Believe it or not, the first emoji was created in 1999 by a Japanese artist, Shigetaka Kurita, who wanted to create a simple, quick, and attractive way of conveying information. At that time, Kurita was working as a developer for i-mode, an internet platform owned by Japan’s main mobile carrier, DOCOMO. Fast-forward almost 20 years and these small, yellow, emotive characters now represent a lot more than at first sight.

Emoji has been referred to as a “lingua franca” — a bridging language that allows us to bypass spoken language barriers and cultural differences. But emoji aren’t just as level ground for communicating, or as an innocent outlet to sext, they’ve become an accessible symbol of activism and politics over this past decade.

“Emoji has become a summary of our society and has increasingly intertwined with our conversations, even when we’re talking about politics,” Lilian Stolk, an emoji expert told TNW. “Not only do we use emoji for politics, but the process of adding new emoji is also a political game. Big tech companies use emoji to show that they represent diversity such as Apple with its disabilities emoji and Google with its gender neutral emoji.”

But, what is a political emoji?

A few months back, when people first started talking about US President ’s potential impeachment on Twitter, the peach emoji — which was once a harmless sexting reference — became the latest protest symbol against , and more specifically, his potential impeachment — get it?

This emoji seemingly became a homonym — having the same spelling or pronunciation but different meanings — after Lizzo, an American singer-songwriter, tweeted a message which gained almost 120,000 likes. Lizzo’s “IMpeachMENT” tweet was likely in celebration of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s decision to launch an impeachment inquiry against Trump.

IM?MENT

— Feelin Good As Hell (@lizzo) September 24, 2019

Emoji are used in their literal sense to spread political messaging, especially in countries were censorship restricts free speech. For example, in China, #MeToo is censored, so people who want to share their stories of sexual harassment and assault instead use the ‘cooked rice’ and ‘rabbit’ emoji because ‘rice bunny’ in China is pronounced similarly to ‘me too.’

Throughout the recent general election campaign in the UK, the red rose emoji was used as a symbol for the Labour party.

Are emojis political now? part 3

Analysis of emojis in the usernames of people who tweet to presidential candidates.

???????⭐

This time I analyzed data from 5000 recent, mixed tweets (popular and recent) until 11/09.Thread below ?#dataviz

— Kairsten Fay ? (@databae_) November 12, 2019

But just as emoji is used to spread positive political messaging, it’s also used to represent the opposite. For example, several emoji including the frog (in reference to Pepe The Frog), the milk glass, and the ‘ok’ sign are used to symbolize ‘white power.’

“The most political thing about emoji that surprised me is that Apple is not displaying the Taiwanese flag on phones in China, and recently they also blocked it on devices in Hong Kong and Macau. This shows that Apple wants to keep the Chinese market a friend,” Stolk added.

“With the more controversial political opinions, I think it’s safer to use an emoji, or a meme, instead of making a message more concrete with words,” Stolk added. “If you bring your political opinion with a layer of irony, you can hide behind the irony. If you post a pepe meme or use the frog emoji people can deny a real connection to extreme right-wing ideas, because it’s ‘just funny.’ But at the same time, it still connects to these ideas.”

The process of adding emoji is a political game

Although it may seem like Emoji just magically appear on our phones once a year, this isn’t exactly how deployment works. The Unicode Consortium, the official body that manage emoji, accept or reject emotive characters submitted by users, designers, and activists.

Over the past couple of years, the Unicode Consortium has faced some backlash over its decisions. Earlier this year, they approved the release of a blood drop emoji in what was widely considered to be a first step in ending period shame and sparking conversations about menstruation.

This is all thanks to a girls-focused development charity, Plan International UK and Plan Australia who in 2017, launched a campaign to create a period emoji in an attempt to reduce the taboo surrounding period and menstrual health.

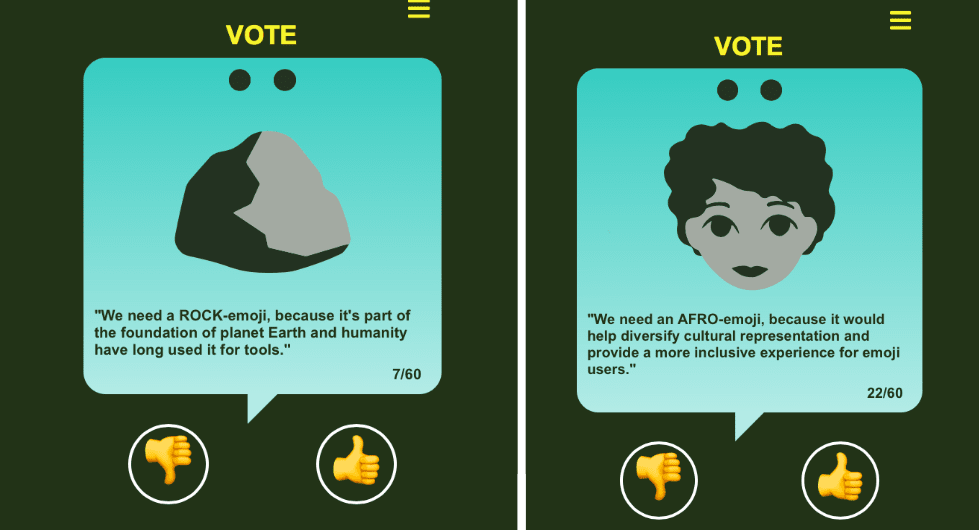

To make the process of adding emoji to our phones more democratic Stolk created, Emoji Voter, a web-based app where people can vote for which emoji should appear on our keyboards.

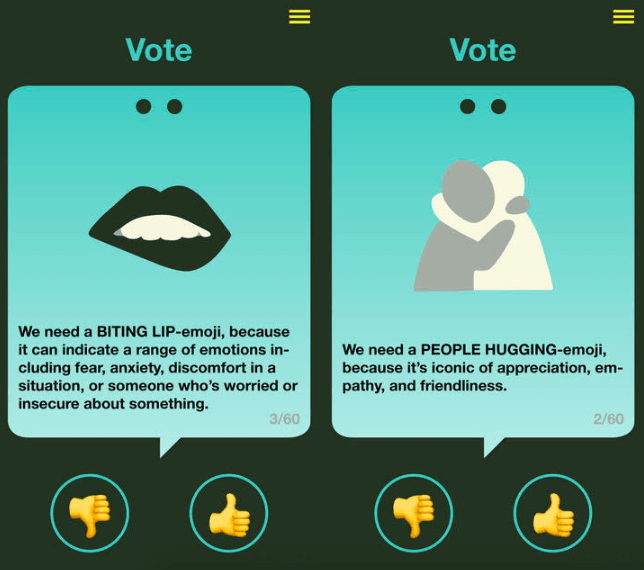

Similarly to Tinder, Emoji Voter works by swiping through various emoji proposals which have been officially received by the Unicode Consortium. By swiping an emoji left, you’re rejecting the design and its meaning, but by swiping right, you agree that this emoji should be included in the next round of updates.

Once the results are in, they’re sent straight to Unicode who then decide if they’ll appear on our phones one day.

“A handful of people from The Unicode Consortium decide which emoji we can communicate with. Imagine if just a few people would decide what words we can use? It’s very weird that we as users don’t have a voice in this. This is what I want to change with Emoji Voter,” Stolk said.

The emoji proposals include harmless, fun examples like a rock to depict Earth’s foundation. But also include more inclusive and political emotive characters like a beaver that’s a ‘playful subcultural symbol among the LGBTQ+ society’ and afro hair which ‘would help diversify cultural representation’ — and it’s currently the only hair-type missing from the emoji catalog.

“As gatekeepers of the language that we all use online, Unicode and their voting members are not consistent in their choices. They state that a new emoji should not be too specific and have the potential to become popular,” Stolk explained. “Then why is there a red-haired emoji and no afro emoji, while there are many more people with an afro worldwide? Why was a period emoji too specific, but there will soon be 70 symbols for people with disabilities? If we continue in this way, within eight years we’ll be scrolling through 5000 emoji. Do we want that? We should think about this better.”

According to Stolk, the most voted emoji will be the hugging and lip biting emoji. “Both are a form of non-verbal communication, and that’s how we use emoji most often,” Stolk said.

Although the voting process is far from perfect, it’s reassuring to see that diversity and inclusivity are increasingly becoming part of the debate. While an emoji may not spark real change in society, it does encourage a conversation and acts as an accessible form of communication between various cultures and languages — it could be argued that emoji speak louder than words.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.