This article originally appeared on the iDoneThis blog.

Ten years ago, Jon Bell, now a designer at Twitter, told his wife that he’d be happy with how much he was making for the rest of his life.

I didn’t make much at the time. But that marked the day I began trying to fight back the impulse for “more” and instead try to discover how “enough” feels.

The conventional wisdom is that to be successful, you have to be really hungry for it, never content with mere sufficiency and outdoing everyone else. Surprisingly, Jon’s philosophy of aiming for enough is a better approach.

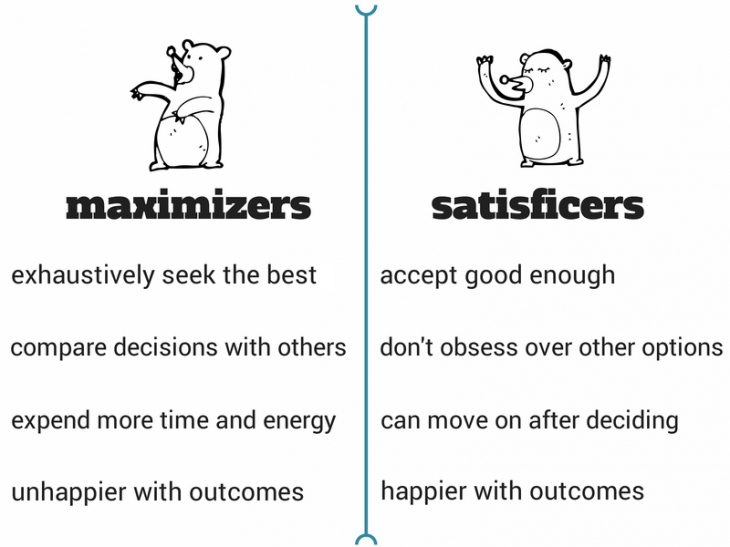

It all comes down to whether you’re a maximizer or a satisficer. A maximizer yearns for perfection — making the best decision after weighing all the choices while a satisficer goes for “good enough.”

This doesn’t mean you have to settle for lower standards — but you do prevent yourself from “trying to maximize every single task outcome and ROI.”

That’s why high achievers fall into the peculiar trap of getting mentally caught up in what you haven’t done — there’s always something else to be working on because it feels like, the more you do, the more you gain an edge. But focusing too hard on maximizing your productivity and choices can come at an ultimate cost to your time, health, and happiness.

Ironically, maximizing doesn’t lead to the optimal result.

Happiness doesn’t come from getting what you want

What made all the difference for the happiness of seniors graduating from college, according to research by Sheena Iyengar, Rachael E. Wells, and Barry Schwartz, was whether they were maximizers or satisficers in choosing their first job out of school.

Overall maximizers were less satisfied, unhappier, and more stressed — despite the fact that they ended up with an average of $7,430 more in salary than the satisficers. They had diligently looked for the very best option, taking into account more external sources of influence including social standards and input from family and peers.

Even after getting their job, maximizers continued to fixate on alternative paths than the one they chose and wished they had pursued even more options.

That dissatisfaction, according to Iyengar, is a consequence of clinging so hard to their goal of finding the very best. She explains:

people who essentially forgot what they wanted in September believed the job they landed was the job they’d always wanted. They were the happy ones. The implication is that so much of happiness comes not from getting what you want, but from wanting what you get.

The problem is that we are not very good at predicting what will make us happy in the future. So holding out for your concept of perfect, long-held goals can backfire.

Satisficing allows you to prioritize

When you’re so busy maximizing your life, it’s easy to lose sight of what’s actually important within it. As researcher Brené Brown discovered in studying the risks of perfectionism:

A lot of people told me that when they put their work away and when they try to be still and be with family, sometimes they feel like they’re coming out of their skins. They’re thinking of everything they’re not doing, and they’re not used to that pace.

Brown concludes: “Healthy striving is about striving for internal goals…. Perfectionism is about what people will think.” That distinction between internal and external striving is key.

Consider how the maximizers in Iyengar’s study, who reached objectively better outcomes from an extrinsic aspect in terms of salary, turned out to be less satisfied. And when University of Rochester psychologists tracked the paths of 147 college graduates, they discovered that people who had intrinsic aspirations such as community involvement, personal growth, and close relationships ended up happier than those with extrinsic aspirations of chasing money, fame, and image.

When you work towards attaining intrinsic aspirations, you’re nourishing basic psychological needs instead of burning through energy comparing options and setting yourself up for disappointment.

The tricky truth is that simply attaining and maximizing for external goals fall short.

If you have maximizer tendencies, strive towards aspirations and motivations that come from within. Adopt the satisficing mindset and like Jon, try to find and be at peace with enough.

You can get started by practicing the 70 percent rule of decision-making, which provides a mental cut-off point to limit time looking and waiting for the best. Instead, you pursue choices that elicit a 70 percent approval rating from you and you can iterate or evolve from there.

As for Jon, satisficing is proving to be the most optimal strategy to thrive and be happy:

The biggest surprise is I haven’t slowed down my creative output, I’ve just re-directed my energy… It’s tremendously freeing and has done wonders for my work. I’ve never been happier, more creative, or more satisfied.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.