are a great form of priming and a trigger for habit building. You see a notification, you slide it to see what’s been sent and you get your reward and rush of endorphins.

Not only do notifications encourage you to lose yourself in a rabbit warren of distraction, they also interrupt your concentration. Some studies estimate the impact of these interruptions to take more than 25 minutes to recover from.

Again, there’s actually a big reason to say no: you just don’t need to know right now. Nobody needs the latest boop from Peach, mention from Twitter, poke from Facebook or snap on Snapchat.

Both iOS and Android do everything they can to encourage you to enable notifications without discretion. Why would you even say no?

Head to your notification settings right now and mercilessly disable things you don’t need to know about. Don’t think about it, just throw the switch — it can always be turned back on.

Over the next week, watch just how much more you’re able to get done and you might be surprised; I find I’m more easily able to read a book, grasp a complex programming problem or simply just focus on a task.

Set up your home screen for success

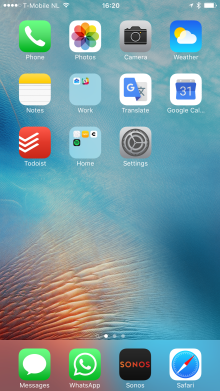

There’ s one more thing you can do to take this to the next level: clear your phone’s home screen of any app that could reinforce that endless scrolling habit.

s one more thing you can do to take this to the next level: clear your phone’s home screen of any app that could reinforce that endless scrolling habit.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t have any interesting apps or games, but they shouldn’t be presented to you every time the phone is unlocked. Just having them visible is enough to make you dive in when you’re still weaning yourself off aimless phone use.

If you’ve deleted your main time-suck apps, you’ll quickly default to something else if it’s made available to you; it doesn’t even matter what it is, because your pointless scrolling doesn’t care!

I was infamously one of those iPhone owners who just had screens full of apps, but now I’ve honed my home screen to only focus on apps that don’t let me lose myself — they only get things done.

Breaking the habit is easy

But you have to create a new one in its place — and commit.

By removing the triggers that reinforce bad habits and introducing new triggers that remind you why you’re stepping back in the first place, you’re far more likely to succeed at reducing distractions.

Using the Web interface of social networks is annoying — people laugh and ask why I don’t use the native app like I’m a luddite — but it’s a powerful way to step back and realize there’s more to life than just staring at your phone.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.